(Prev. : No 16

F/N: 17a, here)

*NB: For those new to UD, FSCO/I means: Functionally Specific Complex Organisation and/or associated Information

From time to time, we need to refocus our attention on foundational issues relating to the positive case for inferring design as best explanation for certain phenomena connected to origins of the cosmos, life and body plans. It is therefore worth the while to excerpt an addition I just made to the IOSE Introduction and Summary page, HT CR, by way of an excerpt from Meyer’s reply to Falk’s hostile review of Signature in the Cell.

In addition, given all too commonly seen basic problems with first principles of right reasoning among objectors to design theory [–> cf. here and here at UD recently . . . ], it will help to add immediately following remarks from the IOSE, on Newton’s four rules of inductive, scientific reasoning, and Avi Sion’s observations on inductive logic.

I trust the below will therefore help to correct many of the widely circulated strawman caricatures of the core reasoning and warrant behind the theory of intelligent design and its pivotal design inference. At least, for those willing to heed duties of care to accuracy, truth, fairness and responsible comment:

________________

>> ID thinker Stephen Meyer argues in his response to a hostile review of his key 2009 Design Theory book, Signature in the Cell:

The central argument of my book is that intelligent design—the activity of a conscious and rational deliberative agent—best explains the origin of the information necessary to produce the first living cell. I argue this because of two things that we know from our uniform and repeated experience, which following Charles Darwin I take to be the basis of all scientific reasoning about the past. First, intelligent agents have demonstrated the capacity to produce large amounts of functionally specified information (especially in a digital form). Second, no undirected chemical process has demonstrated this power. Hence, intelligent design provides the best—most causally adequate—explanation for the origin of the information necessary to produce the first life from simpler non-living chemicals. In other words, intelligent design is the only explanation that cites a cause known to have the capacity to produce the key effect in question . . . . In order to [[scientifically refute this inductive conclusion] Falk would need to show that some undirected material cause has [[empirically] demonstrated the power to produce functional biological information apart from the guidance or activity a designing mind. Neither Falk, nor anyone working in origin-of-life biology, has succeeded in doing this . . . .

The central problem facing origin-of-life researchers is neither the synthesis of pre-biotic building blocks (which Sutherland’s work addresses) or even the synthesis of a self-replicating RNA molecule (the plausibility of which Joyce and Tracey’s work seeks to establish, albeit unsuccessfully . . . [[Meyer gives details in the linked page]). Instead, the fundamental problem is getting the chemical building blocks to arrange themselves into the large information-bearing molecules (whether DNA or RNA) . . . .

For nearly sixty years origin-of-life researchers have attempted to use pre-biotic simulation experiments to find a plausible pathway by which life might have arisen from simpler non-living chemicals, thereby providing support for chemical evolutionary theory. While these experiments have occasionally yielded interesting insights about the conditions under which certain reactions will or won’t produce the various small molecule constituents of larger bio-macromolecules, they have shed no light on how the information in these larger macromolecules (particularly in DNA and RNA) could have arisen. Nor should this be surprising in light of what we have long known about the chemical structure of DNA and RNA. As I show in Signature in the Cell, the chemical structures of DNA and RNA allow them to store information precisely because chemical affinities between their smaller molecular subunits do not determine the specific arrangements of the bases in the DNA and RNA molecules. Instead, the same type of chemical bond (an N-glycosidic bond) forms between the backbone and each one of the four bases, allowing any one of the bases to attach at any site along the backbone, in turn allowing an innumerable variety of different sequences. This chemical indeterminacy is precisely what permits DNA and RNA to function as information carriers. It also dooms attempts to account for the origin of the information—the precise sequencing of the bases—in these molecules as the result of deterministic chemical interactions . . . .

[[W]e now have a wealth of experience showing that what I call specified or functional information (especially if encoded in digital form) does not arise from purely physical or chemical antecedents [[–> i.e. by blind, undirected forces of chance and necessity]. Indeed, the ribozyme engineering and pre-biotic simulation experiments that Professor Falk commends to my attention actually lend additional inductive support to this generalization. On the other hand, we do know of a cause—a type of cause—that has demonstrated the power to produce functionally-specified information. That cause is intelligence or conscious rational deliberation. As the pioneering information theorist Henry Quastler once observed, “the creation of information is habitually associated with conscious activity.” And, of course, he was right. Whenever we find information—whether embedded in a radio signal, carved in a stone monument, written in a book or etched on a magnetic disc—and we trace it back to its source, invariably we come to mind, not merely a material process. Thus, the discovery of functionally specified, digitally encoded information along the spine of DNA, provides compelling positive evidence of the activity of a prior designing intelligence. This conclusion is not based upon what we don’t know. It is based upon what we do know from our uniform experience about the cause and effect structure of the world—specifically, what we know about what does, and does not, have the power to produce large amounts of specified information . . . .

[[In conclusion,] it needs to be noted that the [[now commonly asserted and imposed limiting rule on scientific knowledge, the] principle of methodological naturalism [[ that scientific explanations may only infer to “natural[[istic] causes”] is an arbitrary philosophical assumption, not a principle that can be established or justified by scientific observation itself. Others of us, having long ago seen the pattern in pre-biotic simulation experiments, to say nothing of the clear testimony of thousands of years of human experience, have decided to move on. We see in the information-rich structure of life a clear indicator of intelligent activity and have begun to investigate living systems accordingly. If, by Professor Falk’s definition, that makes us philosophers rather than scientists, then so be it. But I suspect that the shoe is now, instead, firmly on the other foot. [[Meyer, Stephen C: Response to Darrel Falk’s Review of Signature in the Cell, SITC web site, 2009. (Emphases and parentheses added.)]

Thus, in the context of a pivotal example — the functionally specific, complex information stored in the well-known genetic code — we see laid out the inductive logic and empirical basis for design theory as a legitimate (albeit obviously controversial) scientific investigation and conclusion.

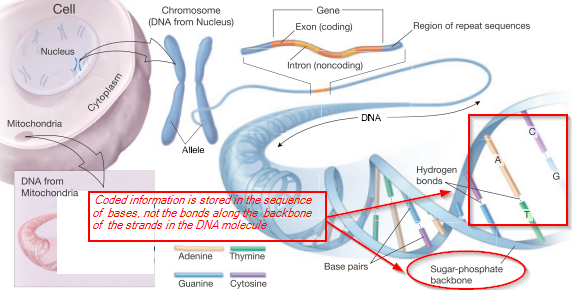

It is worth the pause to (courtesy the US NIH) lay out a diagram of what is at stake here:

In this context — to understand the kind of scientific reasoning involved and its history, it is also worth pausing to excerpt Newton’s Rules of [[Inductive] Reasoning in [[Natural] Philosophy which he used to introduce the Universal Law of Gravitation. In turn, this — then controversial (action at a distance? why? . . . ) — law was in effect generalised from the falling of apples on Earth and the deduced rule that also explained the orbital force of the Moon, and thence Kepler’s mathematically stated empirical laws of planetary motion. So, Newton needed to render plausible how he projected universality:

Rule I [[–> adequacy and simplicity]

We are to admit no more causes of natural things than such as are both true [[–> it is probably best to take this liberally as meaning “potentially and plausibly true”] and sufficient to explain their appearances.

To this purpose the philosophers say that Nature does nothing in vain, and more is in vain when less will serve; for Nature is pleased with simplicity, and affects not the pomp of superfluous causes.

Rule II [[–> uniformity of causes: “like forces cause like effects”]

Therefore to the same natural effects we must, as far as possible, assign the same causes.

As to respiration in a man and in a beast; the descent of stones in Europe and in America; the light of our culinary fire and of the sun; the reflection of light in the earth, and in the planets.

Rule III [[–> confident universality]

The qualities of bodies, which admit neither intensification nor remission of degrees, and which are found to belong to all bodies within the reach of our experiments, are to be esteemed the universal qualities of all bodies whatsoever.

For since the qualities of bodies are only known to us by experiments, we are to hold for universal all such as universally agree with experiments; and such as are not liable to diminution can never be quite taken away. We are certainly not to relinquish the evidence of experiments for the sake of dreams and vain fictions of our own devising; nor are we to recede from the analogy of Nature, which is wont to be simple, and always consonant to [398/399] itself . . . .

Rule IV [[–> provisionality and primacy of induction]

In experimental philosophy we are to look upon propositions inferred by general induction from phenomena as accurately or very nearly true, notwithstanding any contrary hypotheses that may be imagined, till such time as other phenomena occur, by which they may either be made more accurate, or liable to exceptions.

This rule we must follow, that the arguments of induction may not be evaded by [[speculative] hypotheses.

In effect Newton advocated for provisional, empirically tested, reliable and adequate inductive principles resting on “simple” summaries or explanatory constructs. These were to be as accurate to reality as we experience it, as we can get it, i.e. a scientific theory seeks to be true to our world, provisional though it must be. They rest on induction from patterns of observed phenomena and through Rule II — on “like causes like” — were to be confidently projected to cases where we do not observe directly, subject to correction on further observations, not impositions of speculative metaphysical notions.

Since inductive reasoning that leads to provisionally inferred general patterns itself is now being deemed suspect in some quarters, it may help to note as follows from Avi Sion, on what he descriptively calls the principle of universality:

We might . . . ask – can there be a world without any ‘uniformities’? A world of universal difference, with no two things the same in any respect whatever is unthinkable. Why? Because to so characterize the world would itself be an appeal to uniformity. A uniformly non-uniform world is a contradiction in terms.

Therefore, we must admit some uniformity to exist in the world.

The world need not be uniform throughout, for the principle of uniformity to apply. It suffices that some uniformity occurs.

Given this degree of uniformity, however small, we logically can and must talk about generalization and particularization. There happens to be some ‘uniformities’; therefore, we have to take them into consideration in our construction of knowledge. The principle of uniformity is thus not a wacky notion, as Hume seems to imply . . . .

The uniformity principle is not a generalization of generalization; it is not a statement guilty of circularity, as some critics contend. So what is it? Simply this: when we come upon some uniformity in our experience or thought, we may readily assume that uniformity to continue onward until and unless we find some evidence or reason that sets a limit to it. Why? Because in such case the assumption of uniformity already has a basis, whereas the contrary assumption of difference has not or not yet been found to have any. The generalization has some justification; whereas the particularization has none at all, it is an arbitrary assertion.

It cannot be argued that we may equally assume the contrary assumption (i.e. the proposed particularization) on the basis that in past events of induction other contrary assumptions have turned out to be true (i.e. for which experiences or reasons have indeed been adduced) – for the simple reason that such a generalization from diverse past inductions is formally excluded by the fact that we know of many cases [[of inferred generalisations; try: “we can make mistakes in inductive generalisation . . . “] that have not been found worthy of particularization to date . . . .

If we follow such sober inductive logic, devoid of irrational acts, we can be confident to have the best available conclusions in the present context of knowledge. We generalize when the facts allow it, and particularize when the facts necessitate it. We do not particularize out of context, or generalize against the evidence or when this would give rise to contradictions . . .[[Logical and Spiritual Reflections, BK I Hume’s Problems with Induction, Ch 2 The principle of induction.]>>

_________________

In short, there is a definite positive case for design, and it pivots on what I have descriptively termed functionally specific complex organisation and associated information (FSCO/I) — and no, the concept is plainly not just an idiosyncratic notion of a no-account bloggist, but has demonstrable roots tracing to OOL researchers such as Wicken, Orgel and Hoyle across the 1970’s and into the early 1980’s; i.e. before design theory surfaced in response to such findings (another strawman bites the dust . . . ) — and its only known causally adequate source.

In addition, that design inference can be summarised in a flowchart of the scientific investigatory procedure, as for instance was discussed as the very first post in the ID Foundations series at UD, over two years ago:

The result of this can also be summarised in a quantitative expression, as has been repeatedly highlighted, here again excerpting IOSE:

xix: Later on (2005), Dembski provided a slightly more complex formula, that we can quote and simplify, showing that it boils down to a “bits from a zone of interest [[in a wider field of possibilities] beyond a reasonable threshold of complexity” metric:

χ = – log2[10^120 ·ϕS(T)·P(T|H)].

–> χ is “chi” and ϕ is “phi”

xx: To simplify and build a more “practical” mathematical model, we note that information theory researchers Shannon and Hartley showed us how to measure information by changing probability into a log measure that allows pieces of information to add up naturally:

Ip = – log p, in bits if the base is 2. That is where the now familiar unit, the bit, comes from. Where we may observe from say — as just one of many examples of a standard result — Principles of Comm Systems, 2nd edn, Taub and Schilling (McGraw Hill, 1986), p. 512, Sect. 13.2:

Let us consider a communication system in which the allowable messages are m1, m2, . . ., with probabilities of occurrence p1, p2, . . . . Of course p1 + p2 + . . . = 1. Let the transmitter select message mk of probability pk; let us further assume that the receiver has correctly identified the message [[–> My nb: i.e. the a posteriori probability in my online discussion here is 1]. Then we shall say, by way of definition of the term information, that the system has communicated an amount of information Ik given by

I_k = (def) log_2 1/p_k (13.2-1)

xxi: So, since 10^120 ~ 2^398, we may “boil down” the Dembski metric using some algebra — i.e. substituting and simplifying the three terms in order — as log(p*q*r) = log(p) + log(q ) + log(r) and log(1/p) = – log (p):

Chi = – log2(2^398 * D2 * p), in bits, and where also D2 = ϕS(T)

Chi = Ip – (398 + K2), where now: log2 (D2 ) = K2That is, chi is a metric of bits from a zone of interest, beyond a threshold of “sufficient complexity to not plausibly be the result of chance,” (398 + K2). So,

(a) since (398 + K2) tends to at most 500 bits on the gamut of our solar system [[our practical universe, for chemical interactions! ( . . . if you want , 1,000 bits would be a limit for the observable cosmos)] and(b) as we can define and introduce a dummy variable for specificity, S, where

(c) S = 1 or 0 according as the observed configuration, E, is on objective analysis specific to a narrow and independently describable zone of interest, T:Chi = Ip*S – 500, in bits beyond a “complex enough” threshold

- NB: If S = 0, this locks us at Chi = – 500; and, if Ip is less than 500 bits, Chi will be negative even if S is positive.

- E.g.: a string of 501 coins tossed at random will have S = 0, but if the coins are arranged to spell out a message in English using the ASCII code [[notice independent specification of a narrow zone of possible configurations, T], Chi will — unsurprisingly — be positive.

- Following the logic of the per aspect necessity vs chance vs design causal factor explanatory filter, the default value of S is 0, i.e. it is assumed that blind chance and/or mechanical necessity are adequate to explain a phenomenon of interest.

- S goes to 1 when we have objective grounds — to be explained case by case — to assign that value.

- That is, we need to justify why we think the observed cases E come from a narrow zone of interest, T, that is independently describable, not just a list of members E1, E2, E3 . . . ; in short, we must have a reasonable criterion that allows us to build or recognise cases Ei from T, without resorting to an arbitrary list.

- A string at random is a list with one member, but if we pick it as a password, it is now a zone with one member. (Where also, a lottery, is a sort of inverse password game where we pay for the privilege; and where the complexity has to be carefully managed to make it winnable. )

- An obvious example of such a zone T, is code symbol strings of a given length that work in a programme or communicate meaningful statements in a language based on its grammar, vocabulary etc. This paragraph is a case in point, which can be contrasted with typical random strings ( . . . 68gsdesnmyw . . . ) or repetitive ones ( . . . ftftftft . . . ); where we can also see by this case how such a case can enfold random and repetitive sub-strings.

- Arguably — and of course this is hotly disputed — DNA protein and regulatory codes are another. Design theorists argue that the only observed adequate cause for such is a process of intelligently directed configuration, i.e. of design, so we are justified in taking such a case as a reliable sign of such a cause having been at work. (Thus, the sign then counts as evidence pointing to a perhaps otherwise unknown designer having been at work.)

- So also, to overthrow the design inference, a valid counter example would be needed, a case where blind mechanical necessity and/or blind chance produces such functionally specific, complex information. (Points xiv – xvi above outline why that will be hard indeed to come up with. There are literally billions of cases where FSCI is observed to come from design.)

xxii: So, we have some reason to suggest that if something, E, is based on specific information describable in a way that does not just quote E and requires at least 500 specific bits to store the specific information, then the most reasonable explanation for the cause of E is that it was designed. The metric may be directly applied to biological cases:

Using Durston’s Fits values — functionally specific bits — from his Table 1, to quantify I, so also accepting functionality on specific sequences as showing specificity giving S = 1, we may apply the simplified Chi_500 metric of bits beyond the threshold:

RecA: 242 AA, 832 fits, Chi: 332 bits beyondSecY: 342 AA, 688 fits, Chi: 188 bits beyondCorona S2: 445 AA, 1285 fits, Chi: 785 bits beyond

xxiii: And, this raises the controversial question that biological examples such as DNA — which in a living cell is much more complex than 500 bits — may be designed to carry out particular functions in the cell and the wider organism.

So, there is no good reason to pretend that there is no positive or cogent case that has been advanced for design theory, or that FSCO/I — however summarised — is not a key aspect of such a case, or that there is no proper way to quantify the case or express it as an operational scientific procedure.

And of course, lurking in the background is the now over six months old unanswered 6,000 word free- kick- at- goal Darwinist essay challenge on OOL and origin of major body plans.

However, with these now in play, let us hope (against all signs from the habitual patterns we have seen) that a more positive discussion on the merits can now ensue. END