|

|

PZ Myers is incensed at the publication of a Bible tract by Ray Comfort, who argues that it’s just as absurd to believe that the human body evolved by chance as it is to believe that chance processes could generate a can of Coke, such as the one pictured above (public domain image, courtesy of Wikipedia). Over at Pharyngula, Myers wastes no time in demolishing this argument:

The thing is, we know how coke cans (and bible tracts) are made: these are objects that are constructed by human beings. They do not have an independent capability to replicate.

We also know that that is not how biological organisms are made. If we see something like, say, a rabbit, we know and have evidence for the fact that … it doesn’t even require any kind of external agency to make copies of rabbits: just put two of them together and wait….

Furthermore, we know that rabbit replication is imperfect, and that reproduction produces variants. These variants are naturally selected in their environment, and … the properties of the population as a whole gradually change over time…

…[Y]ou’d have to be a fool or have an ulterior motive … to try and imply that aluminum cans and rabbits have to be built by similar designed mechanisms.

In a nutshell: rabbits reproduce, and Coke cans can’t. Additionally, rabbit reproduction generates random variation, which is culled by natural selection, thereby enabling rabbits (but not Coke cans) to evolve. QED.

Now, most readers know that I accept the common descent of living things (unlike Ray Comfort, who is a creationist). However, I would agree with Comfort on one vital point, which Professor Myers appears to have overlooked in his article. You haven’t really explained the appearance of rabbits until you’ve explained the appearance of the very first living organism, from which they are descended. And to do that, you need a theory of abiogenesis: that is, you need to explain how life arose from non-living matter.

Funny, that point sounds very familiar … where have I heard it before? Oh, that’s right. PZ Myers made the very same point himself, back in 2008, in a post titled, 15 misconceptions about evolution. Here’s what he had to say:

I know many people like to recite the mantra that “abiogenesis is not evolution,” but it’s a cop-out. Evolution is about a plurality of natural mechanisms that generate diversity. It includes molecular biases towards certain solutions and chance events that set up potential change as well as selection that refines existing variation. Abiogenesis research proposes similar principles that led to early chemical evolution. Tossing that work into a special-case ghetto that exempts you from explaining it is cheating, and ignores the fact that life is chemistry. That creationists don’t understand that either is not a reason for us to avoid it.

Except that there’s one little problem: scientists haven’t a clue how life evolved. Don’t take my word for it: ask Professor James M. Tour, a synthetic organic chemist, specializing in nanotechnology, who is also is the T. T. and W. F. Chao Professor of Chemistry, Professor of Materials Science and NanoEngineering, and Professor of Computer Science at Rice University in Houston, Texas. In addition to holding more than 120 United States patents, as well as many non-US patents, Professor Tour has authored more than 600 research publications. He was inducted into the National Academy of Inventors in 2015, and he was named among “The 50 most Influential Scientists in the World Today” by TheBestSchools.org in 2014. Tour was named “Scientist of the Year” by R&D Magazine in 2013, and he won the ACS Nano Lectureship Award from the American Chemical Society in 2012. As if that were not enough, Tour was ranked one of the top 10 chemists in the world over the past decade by Thomson Reuters in 2009. Clearly, the man knows what he’s talking about.

Earlier this year, Professor Tour gave a talk titled, The Origin of Life – An Inside Story, which I blogged about here. Professor Tour did not attempt to demonstrate the impossibility of abiogenesis as a scientific theory, in his talk. Rather, his aim was more modest: to show that the Emperor has no clothes, and that current theories about how life might have evolved are mere speculation, unsupported by a shred of evidence. The take-home message of his talk was that currently, scientists know nothing about how the ingredients of life originated, let alone life itself. For the past sixty years, scientists have been “telling lies for Darwin” (to adapt a phrase coined by Ian Plimer) and presenting the problem of life’s origin as a work in progress, when in reality, the progress made to date by scientists in the field is virtually zero.

Professor Tour was refreshingly candid about how little scientists know, not only about the origin of life, but also about the origin of the basic building blocks of life. In his own words:

We have no idea how the molecules that compose living systems could have been devised such that they would work in concert to fulfill biology’s functions. We have no idea how the basic set of molecules, carbohydrates, nucleic acids, lipids and proteins, were made and how they could have coupled in proper sequences, and then transformed into the ordered assemblies until there was the construction of a complex system, and eventually to that first cell. Nobody has any idea on how this was done when using our commonly understood mechanisms of chemical science. Those who say that they understand are generally wholly uninformed regarding chemical synthesis.

From a synthetic chemical perspective, neither I nor any of my colleagues can fathom a prebiotic molecular route to construction of a complex system. We cannot even figure out the prebiotic routes to the basic building blocks of life: carbohydrates, nucleic acids, lipids and proteins. Chemists are collectively bewildered. Hence I say that no chemist understands prebiotic synthesis of the requisite building blocks, let alone assembly into a complex system.

That’s how clueless we are. I’ve asked all of my colleagues: National Academy members, Nobel Prize winners. I sit with them in offices. Nobody understands this. So if your professor says, “It’s all worked out,” [or] your teachers say, “It’s all worked out,” they don’t know what they’re talking about. It is not worked out.

In his talk, Professor Tour decided to focus on the origin of just one of the four basic building blocks of life: carbohydrates. He then proceeded to list eleven enormous hurdles faced by any blind, unguided process, in generating these compounds, and concluded:

Therefore, small changes in ultimate functioning require major rerouting in the synthetic approaches. All changes, when doing chemistry, are hard and cannot be done by the usual hand-waving arguments or simple erasures on a board. Laborious and intentional elements of forethought are required…

How could this have happened in prebiotic chemistry? How do you go from a starting material to a product that’s a complex product? What we do is we work our way back slowly. But Nature doesn’t know what its product is going to be at the end! It doesn’t know! It’s just blindly going along.

Near the end of his lecture, Professor Tour administered the final coup de grace in his expose of current scientific theories regarding abiogenesis. It turns out that even if you could get all the ingredients of life together, at a high level of purity, and store them over long periods, they can’t assemble without enzymes:

Let us assume that all the building blocks of life, not just their precursors, could be made in high degrees of purity, including homochirality where applicable, for all the carbohydrates, all the amino acids, all the nucleic acids and all the lipids. And let us further assume that they are comfortably stored in cool caves, away from sunlight, and away from oxygen, so as to be stable against environmental degradation. And let us further assume that they all existed in one corner of the earth, and not separated by thousands of kilometers or on different planets. And that they all existed not just in the same square kilometer, but in neighboring pools where they can conveniently and selectively mix with each other as needed.

Now what? How do they assemble? Without enzymes, the mechanisms do not exist for their assembly. It will not happen and there is no synthetic chemist that would claim differently because to do so would take enormous stretches of conjecturing beyond any that is realized in the field of chemical sciences…

I just saw a presentation by a Nobel prize winner modeling the action of enzymes, and I walked up to him afterward, and I said to him, “I’m writing an article entitled: ‘Abiogenesis: Nightmare.’ Where do these enzymes come from? Since these things are synthesized, … starting from the beginning, where did these things come from?” He says, “What did you write in your article?” I said, “I said, ‘It’s a mystery.’” He said, “That’s exactly what it is: it’s a mystery.”

Readers who wish to view Professor Tour’s talk may do so here:

God of the gaps?

Now, at this point, PZ Myers might interject: “Aha! You’re appealing to the argument from ignorance! That’s God-of-the-gaps reasoning. Just because we don’t know how life originated, doesn’t mean we’ll never know. And given the track record of science in solving mysteries, it’s a pretty good bet that we will one day resolve this problem. So there!”

I would reply that science generates new mysteries as fast as it resolves old ones, so the notion that the list of unsolved scientific problems is shrinking is a triumphalistic myth. (Dark energy, dark matter, and the problem of reconciling quantum gravity with general relativity are just a few examples that spring to mind of problems that have arisen within the past few decades.) The origin of life is a new mystery – and a particularly intractable one at that. Thinkers like Aristotle and Aquinas took spontaneous generation for granted: for them, it wasn’t a mystery, but an everyday occurrence. They had no idea of the staggering odds against life originating via unguided processes – a subject I have blogged about in my 2014 articles, The dirty dozen: Twelve fallacies evolutionists make when arguing about the origin of life and It’s time for scientists to come clean with the public about evolution and the origin of life.

I should add that Intelligent Design theory makes no claim to be able to scientifically demonstrate that the Designer of life is God, although many (including myself) believe Him to be.

Finally, I’d like to quote a short passage from the highly acclaimed book, Seven Days That Divide the World (Zondervan, Grand Rapids, Michigan, 2011) by John C. Lennox, Professor of Mathematics at the University of Oxford:

That brings us back to the matter of gaps. There would appear to be different kinds of gap, as I have argued in detail elsewhere. Some gaps are gaps of ignorance and are eventually closed by increased scientific knowledge – they are the bad gaps that figure in the expression “God of the gaps.” But there are other gaps, gaps that are revealed by advancing science (good gaps).…

…[T]he nature of life itself militates strongly against there ever being a purely naturalistic theory of life’s origin. There is an immense gulf between the non-living and the living that is a matter of kind, not simply of degree. It is like the gulf between the raw materials paper and ink, on the one hand, and the finished product of paper with writing on it, on the other. Raw materials do not self-organise into linguistic structures. Such structures are not “emergent” phenomena, in the sense that they do not appear without intelligent input.

Any adequate explanation for the existence of the DNA-coded database and for the prodigious information storage and processing capabilities of the living cell must involve a source of information that transcends the basic physical and chemical materials out of which the cell is constructed… Such processors and programmes, on the basis of all we know from computer science, cannot be explained, even in principle, without the involvement of a mind. (2011, pp. 171, 174.)

A thought experiment: Does nearly-perfect replication undercut the inference to design?

|

As we have seen, Professor Myers contends that the reason why we infer design in the case of the Coke can but not in the case of the rabbit is that rabbits reproduce (with minor variations accumulating in lineages over the course of time), whereas Coke cans don’t. But what if astronauts arrived on a strange planet and found robots that looked very much like Coke cans, which were capable of reproducing? And what if reproduction in these robots turned out to be controlled by an internal program that was capable of undergoing variations? Would the astronauts still infer that the robots were designed, and would they still be justified in doing so? I’d be interested to hear readers’ opinions on these questions, and if PZ Myers wants to weigh in, he is of course welcome to do so. For my own part, I think the answer to both questions is yes. If we found such replicating robots, we would be sure of one thing: some intelligent agent designed them.

Here’s the kicker: is it rational to continue to believe that life on Earth arose naturally, if the odds of its having done so are even lower than the odds of a replicating robot having arisen naturally?

How William Paley rebutted the skeptical argument from reproduction, back in 1802

It may interest readers to know that the “reproduction objection” to biological design inferences was anticipated and rebutted over 200 years ago, by the Christian apologist and philosopher William Paley, in his Natural Theology. Paley is popularly known as the author of the “watchmaker argument,” which likens the organs of living things to watches, in order to argue that these organs must have been designed. For Paley, both organs and watches were contrivances, composed of parts working together to perform a function. Contrivances, argued Paley, were invariably the work of an intelligent mind.

Perhaps the silliest myth about William Paley’s Natural Theology is that he overlooked a rather obvious dissimilarity between living things and artifacts: that living things reproduce and are therefore capable of gradually improving or refining their design, whereas artifacts such as watches don’t reproduce, which is why they are utterly incapable of improving their design on a step-by-step basis. The fact is that Paley spent four whole pages refuting this argument in Chapter II of his book, where he imagines what a person would rationally infer, if he found a watch that was capable of making a copy of itself:

Suppose, in the next place, that the person who found the watch, should, after some time, discover that, in addition to all the properties which he had hitherto observed in it, it possessed the unexpected property of producing, in the course of its movement, another watch like itself (the thing is conceivable); that it contained within it a mechanism, a system of parts, a mould for instance, or a complex adjustment of lathes, files, and other tools, evidently and separately calculated for this purpose; let us inquire, what effect ought such a discovery to have upon his former conclusion.

I. The first effect would be to increase his admiration of the contrivance, and his conviction of the consummate skill of the contriver. Whether he regarded the object of the contrivance, the distinct apparatus, the intricate, yet in many parts intelligible mechanism, by which it was carried on, he would perceive, in this new observation, nothing but an additional reason for doing what he had already done, — for referring the construction of the watch to design, and to supreme art. If that construction without this property, or which is the same thing, before this property had been noticed, proved intention and art to have been employed about it; still more strong would the proof appear, when he came to the knowledge of this further property, the crown and perfection of all the rest.

II. He would reflect, that though the watch before him were, in some sense, the maker of the watch, which was fabricated in the course of its movements, yet it was in a very different sense from that, in which a carpenter, for instance, is the maker of a chair; the author of its contrivance, the cause of the relation of its parts to their use. With respect to these, the first watch was no cause at all to the second: in no such sense as this was it the author of the constitution and order, either of the parts which the new watch contained, or of the parts by the aid and instrumentality of which it was produced.…

III. Though it be now no longer probable, that the individual watch, which our observer had found, was made immediately by the hand of an artificer, yet doth not this alteration in anywise affect the inference, that an artificer had been originally employed and concerned in the production. The argument from design remains as it was. Marks of design and contrivance are no more accounted for now, than they were before. In the same thing, we may ask for the cause of different properties. We may ask for the cause of the colour of a body, of its hardness, of its head; and these causes may be all different. We are now asking for the cause of that subserviency to a use, that relation to an end, which we have remarked in the watch before us. No answer is given to this question, by telling us that a preceding watch produced it. There cannot be design without a designer; contrivance without a contriver; order without choice; arrangement, without any thing capable of arranging; subserviency and relation to a purpose, without that which could intend a purpose; means suitable to an end, and executing their office, in accomplishing that end, without the end ever having been contemplated, or the means accommodated to it. Arrangement, disposition of parts, subserviency of means to an end, relation of instruments to a use, imply the presence of intelligence and mind. (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter II, pp. 8-11)

Readers who are curious to learn more about Paley’s argument may be interested to have a look at my 2012 article, Paley’s argument from design: Did Hume refute it, and is it an argument from analogy?

Did Darwin refute Paley’s argument?

|

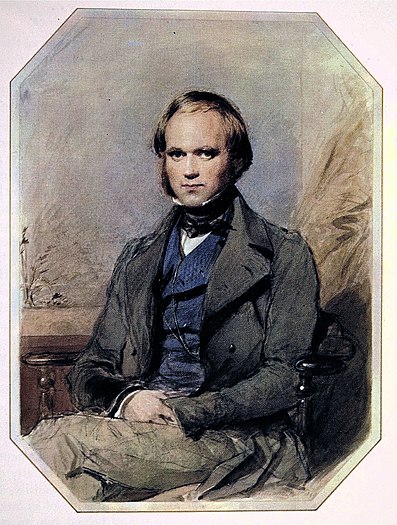

Portrait of Charles Darwin, by George Richmond. Late 1830s. Image courtesy of Richard Leakey, Roger Lewin and Wikipedia.

Modern-day evolutionists often claim that Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species, published in 1859, decisively refuted Paley’s argument for a Designer, once and for all. For my part, I think Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection made a relatively minor dent in Paley’s case.

In a nutshell, Paley’s argument is that intelligent agency is the only process adequate to account for the origin of what he calls contrivances – that is, systems whose parts are intricately arranged and co-ordinated to subserve some common end. (For the purposes of Paley’s argument, it is utterly irrelevant whether this end is intrinsic to the parts in question, as in a living organism, or extrinsic, as in an artifact.) What Charles Darwin did was to put forward a mechanism (natural selection) which is capable (in principle) of explaining how one complex, highly co-ordinated system of parts which assists an organism’s survival could, over millions of years, gradually evolve into another complex system serving an altogether different purpose, through an undirected (“blind”) process. (Of course, such an evolutionary transformation can only occur if there is a viable pathway between the two systems, which blind processes are capable of traversing without any intelligent guidance.) What Darwin did not show, however, is how the fundamental biochemical systems upon which all organisms rely for their survival, could have came into existence, in the first place. We might refer to these fundamental systems in Nature as Paley’s original contrivances. These contrivances cannot be explained away as modifications of pre-existing biological systems, since by definition, anything that preceded them was not viable.

I conclude that in the absence of a Darwinian explanation for the origin of life, Paley’s argument remains perfectly valid, for biochemical systems which are universal to living things, and which go back to the dawn of life on Earth. These “original systems” are “contrivances” in Paley’s sense of the word, and as they were not modified from other systems found in living things, Paley’s argument would still apply to them.

In order to successfully rebut Paley’s argument, then, evolutionists therefore need to explain the emergence of life itself – something which they have so far signally failed to do.

Conclusion

Professor PZ Myers writes that “you’d have to be a fool or have an ulterior motive … to try and imply that aluminum cans and rabbits have to be built by similar designed mechanisms.” While it’s true that rabbits are constructed very differently from cans, the assembly process for a rabbit – or even for the 4 billion-year-old one-celled organism from which it descended – is vastly more complicated than the assembly line process for an aluminium can. To infer design in the latter case, while denying it in the former, strikes me as intellectually obstinate.

What do readers think?