We live in a Kant-haunted age, where the “ugly gulch” between our inner world of appearances and judgements and the world of things in themselves is often seen as unbridgeable. Of course, there are many other streams of thought that lead to widespread relativism and subjectivism, but the ugly gulch concept is in some ways emblematic. Such trends influence many commonly encountered views, most notably our tendency to hold that being a matter of taste, beauty lies solely in the eye of the beholder.

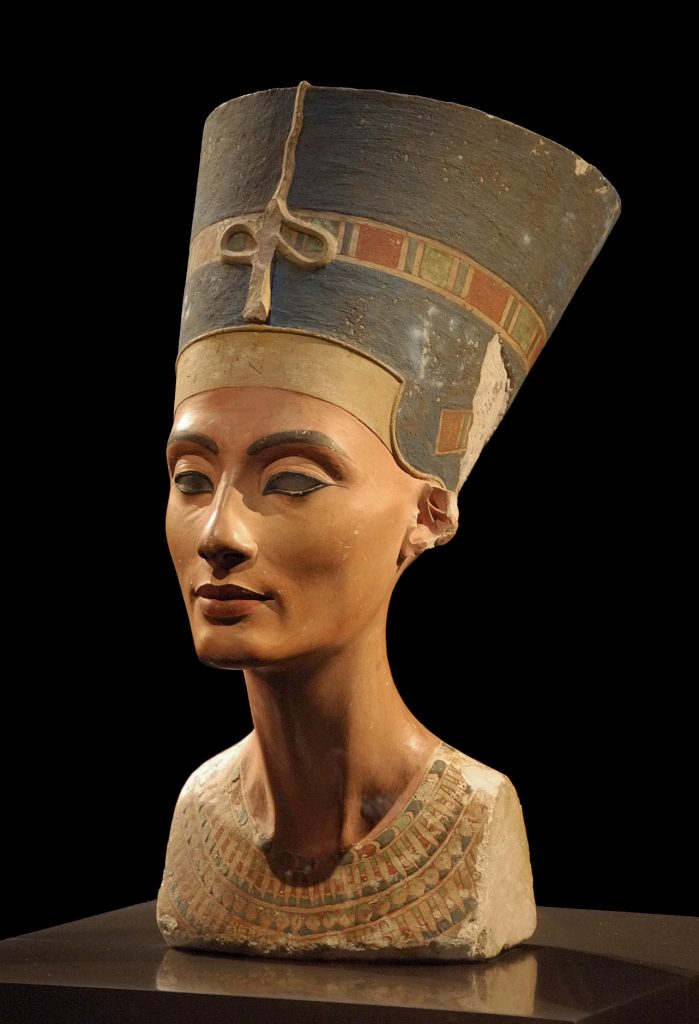

And yet, we find the world-famous bust of Nefertiti:

Compare, 3400 years later; notice the symmetry and focal power of key features for Guinean model, Sira Kante :

Sira Kante

And then, ponder the highly formal architecture of the Taj Mahal:

ADDED: To help drive home the point, here is a collage of current architectural eyesores:

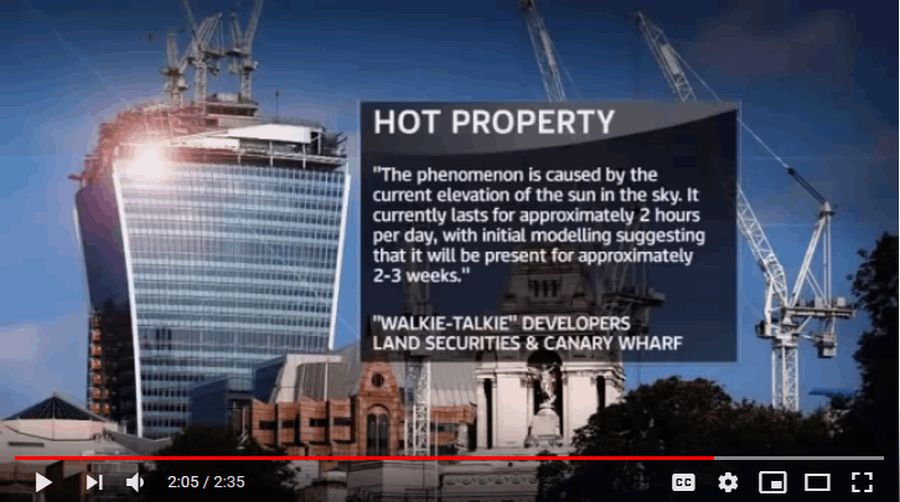

Added, Mar 23 — Vernal Equinox: The oddly shaped building on London’s skyline is called “Walkie-Talkie” and due to its curved surface creates a heating hazard at the height of summer on a nearby street — yet another aspect of sound design that was overlooked (this one, ethical):

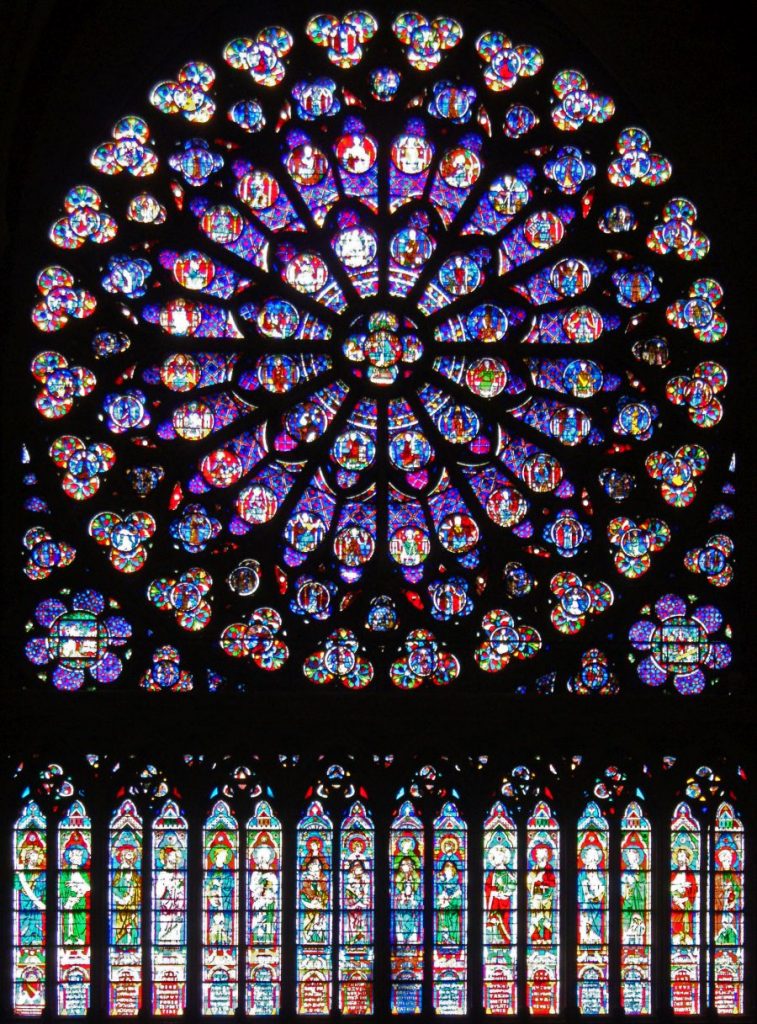

Since it has come up I add the Louvre’s recent addition of a Pyramid (which apparently echoes a similar temporary monument placed there c. 1839 to honour the dead in an 1830 uprising). Notice, below, how symmetric it is in the context of the museum; where triangular elements are a longstanding part of the design as may be seen from the structure below the central dome and above many windows. Observe the balance between overall framework and detailed elements that relieve the boredom of large, flat blank walls. Historically, also, as Notre Dame’s South Rose Window so aptly illustrates, windows and light have been part of the design and function of French architecture. Notice, how it fits the symmetry and is not overwhelmingly large, though of course those who objected that it is not simply aligned with the classical design of the building have a point:

Yet again, the similarly strongly patterned South Rose Window at Notre Dame (with its obvious focal point, as well as how the many portraits give delightful detail and variety amidst the symmetry) :

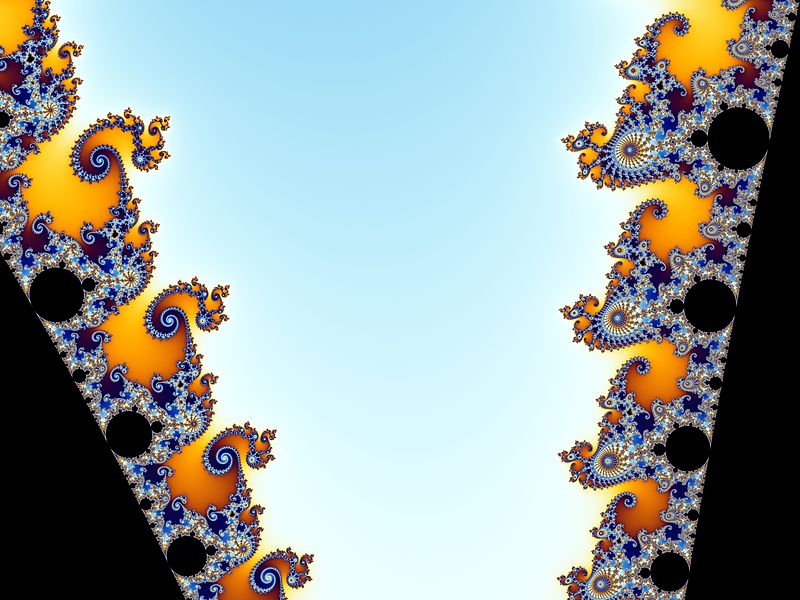

Compare, patterning, variety and focus with subtle asymmetry in part of “Seahorse Valley” for the Mandelbrot set:

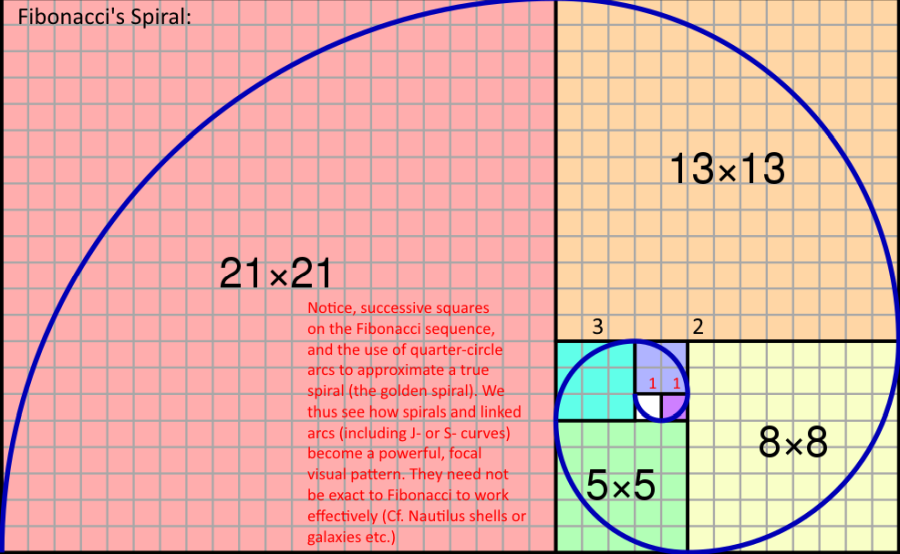

I add, let us pause to see the power of spirals as a pattern, tying in the Fibonacci sequence and thus also the Golden Ratio, Phi, 1.618 . . . (where concentric circles as in the Rose Window, have much of the same almost hypnotic effect and where we see spirals in the seahorse valley also):

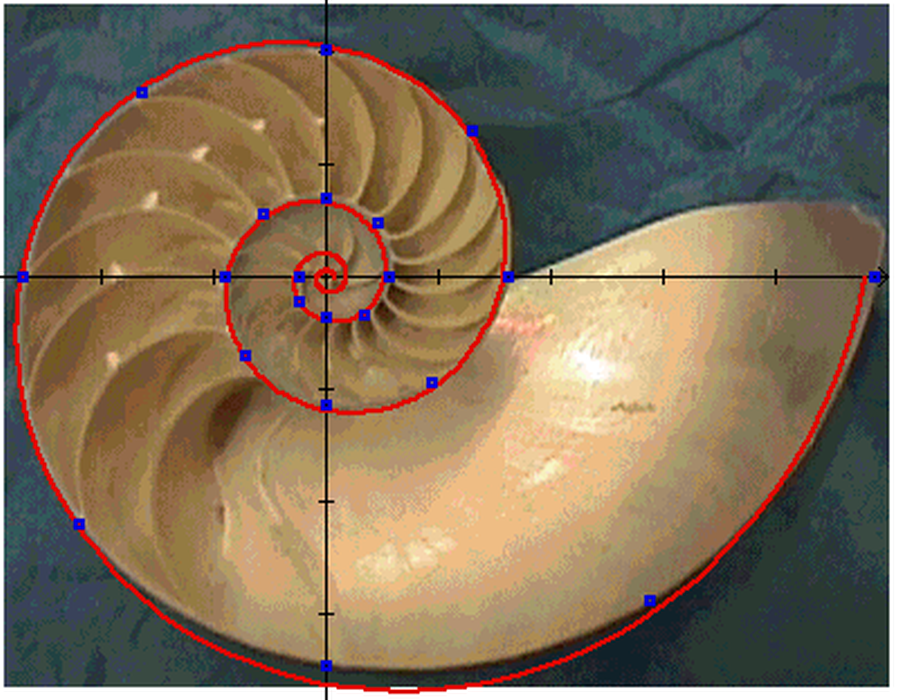

Here, let us observe a least squares fit logarithmic spiral superposed on a cut Nautilus shell:

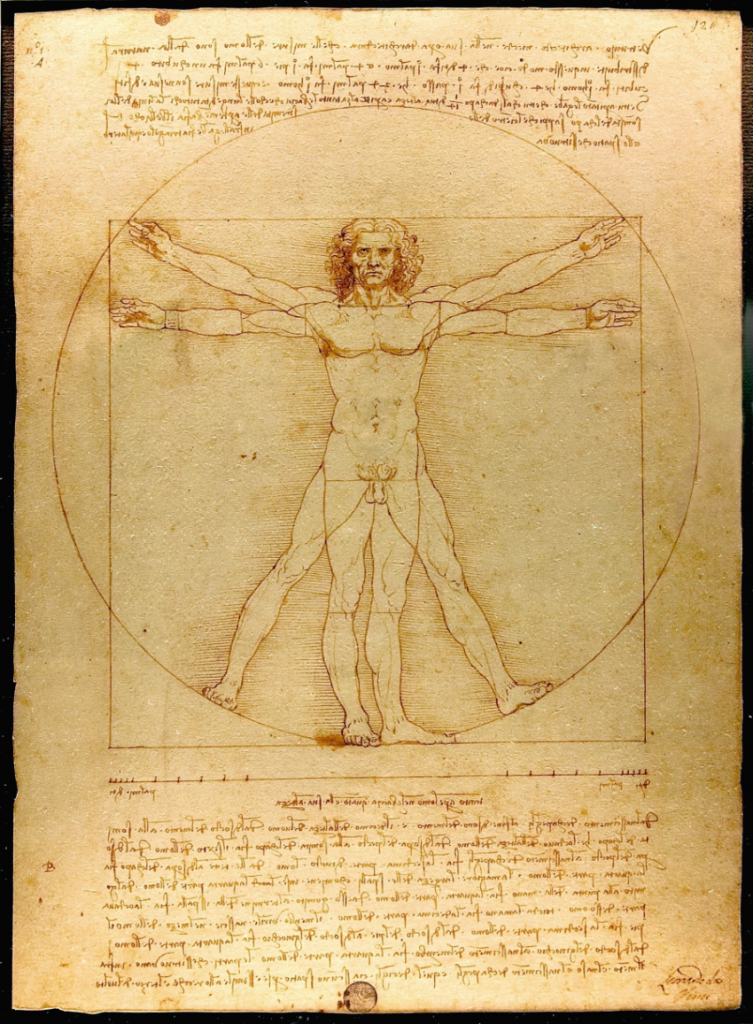

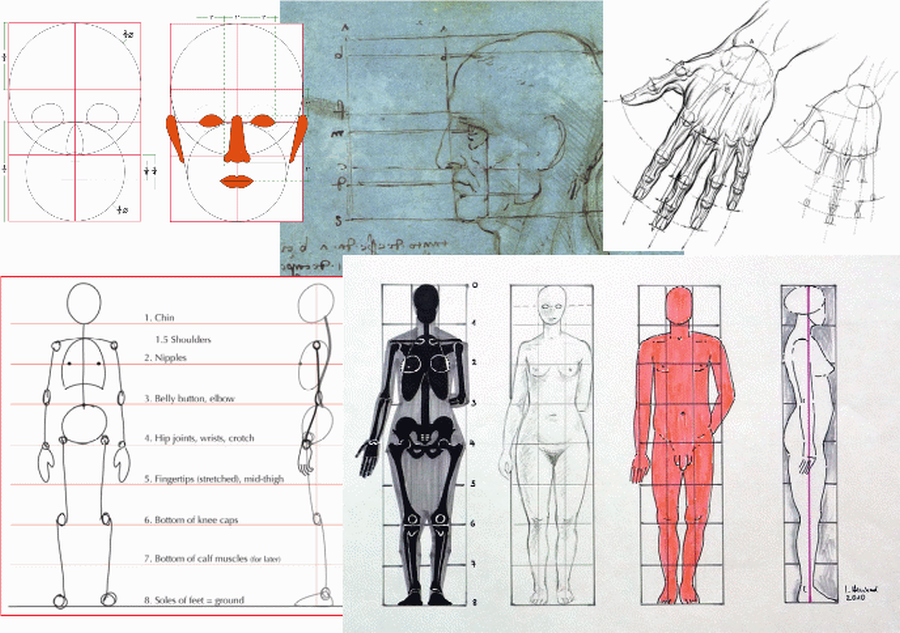

Let us also note, Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, as an illustration of patterns and proportions, noting the impact of the dynamic effect of the many S- and J-curve sculptural forms of the curved shapes in the human figure:

Note, a collage of “typical” human figure proportions:

Contrast the striking abstract forms (echoing and evoking human or animal figures), asymmetric patterning, colour balances, contrasts and fractal-rich cloudy details in the Eagle Nebula:

Also, the fractal patterning and highlighted focus shown by a partially sunlit Grand Canyon:

And then, with refreshed eyes, ponder Mona Lisa, noticing how da Vinci’s composition draws together all the above elements:

Let me also add, in a deliberately reduced scale, a reconstruction of what the portrait may have originally looked like. Over 400 years have passed, varnish has aged and yellowed, poplar wood has responded to its environment, some pigments have lost their colour, there have apparently been over-zealous reconstructions. Of course, the modern painter is not in Da Vinci’s class.

However, such a reconstruction helps us see the story the painting subtly weaves.

A wealthy young lady sits in a three-quarters pose . . . already a subtle asymmetry, in an ornate armchair, on an elevated balcony overlooking a civilisation-tamed landscape; she represents the upper class of the community that has tamed the land. Notice, how a serpentine, S-curved road just below her right shoulder ties her to the landscape and how a ridge line at the base of her neck acts as a secondary horizon and lead in. Also, the main horizon line (at viewer’s eye-level) is a little below her eyes; it is relieved by more ridges. She wears bright red, softened with dark green and translucent layers. Her reddish brown hair is similarly veiled. As a slight double-chin and well-fed hands show, she is not an exemplar of the extreme thinness equals beauty school of thought. The right hand is brought over to the left and superposed, covering her midriff — one almost suspects, she may be an expectant mother. Her eyes (note the restored highlights) look to her left . . . a subtle asymmetry that communicates lifelike movement so verisimilitude, as if she is smiling subtly with the painter or the viewer — this is not a smirk or sneer. And of course the presence of an invited narrative adds to the aesthetic power of the composition.

These classics (old and new alike) serve to show how stable a settled judgement of beauty can be. Which raises a question: what is beauty? Like unto that: are there principles of aesthetic judgement that give a rational framework, setting up objective knowledge of beauty? And, how do beauty, goodness, justice and truth align?

These are notoriously hard questions, probing aesthetics and ethics, the two main branches of axiology, the philosophical study of the valuable.

Where, yes, beauty is recognised to be valuable, even as ethics is clearly tied to moral value and goodness and truth are also valuable, worthy to be prized. It is unsurprising that the Taj Mahal was built as a mausoleum by a King to honour his beautiful, deeply loved wife (who had died in childbirth).

AmHD is a good place to start: beauty is “[a] quality or combination of qualities that gives pleasure to the mind or senses and is often associated with properties such as harmony of form or color, proportion, authenticity, and originality. “

Wikipedia first suggests that beauty is:

a property or characteristic of an animal, idea, object, person or place that provides a perceptual experience of pleasure or satisfaction. Beauty is studied as part of aesthetics, culture, social psychology, philosophy and sociology. An “ideal beauty” is an entity which is admired, or possesses features widely attributed to beauty in a particular culture, for perfection. Ugliness is the opposite of beauty.

The experience of “beauty” often involves an interpretation of some entity as being in balance and harmony with nature, which may lead to feelings of attraction and emotional well-being. Because this can be a subjective experience, it is often said that “beauty is in the eye of the beholder.” However, given the empirical observations of things that are considered beautiful often aligning with the aforementioned nature and health thereof, beauty has been stated to have levels of objectivity as well

It then continues (unsurprisingly) that ” [t]here is also evidence that perceptions of beauty are determined by natural selection; that things, aspects of people and landscapes considered beautiful are typically found in situations likely to give enhanced survival of the perceiving human’s genes.” Thus we find the concepts of unconscious programming and perception driven by blind evolutionary forces. The shadow of the ugly gulch lurks just beneath the surface.

Can these differences be resolved?

At one level, at least since Plato’s dialogue Hippias Major, it has been well known that beauty is notoriously hard to define or specify in terms of readily agreed principles. There definitely is subjectivity, but is there also objectivity? If one says no, why then are there classics?

Further, if no, then why could we lay out a cumulative pattern across time, art-form, nature and theme above that then appears exquisitely fused together in a portrait that just happens to be the most famous, classic portrait in the world?

If so, what are such and can they constitute a coherent framework that could justify the claim to objective knowledge of aesthetic value?

Hard questions, hard as there are no easy, simple readily agreed answers. And yet, the process of addressing a hard puzzle where our intuitions tell us something but it seems to be forever just beyond our grasp, is itself highly instructive. For, we know in part.

Dewitt H. Parker, in opening his 1920 textbook, Principles of Aesthetics, aptly captures the paradox:

Although some feeling for beauty is perhaps universal among men, the

same cannot be said of the understanding of beauty. The average man,

who may exercise considerable taste in personal adornment, in the

decoration of the home, or in the choice of poetry and painting, is

at a loss when called upon to tell what art is or to explain why he

calls one thing “beautiful” and another “ugly.” Even the artist and

the connoisseur, skilled to produce or accurate in judgment, are often

wanting in clear and consistent ideas about their own works or

appreciations. Here, as elsewhere, we meet the contrast between feeling

and doing, on the one hand, and knowing, on the other.

Of course, as we saw above, reflective (and perhaps, aided) observation of case studies can support an inductive process that tries to identify principles and design patterns of effective artistic or natural composition that reliably excite the beauty response. That can be quite suggestive, as we already saw:

- symmetry,

- balance,

- pattern (including rhythms in space and/or time [e.g. percussion, dance]),

- proportion (including the golden ratio phi, 1.618 etc)

- unity or harmony (with tension and resolution), highlighting contrast,

variety and detail, - subtle asymmetry,

- focus or vision or theme,

- verisimilitude (insight that shows/focusses a credible truth/reality)

- echoing of familiar forms (including scaled, fractal self-symmetry),

- skilled combination or composition

- and more.

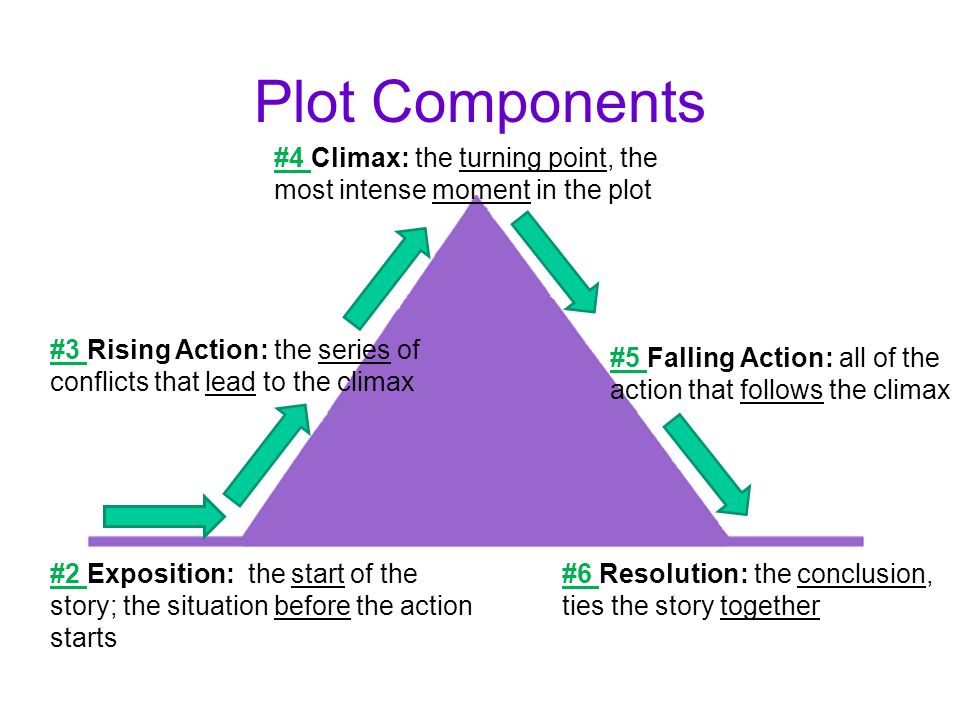

We may see this with greater richness by taking a side-light from literature, drama and cinema, by using the premise that art tells a story, drawing us into a fresh vision of the world, ourselves, possibilities:

Already, it is clear that beauty has in it organising principles and that coherence with variety in composition indicates that there is indeed organisation, which brings to bear purpose and thus a way in for reflective, critical discussion. From this, we reach to development of higher quality of works and growing knowledge that guides skill and intuition without stifling creativity or originality. So, credibly, there is artistic — or even, aesthetic — knowledge that turns on rational principles, which may rightly be deemed truths.

Where, as we are rational, responsible, significantly free , morally governed creatures, the ethical must also intersect.

Where also, art has a visionary, instructive function that can strongly shape a culture. So, nobility, purity and virtue are inextricably entangled with the artistic: the perverse, ill-advised, unjust or corrupting (consider here, pornography or the like, or literature, drama and cinema that teach propaganda or the techniques of vice) are issues to be faced.

And, after our initial journey, we are back home, but in a different way. We may — if we choose — begin to see how beauty, truth, knowledge, goodness and justice may all come together, and how beauty in particular is more than merely subjective taste or culturally induced preference or disguised population survival. Where also, art reflecting rational principles, purposes and value points to artist. END

PS: To document the impact of the beauty of ordinary things (we have got de-sensitised) here are people who thanks to filtering glasses are seeing (enough of) colour for the first time:

Similarly, here are people hearing for the first time:

This will be a bit more controversial, but observe these Korean plastic surgery outcomes: