|

In his latest post, Hart Whacks the ID Movement, Barry Arrington summarizes Orthodox theologian David Bentley Hart’s theological objections to Intelligent Design, and invites readers to respond. The aim of this post of mine is to correct a misunderstanding of Intelligent Design on Dr. Hart’s part, and to show that far from contradicting classical theology, ID complements it in a very useful way.

Let’s begin with a definition. In its broadest sense, the theory of intelligent design (ID) holds that certain empirically observable features of the universe and of living things are best explained by an intelligent cause, and that this intelligent cause can be shown to be the best explanation by applying the scientific method in order to rule out rival explanations, such as chance and/or necessity. (I assume that Dr. Hart is thoroughly familiar with Professor Dembski’s explanatory filter, so I won’t elaborate further.)

How far can intelligent design theory take us?

It has often been said that the theory of intelligent design does not identify the designer. (That, by the way, is why I didn’t capitalize the terms “intelligent design” and “intelligent cause” in the previous paragraph.) But that doesn’t mean that ID can tell us nothing about the designer. If, for instance, it could be shown that certain features of the cosmos-as-a-whole require an intelligent cause, then we would have to conclude that the Intelligent Designer of those features is a supernatural Being beyond space and time, Who is not bound by the laws of Nature. That’s obviously a Deity of some sort.

One obvious objection is that such a Deity might be nothing more than a mere Demiurge, who imposes forms on the cosmos but does not conserve it in existence. But if one could show that the features of the cosmos which indicate a Designer are not merely incidental but essential or defining properties of the cosmos, then it would follow that the cosmos could not exist without those features – in which case, the Designer Who is responsible for those features is also responsible for keeping the cosmos in being. Science can certainly help us discover which properties of a thing are essential properties, and which properties are not. Additionally, the science of cosmology can be defined as the study of the cosmos, considered as a single entity. (That, by the way, is a definition I once got from a Ph.D. student in cosmology, when I happened to asked him to define his research topic.) So it should certainly be possible for us to determine which properties are its defining properties, and scientifically investigate whether these properties show signs of having been designed. An affirmative answer would mean that the Designer doesn’t merely tinker with the cosmos, but rather, gives it its very identity, and makes it what it is. (Let me add in passing that like many Scholastic philosophers, I consider the notion of a “pure passive potency” underlying all forms to be utterly unintelligible: like Suarez, I hold that even prime matter has a form of some sort.) Hence I see no reason in principle why cosmological Intelligent Design could not take us to a Deity Who maintains the world in being, as opposed to a mere Demiurge who does nothing more than impose his designs on a pre-existing cosmos. Of course, the argument for such a Deity would need to be fleshed out in a mathematically and scientifically rigorous fashion, which is something that has yet to be done.

Assuming that Intelligent Design could take us this far, could it ever identify this cosmic Deity with the God of classical theology? I think not. The God of classical theology is metaphysically simple (i.e. devoid of parts of any sort), and since Intelligent Design examines only the physical aspects of Nature, all it could ever hope to establish is that the Designer is a Being with no physical parts. To go any further would be beyond the legitimate scope of Intelligent Design. Similarly, Intelligent Design makes no attempt to address the religious question of whether the Designer is the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, as it lacks the conceptual tools to make such an identification. But by the same token, ID cannot rule out such an identification. Intelligent Design is thus compatible with both classical theology and religious belief, even if it entails neither.

Why the classical arguments for God need supplementation

Now I’d like to address Dr. Hart’s objections to Intelligent Design in detail. In his book, The Experience of God, he argues that classical arguments for the existence of God take universal features of the cosmos as their starting point, unlike ID, which focuses on particulars:

According to the classical arguments, universal rational order – not just this or that particular instance of complexity – is what speaks of the divine mind.

Upon reading this sentence, my first reaction was: why not both? Why can’t we argue for an Intelligent Creator on the basis of both general and particular features of the cosmos?

|

Physicist and cosmologist Sean Carroll, of the California Institute of Technology.

My second reaction was that if Dr. Hart believes that arguments based on “universal rational order” can sway today’s atheists, then he hasn’t argued with them for a long time. In my experience, arguments like this tend to leave them cold. Physicist Sean Carroll (who, by the way, is a very polite atheist) is an excellent case in point. In an essay titled, Does the Universe Need God? (published in The Blackwell Companion to Science and Christianity), he writes:

[T]he ultimate answer to “We need to understand why the universe exists/continues to exist/exhibits regularities/came to be” is essentially “No we don’t.”…

States of affairs only require an explanation if we have some contrary expectation, some reason to be surprised that they hold. Is there any reason to be surprised that the universe exists, continues to exist, or exhibits regularities? When it comes to the universe, we don’t have any broader context in which to develop expectations. As far as we know, it may simply exist and evolve according to the laws of physics. If we knew that it was one element of a large ensemble of universes, we might have reason to think otherwise, but we don’t. (I’m using “universe” here to mean the totality of existence, so what would be called the “multiverse” if that’s what we lived in.)…

There is no reason, within anything we currently understand about the ultimate structure of reality, to think of the existence and persistence and regularity of the universe as things that require external explanation. Indeed, for most scientists, adding on another layer of metaphysical structure in order to purportedly explain these nomological facts is an unnecessary complication.

A reply can certainly be made to the foregoing argument. One could argue, as Dr. Hart does, that “[t]he very notion of nature as a closed system entirely sufficient to itself is plainly one that cannot be verified, deductively or empirically, from within the system of nature.” But Dr. Carroll might reply that if naturalism explains the world more parsimoniously than what he calls “the God hypothesis,” then we may provisionally conclude, as a working hypothesis, that naturalism is true. Carroll also contends – and here, I think, he is on shaky ground – that simpler explanations are inherently more likely to be true, other things being equal. On this logic, then, even if we cannot know that naturalism is true, we might reasonably judge it to be likely, or probable.

An alternative response one might make to Dr. Carroll is that the scientific attempt to explain the features of the cosmos in the most parsimonious and elegant fashion, implicitly assumes that the properties of the cosmos are all descriptive properties, like size and shape. But unless the universe also has some fundamental, built-in prescriptive properties, in addition to the properties we can describe, science becomes an enterprise with no epistemic warrant: in the complete absence of prescriptions, we have no justification for induction. But since the very notion of a prescription presupposes that of an intelligent prescriber, it follows that if the universe does indeed possess prescriptive properties, then there must be a Cosmic Prescriber, and the universe begins to look “nearer to a great thought than to a great machine,” in the words of the great astronomer, Sir James Jeans. (I have argued along these lines previously.)

One could argue in this fashion; but I have yet to see an atheist who was won over by metaphysical arguments of this sort. Such arguments can certainly play a powerful role in confirming people’s belief in God, but by themselves they are usually insufficient to convince people that there is a God. It is an odd but interesting fact that Intelligent Design theory, despite its modesty in theological matters, has helped to persuade quite a few people of the reality of God’s existence. One might ask: why?

A clue can be found in the writings of St. Thomas Aquinas. In his Summa Contra Gentiles Book III, chapter 99, paragraph 9 (That God Can Work Apart From The Order Implanted In Things, By Producing Effects Without Proximate Causes), he declares:

[D]ivine power can sometimes produce an effect, without prejudice to its providence, apart from the order implanted in natural things by God. In fact, He does this at times to manifest His power. For it can be manifested in no better way, that the whole of nature is subject to the divine will, than by the fact that sometimes He does something outside the order of nature. Indeed, this makes it evident that the order of things has proceeded from Him, not by natural necessity, but by free will.

Here, Aquinas says that God’s power and voluntary agency “can be manifested in no better way … than by the fact that He sometimes does something outside the order of nature.” I conclude that he would have had no qualms whatsoever about appealing to effects that require a supernatural Cause, in order to convince skeptics of God’s existence. The question which then arises is: are there any scientifically observable occurrences within the natural world, which point to its having a supernatural Cause?

1. Answering Dr. Hart’s criticisms of cosmological Intelligent Design

It is Dr. Hart’s conviction that neither the biological nor the cosmological versions of Intelligent Design can yield an affirmative answer to this question. To begin with, I’d like to examine what Dr. Hart has to say about cosmological ID:

…[T]hose who argue for the existence of God principally from some feature or other of apparent cosmic design… have not advanced beyond the demiurgic picture of God. By giving the name ‘God’ to whatever as yet unknown agent or property or quality might account for this or that particular appearance of design, they have produced a picture of God that it is conceivable the sciences could some day genuinely make obsolete, because it really is a kind of rival explanation to the explanations the sciences seek…

How the Cosmological Fine-Tuning Argument can take us to a Supernatural Creator

|

Every disk is a bubble universe. Universe 1 to Universe 6 are different bubbles, with distinct physical constants that are different from our universe. Our universe is just one of the bubbles. Image courtesy of Krzysztof Mizera and Wikipedia.

The first point I’d like to make is that if someone is attempting to provide a naturalistic explanation for some feature of the universe that appears to indicate cosmic design, then they will have to invoke some larger explanatory framework – i.e. the multiverse. But the multiverse hypothesis is still tied to the concept of a Creator, as physicist Paul Davies has pointed out:

Among the myriad universes similar to ours will be some in which technological civilizations advance to the point of being able to simulate consciousness. Eventually, entire virtual worlds will be created inside computers, their conscious inhabitants unaware that they are the simulated products of somebody else’s technology. For every original world, there will be a stupendous number of available virtual worlds — some of which would even include machines simulating virtual worlds of their own, and so on ad infinitum.

Taking the multiverse theory at face value, therefore, means accepting that virtual worlds are more numerous than “real” ones. There is no reason to expect our world — the one in which you are reading this right now — to be real as opposed to a simulation. And the simulated inhabitants of a virtual world stand in the same relationship to the simulating system as human beings stand in relation to the traditional Creator.

Far from doing away with a transcendent Creator, the multiverse theory actually injects that very concept at almost every level of its logical structure. Gods and worlds, creators and creatures, lie embedded in each other, forming an infinite regress in unbounded space.

— Paul Davies, A Brief History of the Multiverse, New York Times, 12 April 2003

My second point in response to Dr. Hart is that a multiverse would itself need to be fine-tuned, as Dr. Robin Collins has argued in an influential essay entitled, The Teleological Argument: An Exploration of the Fine-Tuning of the Universe (in The Blackwell Companion to Natural Theology, edited by William Lane Craig and J. P. Moreland, 2009, Blackwell Publishing Ltd.):

…[T]he fundamental physical laws underlying a multiverse generator – whether of the inflationary type or some other – must be just right in order for it to produce life-permitting universes, instead of merely dead universes. Specifically, these fundamental laws must be such as to allow the conversion of the mass-energy into material forms that allow for the sort of stable complexity needed for complex intelligent life. For example, … without the Principle of Quantization, all electrons would be sucked into the atomic nuclei, and, hence atoms would be impossible; without the Pauli Exclusion Principle, electrons would occupy the lowest atomic orbit, and hence complex and varied atoms would be impossible; without a universally attractive force between all masses, such as gravity, matter would not be able to form sufficiently large material bodies (such as planets) for life to develop or for long-lived stable energy sources such as stars to exist.

Although some of the laws of physics can vary from universe to universe in superstring/M-Theory, these fundamental laws and principles underlie superstring/M-Theory and therefore cannot be explained as a multiverse selection effect. Further, since the variation among universes would consist of variation of the masses and types of particles, and the form of the forces between them, complex structures would almost certainly be atomlike and stable energy sources would almost certainly require aggregates of matter. Thus, the said fundamental laws seem necessary for there to be life in any of the many universes generated in this scenario, not merely in a universe with our specific types of particles and forces.

In sum, even if an inflationary-superstring multiverse generator exists, it must have just the right combination of laws and fields for the production of life-permitting universes: if one of the components were missing or different, such as Einstein’s equation or the Pauli Exclusion Principle, it is unlikely that any life-permitting universes could be produced. Consequently, at most, this highly speculative scenario would explain the fine-tuning of the constants of physics, but at the cost of postulating additional fine-tuning of the laws of nature.

The multiverse, then, far from solving the fine-tuning problem, merely pushes it up one level.

My third and final point regarding the cosmological argument for Intelligent Design is that the only consistent alternative to design which evades the force of the foregoing arguments is to suppose that we live in a “super-multiverse” where all logical possibilities are realized, in some universe. But if we were to take this supposition seriously, then we could no longer take science seriously. For the number of logically conceivable universes having a history like ours until this point, which then “go off the rails” and behave in a lawless, erratic fashion will vastly exceed the number of universes which stay on the beaten path and continue to behave in a lawlike fashion. Thus if scientists were to adopt the “super-multiverse” hypothesis as an alternative to theism, they should be constantly expecting their own experiments to fail.

I conclude, then, that we already have fairly good grounds for believing in a supernatural Designer. And as I argued above, if one can show that the designed features of the cosmos are essential features, then it follows that the cosmos itself is designed, and not merely its non-essential properties. How might this be done?

An insight from Hogarth

|

William Hogarth, The Painter and his Pug (Self-portrait). 1745. Oil on canvas. Tate Gallery, U.K. Image courtesy of the Yorck Project, DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH, and Wikipedia.

The reader will recall that in the passage quoted above from Dr. Robin Collins, it was the generic features of the multiverse, and not just the particular values of this or that parameter, that pointed to design – “the fundamental physical laws underlying a multiverse generator,” as he put it. “Although some of the laws of physics can vary from universe to universe in superstring/M-Theory, these fundamental laws and principles underlie superstring/M-Theory and therefore cannot be explained as a multiverse selection effect.” At some stage, we reach an ultimate mathematical framework which explains how the multiverse works. If even this framework exhibits features which indicate design, then the design must be an essential feature of the cosmos, rather than a merely incidental one.

Dr. Robin Collins takes this argument further in section 6 of a lecture he gave at Stanford University some years ago, entitled, Universe or Multiverse? A Theistic Perspective, where he shows that the multiverse hypothesis is unable to account for the beauty of the laws of nature. Borrowing a definition from William Hogarth in his 1753 classic The Analysis of Beauty, Collins proposes that simplicity with variety is the defining feature of beauty or elegance. He continues:

The laws of nature seem to manifest just this sort of simplicity with variety: we inhabit a world that could be characterized as a world of fundamental simplicity that gives rise to the enormous complexity needed for intelligent life…

For example, although the observable phenomena have an incredible variety and much seeming chaos, they can be organized via a relatively few simple laws governing postulated unobservable processes and entities. What is more amazing, however, is that these simple laws can in turn be organized under a few higher-level principles … and form part of a simple and elegant mathematical framework…

One way of thinking about the way in which the laws fall under these higher-level principles is as a sort of fine-tuning. If one imagines a space of all possible laws,… the vast majority of variations of these laws end up causing a violation of one of these higher-level principles… Further, for those who are aware of the relevant physics, it is easy to see that in the vast majority of such cases, such variations do not result in new, equally simple higher-level principles being satisfied. It follows, therefore, that these variations almost universally lead to a less elegant and simple set of higher-level physical principles being met. Thus, in terms of the simplicity and elegance of the higher-level principles that are satisfied, the laws of nature we have appear to be a tiny island surrounded by a vast sea of possible law structures that would produce a far less elegant and simple physics…

Further, this “fine-tuning” for simplicity and elegance cannot be explained either by the universe-generator multiverse hypothesis or the metaphysical multiverse hypothesis, since there is no reason to think that intelligent life could only arise in a universe with simple, elegant underlying physical principles. Certainly a somewhat orderly macroscopic world is necessary for intelligent life, but there is no reason to think this requires a simple and elegant underlying set of physical principles.

One way of putting the argument is in terms of the “surprise principle” we invoked in the argument for the fine-tuning of the constants of intelligent life. Specifically, as applied to this case, one could argue that the fact that the phenomena and laws of physics are fine-tuned for simplicity with variety is highly surprising under the non-design hypothesis, but not highly surprising under theism. Thus, the existence of such fine-tuned laws provides significant evidence for theism over the non-design hypothesis.

I am not claiming here that the foregoing argument is mathematically watertight, and I would also acknowledge that much work remains to be done, in terms of expressing the argument in a more precise manner. But the thrust of the argument is clear. If the Designer of the cosmos is responsible for its most fundamental features, then this Designer must also be a Cosmic Creator, and not a mere Demiurge.

2. Biological Intelligent Design and the God of the gaps

|

The genetic code. Image courtesy of Seth Miller, Kosi Gramatikoff, Abgent and Wikipedia.

Having addressed Dr. Hart’s objections to cosmological ID, let us now examine what Dr. Hart has to say about biological ID:

…[I]n the light of traditional theology the argument from irreducible complexity looks irredeemably defective, because it depends on the existence of causal discontinuities in the order of nature, ‘gaps’ where natural causality proves inadequate. But all the classical theological arguments regarding the order of the world assume just the opposite… For Thomas Aquinas, for instance, God creates the order of nature by infusing the things of the universe with the wonderful power of moving themselves toward determinate ends; he uses the analogy of a shipwright able to endow timbers with the power into develop in to a ship without external intervention.

Good and bad gaps

Dr. Hart seems to be assuming here that invoking God to fill an explanatory gap is always a Bad Thing. But as Professor John Lennox argues in Appendix E (“Theistic Evolution and the God of the Gaps”) of his delightfully erudite book, Seven Days that Divide the World (Zondervan, 2011), there are good gaps and bad gaps:

Some gaps are gaps of ignorance and are eventually closed by increased scientific knowledge – they are the bad gaps that figure in the expression, “God of the gaps.” But there are other gaps, gaps that are revealed by advancing science (good gaps). The fact that the information on a printed page is not within the explanatory power of physics and chemistry is not a gap of ignorance; it is a gap which has to do with the nature of writing, and we know how to fill it – with the input of intelligence. (p. 171)

Professor Lennox explains why he believes that the origin of life is a gap of the latter sort:

There is an immense gulf between the non-living and the living that is a matter of kind, and not simply of degree. It is like the gap between the raw materials paper and ink, on the one hand, and the finished product of paper with writing on it, on the other. Raw materials do not self-organize into linguistic structures. Such structures are not “emergent” phenomena, in the sense that they do not appear without intelligent input.

Any adequate explanation for the existence of the DNA-coded database and for the prodigious information storage and processing capabilities of the living cell must involve a source of information that transcends the basic physical chemical materials out of which the cell is constructed… Such processes and programmes, on the basis of all we know from computer science, cannot be explained, even in principle, without the involvement of a mind. (p. 174)

The following two photos will serve to illustrate my point:

|

Above: a bowl of alphabet soup, when it is nearly full.

Below: the same bowl, but nearly empty, with the letters on the side spelling “THE END”. Images courtesy of strawberryblues and Wikipedia.

Living things make use of a digital code, and they contain programs

At this point, Dr. Hart might be inclined to object: “How apt is the comparison between the DNA of living things and alphabet soup?” That’s a reasonable question. I’m certainly not claiming here that we can find propositions embedded in the DNA of organisms. Rather, the claim that I am making is a far more modest one: living things make use of a digital code, which is known as the genetic code. The genetic code is the set of rules by which information encoded within genetic material (DNA or mRNA sequences) is translated into proteins (amino acid sequences) by living cells.

What Intelligent Design proponents contend is that the genetic code is not like a real code; it is a literal code. For an explanation why, I would invite Dr. Hart to peruse Barry Arrington’s post, Yes, KN. It Is a Literal Code and my post, Is the genetic code a real code? The central claim of Dr. Stephen Meyer’s book, Signature in the Cell (HarperOne, New York, 2009) is that the best explanation – indeed, the only causally adequate explanation – for the digital code that we find in the cells of living things is intelligent agency.

But there’s more. Not only do living things make use of a digital code; they also embody a genetic program, which regulates their development. Once again, this is not mere figure of speech: if the reader goes to PubMed and types “genetic program” in the subject field in quotes, over 900 citations will appear. Typing “developmental program” will bring up over 1,300 citations. The following quotes, which are taken from reputable scientific sources, establish the scientific legitimacy of using terms like “instructions,” “code,” “information” and “developmental program” when speaking of an organism’s development (emphases are mine):

“We know that the instructions for how the egg develops into an adult are written in the linear sequence of bases along the DNA of the germ cells.” James Watson et al., Molecular Biology of the Gene (4th Edition, 1987), p. 747.

And from a more recent source:

“The body plan of an animal, and hence its exact mode of development, is a property of its species and is thus encoded in the genome. Embryonic development is an enormous informational transaction, in which DNA sequence data generate and guide the system-wide spatial deployment of specific cellular functions.” (Emerging properties of animal gene regulatory networks by Eric H. Davidson. Nature 468, issue 7326 [16 December 2010]: 911-920. doi:10.1038/nature09645. Davidson is a Professor of Cell Biology at the California Institute of Technology.)

Here’s another recent quote, from an article by Schnorrer et al., on the development of muscle function in the fruitfly Drosophila:

“It is fascinating how the genetic programme of an organism is able to produce such different cell types out of identical precursor cells.” (Schnorrer F., C. Schonbauer, C. Langer, G. Dietzl, M. Novatchkova, K. Schernhuber, M. Fellner, A. Azaryan, M. Radolf, A. Stark, K. Keleman, & B. Dickson, Systematic Genetic Analysis of Muscle Morphogenesis and Function in Drosophila. Nature, 464, 287-291 (11 March 2010). doi:10.1038/nature08799.)

A richer kind of beauty

Here is where the biological argument for Intelligent Design can take us beyond the cosmological argument, which takes cosmic fine-tuning as its starting point. The latter argument points to a Deity Who designed the world, by choosing the underlying mathematical framework for the cosmos, as well as its laws and parameters, and Who then continues to conserve the cosmos in being. All well and good, but there seems to be no need for such a Deity to intervene in the subsequent history of the cosmos. For this reason, many people who find the cosmological version of Intelligent Design attractive are repelled by the biological version: they think it turns God into a cosmic tinkerer, even if His tinkering takes place outside time. Any Deity worthy of the name, they contend, would have designed a cosmos that could produce life automatically, without the need for tinkering.

About eighty years ago, Fr. Ernest Messenger put forward the same argument in his work, Evolution and Catholic Theology: The Problem of Man’s Origin (Macmillan; First American Edition edition, 1932). Messenger invoked an ingenious theological argument to support his contention that God must have made full use of secondary causes in order to produce the bodies of the first human beings. His argument went as follows: God could have done it that way, and He would have done it that way, therefore He did it that way. Messenger justified the first step by appealing to Divine omnipotence. He then explained why he thought God would have used natural causes, as much as possible, in order to produce the first human beings (see here):

This may be thought to be the most debatable point of the three [steps], but we think it is the easiest to answer, in virtue of what we have called the “Principle of Christian Naturalism.” This principle may be expressed as follows: “God makes use of secondary causes wherever possible.” This principle runs counter completely to the ideas of those theologians who argue that because God must have immediately created the human soul, He must also have formed immediately the human body. The principle is such an important one the we must develop in a little.

As St. Thomas points out in his masterly treatment in Contra Gentes, Book III, c. 69, if God has given being to created things, He must also endowed them with activities, and further, if He did not makes use of these activities so far as possible, He would be acting against His own Divine Wisdom.…

This theory of God’s use of secondary causes becomes all the more luminous when we remember that all secondary causes must be regarded ultimately as His instruments. He is the great First Cause, and from Him comes all that has being. Created things would not exist if He did not give them being; they could not produce any effect if He did not concur with their activities and powers. Created agents, then, are instruments in the hands of the Deity…

I would like to suggest that people who argue in this fashion, as Fr. Messenger did eighty years ago, have a limited concept of beauty, which can account for some kinds of beauty that we see in the world, but not the richest kinds. Following Hogarth, these people typically envisage beauty as a delicate and interesting balance between variety and simplicity – or as Leibniz might say, between plenitude and economy. They imagine that a beautiful world should contain many different kinds of things, governed by just a few underlying laws or principles. The variety of elements in the periodic table is a good example of this kind of beauty. It is aesthetically pleasing, because the elements can all be explained in terms of just a few underlying principles: the laws of physics and chemistry, whose underlying mathematical simplicity is evident in their regularity, symmetry and order. Many people would like to think that living things possess the same kind of beauty: an ideal balance between variety and underlying simplicity. Because the underlying laws are mathematically simple in this model of beauty, these people reason that the act of generating things that possess the attribute of beauty should be a simple one. Neo-Darwinism appeals to them as a scientific theory, because it purports to account for the variety of living things we see today, on the basis of a few simple underlying principles (natural selection acting on variation arising stochastically, without any foresight of long-term goals).

The richer beauty of living things: like the beauty of a story

|

A collage of organisms. Courtesy of Azcolvin429 and Wikipedia.

But living things aren’t like the periodic table. The phenomenon that characterizes them is not order, but complexity – and complexity of a particular kind, at that. The beauty you see in a living cell is more like the beauty of a story than the beauty of crystals, which are highly ordered but still not very interesting, even when you contemplate them in all their variety. Stories have a much richer kind of beauty: they have parts (e.g. a beginning, a middle and an end; or the chapters in a novel), and these parts have to be ordered in a sequence specified by the author. The idea of writing a mathematical program that can generate a rich variety of meaningful stories from a “word bank” is comically absurd. Even a master programmer could not do that, unless he/she “cheated” and pre-specified the stories into the program itself. But that wouldn’t save any effort, would it? And one cannot even imagine a simple procedure for writing a good story. Stories are inherently complex, and their parts have to hang together in just the right way, or else they will not “flow” properly.

Someone might suggest that you could generate a very large number of stories by writing one master story and allowing parts of it to vary, like this:

“It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.” (The opening line to George Orwell’s 1984.)

“It was a _____ , _____ day in _____ , and the clocks were striking _____ .”

To be sure, you could generate a very large number of stories that way, but reading them all would be a very monotonous enterprise: there wouldn’t be any real variety. If the stories we generated could only vary within narrow constraints, like the gap-fill sentence above, then they would be very shallow and boring, and would feel “canned.”

The same goes for living things, in all their glorious variety (which can be seen in the picture above). An organism has a story embedded in every cell of its body: its developmental program, which makes it what it is. Since it embodies a story, an organism cannot, even in principle, be produced by a single, simple act. And just as one story cannot be changed step-by-step into another while still remaining a coherent story, so too, it is impossible for one type of living thing to change into another as a result of a gradualistic step-by-step process, while remaining a viable organism. (For those readers who would like to learn more about why such a procedure won’t work, I’d recommend Dr. Branko Kozulic’s article, Proteins and Genes, Singletons and Species, which I blogged about here and here.) And the notion that the ten million-odd species of living things – from bacteria to baobabs to bats – could all be generated by a single program, fails to do justice to their rich variety.

Stories are not like mathematical formulas; and yet, undoubtedly they are still beautiful. They require a lot of work to produce. They are not simple, regular or symmetrical; they have to be specified in considerable detail. Who are we to deny God the privilege of producing life in this way, if He so wishes? The universe is governed by His conception of beauty, not ours, and if it contained nothing but mathematically elegant forms, it would be a boring, sterile place indeed. Crystals are pretty; but life is much richer and more interesting than any crystal. Life cannot be generated with the aid of a few simple rules. It needs to be planned and designed very carefully, in a very “hands-on” fashion. In order to facilitate this, God needs a universe which is ontologically “open” to manipulation by Him whenever He sees fit, rather than a closed, autonomous universe. As I’ll show below, St. Thomas Aquinas actually argued in his writings that the more complex kinds of living things could not have been naturally generated, and there are good grounds for believing that had he known what we know today about living things, he’d be the first to affirm that each and every kind of living thing must have been generated by an act of God.

The beauty found in living things, then, cannot be defined as a balance between plenitude and economy (to use Leibniz’s terms), or (as Hogarth would have put it) between variety and underlying simplicity. It is a different kind of beauty, like that of a story. That is why life needs to be intelligently designed.

St. Thomas Aquinas on ships that can build themselves

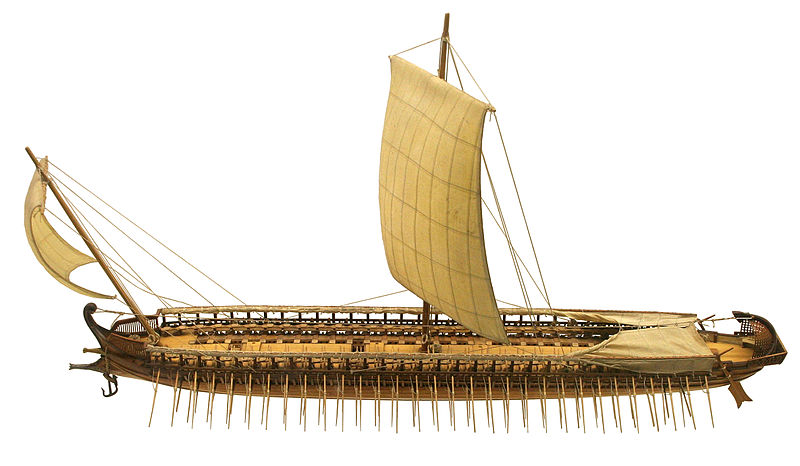

|

Model of a Greek trireme. Deutsches Museum, Munich, Germany. Image courtesy of Sting and Wikipedia.

I’d now like to return to St. Thomas Aquinas and his remarks on ships. In his Commentary on Aristotle’s Metaphysics (Book V, Lesson 2), he writes:

For in every case a first intellectual agent gives to a secondary agent its end and its form of activity; for example, the naval architect gives these to the shipwright, and the first intelligence does the same thing for everything in the natural world.

Thus God endows things with their ends and their various forms of activity. However, Aquinas says nothing here about giving things the power to assemble themselves.

But in his Commentary on Aristotle’s Physics (Book II, lecture 14), Aquinas seems to go considerably further:

…[I]f the art of ship building were intrinsic to wood, a ship would have been made by nature in the same way as it is made by art. And this is most obvious in the art which is in that which is moved, although per accidens, such as in the doctor who cures himself. For nature is very similar to this art.

Hence, it is clear that nature is nothing but a certain kind of art, i.e., the divine art, impressed upon things, by which these things are moved to a determinate end. It is as if the shipbuilder were able to give to timbers that by which they would move themselves to take the form of a ship.

Aquinas is commenting here on a well-known passage in Aristotle’s Physics, in which he contends that just as a skilled craftsman can carry out his work without even thinking about it, so too, natural objects can attain their built-in ends without having to think about them:

It is ridiculous for people to deny that there is purpose if they cannot see the agent of change doing any planning. After all, skill does not make plans. If ship-building were intrinsic to wood, then wood would naturally produce the same results that ship-building does. If skill is purposive, then, so is nature. (Physics 199b26-31, Waterfield translation)

Aquinas, in his commentary on this passage, uses a hypothetical illustration: “If the art of ship building were intrinsic to wood, a ship would have been made by nature in the same way as it is made by art.” However, he nowhere declares that the antecedent is actually possible, and as we shall see, he certainly did not believe that complex organisms could be made in this way.

Now I’d like to ask Dr. Hart two questions. First, does he think that God could, if He wanted, give pieces of wood the power to assemble themselves into a ship? Second, does he think that an affirmative answer to the first question entails that the highly specified complexity which we find in living things could (in principle) have arisen from particles of non-living matter that initially lacked this specificity, via a series of law-governed natural processes?

Regarding the first question: one could perhaps imagine embedding the various pieces of wood with homing devices and identity tags, and even some switches to guarantee that they assembled in the right sequence. But it would be a fool’s enterprise: designing a ship that could assemble itself would be even more work than the task of assembling it oneself. With living things, the problem is much, much worse. The simplest bacterium is M. genitalium, the synthetic version of which has 582,970 base pairs, according to this press release by the J. Craig Venter Institute. Printed in 10 point font, the letters of the M. genitalium JCVI-1.0 genome span 147 pages. The bacterium M. genitalium has a molecular weight of 360,110 kilodaltons (kDa), or 360,110,000 daltons. (One dalton is roughly the mass of a hydrogen atom.) Now try to imagine designing a program for bringing all of the chemical building blocks for this bacterium together, assembling these building blocks in the right way and in the right order, and dealing with all the unplanned contingencies that might conceivably upset the assembly process. Dr. Hart says he doesn’t like a tinkering Deity. Methinks his Deity will have to do a lot more tinkering than mine.

And now, without further ado, I’d like to discuss what Aquinas said about the origin of living things.

Aquinas on spontaneous generation

|

Maggots (pictured above) were believed by St. Thomas Aquinas to be spontaneously generated from decaying matter. Writing in the thirteenth century, Aquinas was unaware that flies can only reproduce sexually. In his terminology, they are “generated from seed.” Image courtesy of Shakey Dawson and Wikipedia.

I imagine that some of my readers will object: “Isn’t it true that Aquinas believed in spontaneous generation? And if he believed that, then he couldn’t possibly have believed that the functional specified complex information we find in living things requires a special act of an Intelligent Agent to produce it, right?”

The short answer to this question is that Aquinas didn’t think the simplest kinds of living things had any significant degree of functional specified complex information in the first place. As Aquinas envisaged them, the simplest living things would have fallen well under the 500-bit threshold which ID proponents take to be the level beyond which we can infer the intervention of an Intelligent Agent.

To illustrate why, I’d like to quote from the following article by I. M. L. Donaldson, entitled Redi’s denial of spontaneous generation in insects, in the Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh 2010; 40:185-6, doi:10.4997/JRCPE.2010.218. The bold type below is mine.

Part of the legacy of the ancient to the early modern world was the belief that living creatures were generated in two distinct ways. The first, generatio univoca, was from parents of the same species. But another type of generation was believed to be common, especially for lower, or at least smaller, animals – ‘spontaneous generation’, generatio aequivoca, in which living things originated from non-living materials such as mud, slime or rotting vegetable or animal matter. Once generated, these creatures might breed by sexual reproduction, but were claimed by some authorities, following Aristotle, not to breed true but to give rise to a different species. For Aristotle, ‘the issue of copulation in lice is nits; in flies, grubs; in fleas, grubs egg-like in shape’ (Historia animalium. Trans. D. A. W. Thompson. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1910. Book 5, chapter 1). A particularly common source of ‘spontaneously’ generated life were the grubs or maggots that appear in rotting animal matter and give rise to flies. The appearance of maggots apparently spontaneously, and of flies from these maggots, seemed to confirm both the occurrence of generatio aequivoca and that its progeny did not breed true. The existence of spontaneous generation was accepted, apparently without question, until the second half of the seventeenth century, and the belief persisted in one form or another until well into the nineteenth.

Aristotle’s views on spontaneous generation, which influenced Aquinas, are described in greater detail in an article by Dr. Eugene McCartney, entitled Spontaneous Generation and Kindred Notions in Antiquity (in Transactions of the American Philological Association, Vol. 51 (1920), pp. 101-115).

For Aquinas, then, the simplest kinds of living things did not even reproduce according to their kind. What’s more – and this is a vital point – Aquinas believed that these living things were not “generated from seed.” Small wonder, then, that Aquinas thought that the action of the heavenly bodies upon the elements was sufficient to generate these simple creatures.

What we know now is that organisms of the kind envisaged by Aquinas do not exist. Omne vivum ex vivo: every living thing comes from another living thing. The information required to make a living thing cannot be found in mud: it can only be found in what Aquinas called “seed.” Aquinas (following Aristotle) erroneously believed that this information-bearing “seed” was contributed by the male parent, while the female contributed only “matter.” But the larger point is that Aquinas recognized that this information-bearing “seed” could not have been generated from a non-living thing.

Aquinas: plants and animals that are “generated from seed” cannot be naturally generated from non-living matter

What did Aquinas actually teach, regarding the origin of living things? According to Aquinas, plants and animals that are “generated from seed” can only be naturally generated by parents of the same kind. Animals that are “generated from seed” can only be naturally generated from the right kind of matter (which had to be supplied by a mother of the same species, according to the Aristotelian biology adopted by Aquinas) and the right kind of form-building agent (the “seed” supplied by a male parent of the same species), which (Aquinas believed) kick-starts the development of the embryo. (Writing in the thirteenth century, Aquinas was unaware that the female ovum also contains information which contributes to the building of the unborn child.)

Aquinas generally used the term “seed” (or “semen”) to refer to the formative agent that kick-started the development of the embryo, but he sometimes also used the term “seed” to refer to the matter out of which the embryo was formed. As he put it in his Summa Theologica I, q. 115 art. 2, Reply to Objection 3:

Reply to Objection 3. The seed of the male is the active principle in the generation of an animal. But that can be called seed also which the female contributes as the passive principle. And thus the word “seed” covers both active and passive principles.

For Aquinas, there are two reasons why plants and animals that are “generated from seed” can only be naturally generated by parents of the same kind. First, each and every kind (or species) of creature has to be generated from the right kind of matter. For animals generated from seed, that matter has to come from a parent of the same species. Second, each and every species has to be generated from the right kind of form-producing agent. For animals generated from seed, that agent is semen from a male parent of the same species.

Aquinas affirms that each and every kind (or species) of creature has to be generated from the right kind of matter, in his discussion of how God made Eve, in his Summa Theologica I, q. 92 art. 2, reply to obj. 2 (Whether woman should have been made for man?). First of all, he argues that each species has to be produced from a special kind of matter:

Reply to Objection 2. Matter is that from which something is made. Now created nature has a determinate principle; and since it is determined to one thing, it has also a determinate mode of proceeding. Wherefore from determinate matter it produces something in a determinate species. On the other hand, the Divine Power, being infinite, can produce things of the same species out of any matter, such as a man from the slime of the earth, and a woman from out of man.

Next, in his Summa Theologica I, q. 92 art. 4 (Whether the woman was formed immediately by God?), Aquinas applies his principle that “the natural generation of every species is from some determinate matter” to the generation of human beings. Aquinas argues that a human being can only be naturally generated from matter derived from another human being:

I answer that, As was said above (2, ad 2), the natural generation of every species is from some determinate matter. Now the matter whence man is naturally begotten is the human semen of man or woman. Wherefore from any other matter an individual of the human species cannot naturally be generated.

In his Commentary on Aristotle’s Physics, Book II, lecture 7, paragraph 204 (Different opinions about fortune and chance, the hidden causes), Aquinas asserts that many kinds of plants and animals can only be generated from the right kind of seed (which can only come from a parent of the same kind):

For it is clear that a thing is not generated from any seed whatsoever, but man from a determinate seed, and the olive from a determinate seed.

Aquinas is even clearer in his discussion of the fifth day of Genesis 1, where he expressly declares in his Summa Theologica I, q. 71 a. 1, reply to obj. 1 (The Work of the Fifth Day), that animals that are “naturally generated from seed” cannot be naturally generated in any other way:

Reply to Objection 1. It was laid down by Avicenna that animals of all kinds can be generated by various minglings of the elements, and naturally, without any kind of seed. This, however, seems repugnant to the fact that nature produces its effects by determinate means, and consequently, those things that are naturally generated from seed cannot be generated naturally in any other way.

Finally, in his Summa Contra Gentiles Book III, chapter 102, paragraph 5 (That God Alone Works Miracles), Aquinas writes that some animals, which he calls “perfect animals,” have to be generated from a “definite kind of semen” coming from a specific kind of agent:

[5] … Of course, corporeal matter may be brought to less perfect actuality by universal power alone, without a particular agent. For example, perfect animals are not generated by celestial power alone, but require a definite kind of semen; however, for the generation of certain imperfect animals, celestial power by itself is enough, without semen.

Aquinas’ argument that animals “generated from seed” must originally have been produced by God

Aquinas explicitly argues that animals “generated from seed” must originally have been produced by God, in two places in his writings.

The first place where Aquinas argues for this conclusion is in his Summa Theologica I, q. 71 art. 1, Reply to Objection 1 (The work of the fifth day). The key point of Aquinas’ argument here is that if certain kinds of animals (namely, those that are “naturally generated from seed”) could only be generated by two parents of the same kind breeding true to type, and if these kinds of animals had a beginning at some point in time, then there was no natural way to generate the first animals of these kinds, as they obviously didn’t have any parents. Aquinas concludes that these kinds of animals must have been originally produced through the immediate action of God alone: “at the first beginning of the world the active principle was the Word of God, which produced animals from material elements.”

The second place where Aquinas addresses this question is in his Summa Contra Gentiles Book II, chapter 43, paragraph 6 (That the distinction of things is not caused by some secondary agent introducing forms into matter). In Aquinas’ day, the movements of the heavenly bodies were regarded as playing a vital part in regulating changes on Earth – including animal reproduction. Even in human reproduction, the movements of the stars were believed to play a vital role. Like most of his contemporaries, Aquinas assumed that for some simple kinds of animals, the action of the heavenly bodies on dead or decaying matter was sufficient to generate the forms of new baby animals. Aquinas then went on to argue that the heavenly bodies were insufficient to generate the forms of new baby animals, for animals that are naturally “generated only from seed,” which Aquinas elsewhere describes as “perfect animals.” For these kinds of animals, the heavenly bodies merely played an enabling role in reproduction, as necessary but not sufficient causes of new forms. These animals cannot be generated from dead or decaying matter; they need parents to generate them. The movement of the heavenly bodies is insufficient to generate these animals “without their pre-existence in the species.” But what about in the beginning? Where did the forms of the first animals come from? Aquinas answers that “the primary establishment of these forms… must of necessity proceed from the Creator alone“:

[6] …There are, however, many sensible forms which cannot be produced by the motion of the heaven except through the intermediate agency of certain determinate principles pre-supposed to their production; certain animals, for example, are generated only from seed. Therefore, the primary establishment of these forms, for producing which the motion of the heaven does not suffice without their pre-existence in the species, must of necessity proceed from the Creator alone.

But the best part is yet to come: Aquinas actually put forward an Intelligent Design argument in his writings, regarding the origin of complex animals.

Aquinas’ Intelligent Design-style argument

|

An excellent example of what St. Thomas Aquinas would have described as a “perfect animal”: a young adult tiger from the Terai in India. Image courtesy of Sumeet Moghe and Wikipedia.

In an age when almost everyone believed that simple animals were spontaneously generated from dead or decaying matter, the philosopher Avicenna (980-1037) had proposed that all animals – even the higher ones – could be generated in this way. In his Summa Theologica I, question 71, reply to objection 1, Aquinas alludes to Avicenna’s views: “It was laid down by Avicenna that animals of all kinds can be generated by various minglings of the elements, and naturally, without any kind of seed.” However, Aquinas disagreed with Avicenna; he thought it was impossible for inanimate forces to generate “perfect animals,” as he called them. We’ve examined one reason why above: according to Aquinas, “perfect animals,” defined broadly as animals that reproduce sexually and breed true to type, can only be naturally generated from “seed” (the formative agent) acting on suitable matter, and both of these have to be supplied by their parents.

But Aquinas also formulated a second argument against Avicenna, based on the complexity of perfect animals, as defined in the narrow sense described above. This argument can be found in his Summa Theologica I, q. 91 art. 2, Reply to Objection 2. Because their bodies are more perfect, more conditions are required to produce them. In modern Intelligent Design terminology, perfect animals exhibit a high degree of specified complexity. According to Aquinas, the heavenly bodies (which were then believed to initiate all changes taking place on Earth) were capable of generating simple animals from properly disposed matter, but they were incapable of producing perfect animals, because too many conditions would need to be specified to produce such creatures by natural means. Readers will be able to see where Aquinas is heading here: only God, he writes, could have acted in the specific way required to produce these complex animals in the beginning. This accords well with Aquinas’ statement in his Summa Contra Gentiles Book II chapter 43, paragraph 6 (That the distinction of things is not caused by some secondary agent introducing forms into matter), which I cited above: the original production of these animals’ forms “must of necessity proceed from the Creator alone.”

In his writings, Aquinas sometimes uses the term “perfect animal” in a broad sense, to denote any animal is naturally “generated from seed” – i.e. an animal that reproduces sexually and breeds true to type (e.g. in his Summa Theologica I, q. 92 art. 1, Summa Contra Gentiles Book III, chapter 102, paragraph 5). But in other passages, Aquinas uses a narrow definition of “perfect animals.” In this narrower, more technical sense, the category of “perfect animals” was roughly equivalent to the class of mammals (excepting very small mammals such as rats and mice, which were believed to be spontaneously generated). For Aristotle, and for Aquinas, “perfect animals,” in the strict sense of that term, are distinguished by the following criteria:

(i) they require a male’s “seed” in order to reproduce. This means that they can only reproduce sexually, and that they always breed true to type – unlike the lower animals, which were then commonly believed to be generated spontaneously from dead matter, and which were incapable of breeding true to type, when reproducing sexually;

(ii) they give birth to live young, instead of laying eggs – in other words, they are viviparous;

(iii) they possess several different senses (unlike the lower animals, which possess only touch);

(iv) they have a greater range of mental capacities, including not only imagination, desire, pleasure and pain (which are found even in the lower animals), but also memory and a variety of passions with a strong cognitive component, including anger;

(v) they are capable of locomotion;

(vi) generally speaking, they live on the land;

(vii) they often hunt lower animals, which are less perfect than themselves; and

(viii) they have complex body parts, owing to their possession of multiple senses and their more active lifestyle (“perfect animals have the greatest diversity of organs” and “they have more distinct limbs”).

Here are a few places where Aquinas describes the complexity of “perfect animals” in his writings:

(a) Commentary on Aristotle’s De Sensu et Sensato, Prologue, Commentary on 436a8 (“For imperfect animals have, of the senses, only touch; they also have imagination, desire, and pleasure and pain, although these are indeterminate in them… But memory and anger are not found in them at all, but only in perfect animals”);

(b) Summa Contra Gentiles Book II chapter 72, paragraph 5 (perfect animals have “the greatest diversity of organs,” because they perform “many operations” when exercising their “powers” – especially their sensory powers such as sight and hearing);

(c) De Coelo, Book II Lecture 2, paragraph 301 (perfect animals “which not only sense but move with local motion, possess all these parts, namely, right and left, before and behind, above and below”);

(d) De Coelo, Book II Lecture 13, paragraph 411 (“For animals of this sort, the more perfect they are, the greater variety do they exhibit in their parts“);

(e) Summa Theologica I, question 71 (perfect animals “have more distinct limbs, and generation of a higher order”);

(f) Summa Theologica I, q. 72 art. 1, Reply to Objection 1 (“their limbs are more distinct and their generation of a higher order“);

(g) Summa Contra Gentiles Book III, chapter 22, paragraph 7 (animals “that are more perfect and more powerful [get their nourishment] from those that are more imperfect and weaker”); and

(h) Summa Contra Gentiles Book II chapter 72, paragraph 5 (That The Soul Is In The Whole Body and Each Of Its Parts):

Now, the higher and simpler a form is, the greater is its power; and that is why the soul, which is the highest of the lower forms, though simple in substance, has a multiplicity of powers and many operations. The soul, then, needs various organs in order to perform its operations, and of these organs the soul’s various powers are said to be the proper acts; sight of the eye, hearing of the ears, etc. For this reason perfect animals have the greatest diversity of organs; plants, the least.

Defined in this narrow sense, “perfect animals” are roughly synonymous with the class of mammals – especially land-dwelling, carnivorous ones – but excluding rats and mice (which were believed to be generated spontaneously, in Aquinas’ day). Birds and most reptiles lay eggs, so they are not “perfect animals” in the narrow sense.

Aquinas explains why inanimate forces – even heavenly bodies, which were then believed to play a vital role in animal reproduction – are incapable of generating these “perfect” animals in his Summa Theologica I, q. 91 art. 2, Reply to Objection 2 (Whether the human body was immediately produced by God). Here’s the relevant passage excerpt:

Reply to Objection 2. Perfect animals, produced from seed, cannot be made by the sole power of a heavenly body, as Avicenna imagined… But the power of heavenly bodies suffices for the production of some imperfect animals from properly disposed matter: for it is clear that more conditions are required to produce a perfect than an imperfect thing.

As we have seen, the reason why Aquinas thought more conditions are required to produce perfect animals is that these animals have more complex body parts, partly due to their possession of several senses, but also because of the demands of their active lifestyle.

In other words, what Aquinas is doing here is sketching an Intelligent Design argument: the complexity of perfect animals’ body parts and the high degree of specificity required to produce them preclude them from having a non-biological origin. The only way in which their forms can be naturally generated is from the father’s “seed,” according to Aquinas. (We now know that both parents contribute genetic information that helps build the form of the embryo, but that doesn’t alter Aquinas’ key point.) From this it follows that the first “perfect animals” must have been produced by God alone.

In his Summa Contra Gentiles Book II chapter 43, paragraph 6 (That the distinction of things is not caused by some secondary agent introducing forms into matter), Aquinas draws precisely this conclusion. Here’s a brief excerpt:

…[A]ll motion toward form is brought about through the mediation of the heavenly motion… There are, however, many sensible forms which cannot be produced by the motion of the heaven except through the intermediate agency of certain determinate principles pre-supposed to their production; certain animals, for example, are generated only from seed. Therefore, the primary establishment of these forms, for producing which the motion of the heaven does not suffice without their pre-existence in the species, must of necessity proceed from the Creator alone.

Of course, a modern evolutionist would respond to Aquinas’ Intelligent Design-style argument by saying that of course, non-living matter cannot instantly transmute into the body of a mammal, as Avicenna thought – that would indeed be a miracle. But over billions of years, it could have produced the first life, which by a series of almost imperceptible step-by-step transitions, could have given rise to living things in all their diversity – including mammals.

But the evolutionist’s response simply assumes that (a) Darwinian evolution is an adequate mechanism to generate not only new species, but also new genera, families, orders, classes and phyla of organisms, and (b) all of the complex structures found in animals could have arisen by natural processes. The former assumption is controversial even among modern evolutionists: there are many biologists who would deny that microevolution can explain macroevolution. And as we have seen, Aquinas disagreed with the latter assumption. Rather, what Aquinas taught was that some changes – in particular, the generation of complex organisms – require so many conditions to be satisfied in order to occur, that they are beyond the power of Nature alone to bring about: they require a special act on God’s part.

From his reading of Aristotle, Aquinas was well aware of (and rejected) the evolutionary theory of the Greek philosopher Empedocles, which posited chance and vast amounts of time in order to account for the origin of living things, so the age of the Earth cannot have been an issue here. Aquinas rebuts Empedocles in his De Veritate q. 5 art. 2, where he argues that “those things that happen by chance, happen only rarely [as] we know from experience.” Empedocles’ theory is deficient, declares Aquinas, because it is unable to account for the fact that “harmony and usefulness are found in nature either at all times or at least for the most part,” which “cannot be the result of mere chance.”

Moreover, Aquinas also expressly taught that existing species did not evolve into new species over time. He believed that the original species of plants and animals had been created in the works of the six days, and that they would last until the end of time, when the movement of the heavens will stop (see his Quaestiones Disputatae De Potentia Dei (Disputed Questions on the Power of God), Question V, article IX). In addition, Aquinas held that the process of generation (from “seed”) always results in an animal or plant of the same type: for example, in his Summa Theologica I, q. 72 art. 1, reply to obj. 3 (The work of the sixth day), Aquinas writes: “In other animals, and in plants, mention is made of genus and species, to denote the generation of like from like.”

In all fairness, it should be pointed out that there was one vital difference between Empedocles’ theory of evolution and Charles Darwin’s: the former was a “chance-only” theory, while the latter presupposed natural laws, and explained the variety of species we find on Earth today in terms of the non-random culling action of natural selection. It should also be added that Aquinas, while aware that hybridization could produce new species (his mentor, Albert the Great, taught him that), was blissfully unaware of genetic mutations. What, one wonders, would he think of the Modern Evolutionary Synthesis?

While Aquinas might well have admired the ingenuity of the Neo-Darwinian theory of evolution, he would also have pointed out that our modern understanding of genetics has exacerbated the problem of accounting for complexity to the n-th degree: living things are far, far more complex than he imagined them to be, in the thirteenth century. In other words, the number of conditions required to make a complex organism – or a lowly bacterium, for that matter – is orders of magnitude greater than what Aquinas supposed it was, in his day. In order to account for this complexity, then, we need a theory of evolution that is orders of magnitude more efficient than former theories. And it is precisely here that evolution’s Achilles heel becomes apparent. In my post, At last, a Darwinist mathematician tells the truth about evolution, I explain why according to Professor Gregory Chaitin’s calculations, Darwinian evolution should take quintillions of years, rather than billions of years, to generate the life-forms we see on Earth today. And that assumes that you have a living thing, in the first place. Professor John Walton, a Research Professor of Chemistry at St. Andrews University who holds not one but two doctorates, has explained why he believes Intelligent Design is the only adequate explanation of the origin of life, in an interesting online talk.

Since Aquinas’ central objection to the notion that non-living matter could give rise to complex animals related to the number of conditions that needed to be satisfied, and since the number of conditions has increased exponentially since he wrote in the thirteenth century, I think it is fair to conclude that he would not be satisfied with neo-Darwinism, either scientifically or theologically. Far from science filling in the gaps, the gaps have grown. Even the bacterial flagellum, whose origin was said to be all wrapped up at the Dover trial (see here), now appears to be an even more stunning marvel than it was a few years ago (see this recent talk on the bacterial flagellum by geneticist Dr. Scott Minnich).

Dr. Hart, as we have seen, objects to the notion of “causal discontinuities in the order of nature, ‘gaps’ where natural causality proves inadequate,” arguing that for Aquinas, “God creates the order of nature by infusing the things of the universe with the wonderful power of moving themselves toward determinate ends.” But as we have seen, that’s not what Aquinas holds: for him, each and every species of organism “generated from seed” requires an act of God to account for its origin. What’s more, for Aquinas, gaps of this sort are good gaps, since God’s power and voluntary agency “can be manifested in no better way … than by the fact that He sometimes does something outside the order of nature.” I can only conclude that Aquinas’ thinking is very much at odds with Dr. Hart’s, on the subject of Intelligent Design.

Before I discuss what Aquinas would have made of the modern-day Intelligent Design movement, I’d like to mention what he says about the production of the first man, Adam.

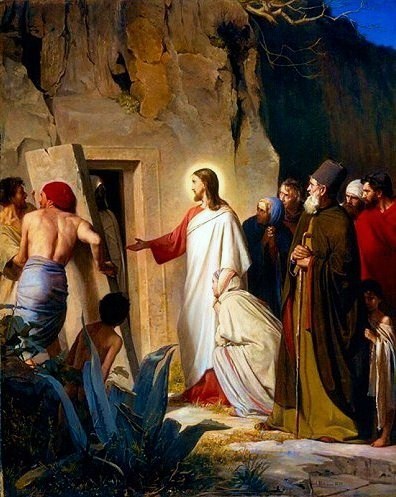

Aquinas on the production of Adam

|

St. Thomas Aquinas held that the production of Adam’s body from slime was just as much of a miracle as the act of raising the dead. The picture above is titled: Raising Lazarus. Oil on Copper Plate, 1875, Carl Heinrich Bloch (Hope Gallery, Salt Lake City). Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Nowhere is Aquinas more explicit on the fact that the production of the first animals must have been an event beyond the order of Nature than in his discussion of the production of Adam’s body.

In his Summa Theologica I, q. 91, article 2 (Whether the human body was immediately produced by God), Aquinas expressly teaches that only God was capable of producing the forms of the first human beings, Adam and Eve. According to Aquinas, not even intelligent spiritual beings, such as the angels, were capable of producing the first human body – even when working with pre-existing matter. Only God could have done this. As Aquinas explained in his Summa Theologica I, q. 65 art. 4, “the corporeal forms that bodies had when first produced came immediately from God, whose bidding alone matter obeys, as its own proper cause.” Thus according to Aquinas, angels have no power to command matter to assume complex forms; only God, the Creator of matter, can do that.

In the same passage, Aquinas responds to an objection to the idea that supernatural agency was responsible for the formation of Adam’s body: since the production of the first human body was a material change, it should have a naturalistic explanation. In St. Thomas’ day, all changes occurring on earth were supposed to be explicable in terms of the movements of heavenly bodies, so (the objection went) we should be able to explain the appearance of the first human body in the same way. Aquinas responds that some material changes are beyond the power of Nature to produce. In this passage, Aquinas even likens the production of Adam’s body from slime to the miracle of raising the dead to life, showing that he regarded it as clearly beyond the power of Nature:

Objection 3. Further, nothing is made of corporeal matter except by some material change. But all corporeal change is caused by a movement of a heavenly body, which is the first movement. Therefore, since the human body was produced from corporeal matter, it seems that a heavenly body had part in its production.

Reply to Objection 3. The movement of the heavens causes natural changes; but not changes that surpass the order of nature, and are caused by the Divine Power alone, as for the dead to be raised to life, or the blind to see: like to which also is the making of man from the slime of the earth.

Why didn’t Aquinas include his Intelligent Design argument in his Five Ways?

Readers might be wondering why Aquinas did not choose to include his Intelligent Design-style argument that the first animals had to have been created by God, in his famous proofs of the existence of God. The short answer is that back in the thirteenth century, Aquinas had no way of showing that the universe had a beginning – indeed, he even argued that it could not be philosophically proved – and hence, no way of demonstrating that there were any “first animals.” A thirteenth century atheist, confronted with Aquinas’ Intelligent Design argument, could reply that for all we know, animals and human beings might always have existed. Hence it would have been question-begging for Aquinas to use this argument as a proof of God. What he would insist, however, is that if the universe had a beginning, the the first animals must have been generated by a special act of God.

I use the term “act of God” here, because it is not my intention to argue in this essay that biological Intelligent Design requires a supernatural miracle (although Aquinas apparently thought it did). We can suppose – as I do – that living things share a common descent, without committing ourselves to the assumption that natural processes lacking foresight (e.g. random variation culled by natural selection) are sufficient to generate life in all its diversity. Exactly how God guides these processes to generate creatures is none of my concern. What matters to me is that an Infusion of Intelligence is required, in order to generate the life-forms we find on Earth today. The question of whether God used a miracle to generate life is a secondary one.

What would Aquinas have made of modern Intelligent Design arguments?

In his Summa Contra Gentiles Book III, chapter 104 (see paragraphs 2 and 3), Aquinas argues that “speech is itself an act peculiar to a rational nature.” I would argue that if it could be shown that there is an actual set of programs running within each cell in the body of a living organism, with coded instructions – the language of the cell – for maintaining each cell’s biological processes, then St. Thomas would immediately have deduced that no natural physical process could possibly have created it.

We have seen already that living things make use of a digital code, which is called the genetic code. I’d now like to say more about the programs that run within the cells of living things.

Intelligent Design advocate Dr. Don Johnson has both a Ph.D. in chemistry and a Ph.D. in computer and information sciences. On April 8, 2010, Dr. Johnson gave a presentation entitled Bioinformatics: The Information in Life for the University of North Carolina Wilmington chapter of the Association for Computer Machinery. Dr. Johnson’s presentation is now on-line here. Both the talk and accompanying handout notes can be accessed from Dr. Johnson’s Web page. Dr. Johnson spent 20 years teaching in universities in Wisconsin, Minnesota, California, and Europe.

On a slide entitled “Information Systems In Life,” Dr. Johnson points out that:

- the genetic system is a pre-existing operating system;

- the specific genetic program (genome) is an application;

- the native language has a codon-based encryption system;

- the codes are read by enzyme computers with their own operating system;

- each enzyme’s output is to another operating system in a ribosome;

- codes are decrypted and output to tRNA computers;

- each codon-specified amino acid is transported to a protein construction site; and

- in each cell, there are multiple operating systems, multiple programming languages, encoding/decoding hardware and software, specialized communications systems, error detection/correction systems, specialized input/output for organelle control and feedback, and a variety of specialized “devices” to accomplish the tasks of life.

To sum up: the use of the word “program” to describe the workings of the cell is scientifically respectable. It is not just a figure of speech. It is literal. Additionally, the various programs running within the cell constitute a paradigm of excellent programming: no human engineer is currently capable of designing programs for building and maintaining an organism that work with anything like the same degree of efficiency as the programs running an E. coli cell, let alone a cell in the body of a human being.

Cells, it is true, do not communicate with one another by means of propositions. But they do use a literal code, and they do run according to literal programs. They are semiotic systems. Given his remarks on speech as a hallmark of rationality, Aquinas would surely be the first to agree that intelligent agency is the only causally adequate explanation for the origin of living cells, and that semiotic systems are beyond the power of Nature to produce.

Some might wonder, though, whether Aquinas would object to the theologically lop-sided approach of the Intelligent Design movement. Or as Dr. Hart put it: “According to the classical arguments, universal rational order – not just this or that particular instance of complexity – is what speaks of the divine mind.” I discussed this objection above, but I would like to add here that Aquinas was a preacher himself. As a preacher, he realized the importance of adapting his message to his audience. In today’s world, science is commonly regarded as the only source of knowledge, aside from the truths of logic and mathematics, and metaphysical intuitions – even the obvious intuition that something cannot come from nothing – are regarded with profound mistrust. Faced with such an audience, where do you think Aquinas would urge us to start, were he alive today?

The obvious place to begin, then, is with arguments that impress people – in other words, arguments based on the specified complexity of living things and/or the fine-tuning of the cosmos. Having done that, people may then be persuaded to re-examine their Humean metaphysical assumptions, which keep their minds permanently closed to the possibility of there being a God. Their eyes having been opened, they may at last recognize the “universal rational order” which is right in front of their nose, and which they have ignored their whole lives.

I should close by saying that I have the greatest respect for Dr. Hart’s learning, and that I have written this post in a spirit of constructive dialogue.