|

|

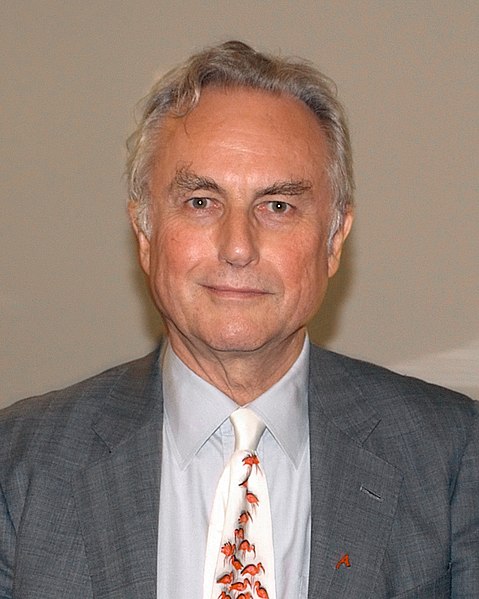

For several years now, Professor Richard Dawkins, the renowned evolutionary biologist and author of The God Delusion, has refused to debate the topic of God’s existence with the philosopher and Christian apologist, Professor William Lane Craig. That is Professor Dawkins’ privilege; he is under no obligation to debate with anyone. Until recently, Dawkins’ favorite reason for refusing to face off against Professor William Lane Craig was that Craig was nothing more than a professional debater. But now, in an article in The Guardian (20 October 2011) entitled, Why I refuse to debate with William Lane Craig, Richard Dawkins leads off by firing this salvo: “This Christian ‘philosopher’ is an apologist for genocide. I would rather leave an empty chair than share a platform with him.”

In the same article, Professor Dawkins savagely castigates William Lane Craig for his willingness to justify “genocides ordered by the God of the Old Testament”. According to Dawkins, “Most churchmen these days wisely disown the horrific genocides ordered by the God of the Old Testament” – unlike Craig, who argues that “the Canaanites were debauched and sinful and therefore deserved to be slaughtered.” Dawkins then quotes William Lane Craig as justifying the slaughter on the grounds that: (i) if these children had been allowed to live, they would have turned the Israelites towards serving the evil Canaanite gods; and (ii) the children who were slaughtered would have gone to Heaven instantly when they died, so God did them no wrong in taking their lives. Dawkins triumphantly concludes:

Would you shake hands with a man who could write stuff like that? Would you share a platform with him? I wouldn’t, and I won’t. Even if I were not engaged to be in London on the day in question, I would be proud to leave that chair in Oxford eloquently empty.

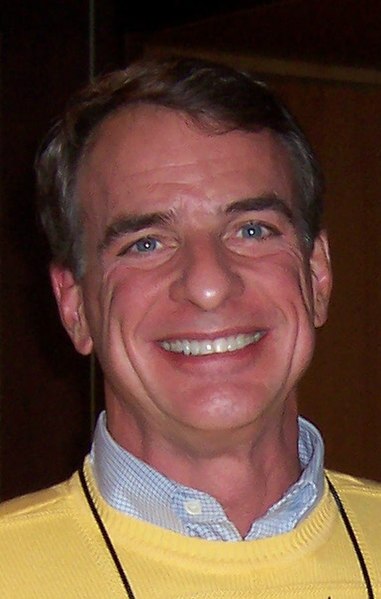

Professor Dawkins, allow me to briefly introduce myself. My name is Vincent Torley (my Web page is here), and I have a Ph.D. in philosophy. I’m an Intelligent Design proponent who also believes that modern life-forms are descended from a common ancestor that lived around four billion years ago. I’m an occasional contributor to the Intelligent Design Website, Uncommon Descent. Apart from that, I’m nobody of any consequence.

Professor Dawkins, I have ten charges to make against you, and they relate to apparent cases of lying, hypocrisy and moral inconsistency on your part. Brace yourself. I’ve listed the charges for the benefits of people reading this post.

|

My Ten Charges against Professor Richard Dawkins

1. Professor Dawkins has apparently lied to his own readers at the Richard Dawkins Foundation for Reason and Science. In a recent post (dated 1 May 2011) he stated that he “didn’t know quite how evil [William Lane Craig’s] theology is” until atheist blogger Greta Christina alerted him to Craig’s views in an article she wrote on 25 April 2011, when in fact, Dawkins had already read Professor Craig’s “staggeringly awful” essay on the slaughter of the Canaanites and blogged about it in his personal forum (http://forum.richarddawkins.net), three years earlier, on 21 April 2008. In other words, Professor Dawkins’ alleged shock at recently discovering Craig’s “evil” views turns out to have been feigned: he knew about these views some years ago. 2. Professor Dawkins has recently maligned Professor William Lane Craig as a “fundamentalist nutbag” who isn’t even a real philosopher and whose only claim to fame is that he is a professional debater, but his own statements about Craig back in 2008 completely contradict these assertions. Moreover, Dawkins’ characterization of Craig as a “fundamentalist nutbag” is particularly unjust, given that Professor Craig has admitted that he’s quite willing to change his mind on the slaughter of the Canaanites, if proven wrong. Although Professor Craig upholds Biblical inerrancy, he does so provisionally: he says it’s possible that the Bible might be sometimes wrong on moral matters, and furthermore, he acknowledges that the Canaanite conquest might not have even happened, as an historical event. That certainly doesn’t sound like the writings of a “nutbag” to me. 3. Professor Dawkins says that he refuses to share a platform with William Lane Craig, because of his views on the slaughter of the Canaanites, but he has already debated someone who holds substantially the same views as Craig on the slaughter of the Canaanites. On 23 October 1996, Dawkins debated Rabbi Shmuley Boteach, who also believes that the slaughter of the Canaanites was morally justified under the circumstances at the time (see here and here). What’s more, in 2006, Dawkins appeared in a television panel with Professor Richard Swinburne, who holds the same view. Dawkins might reply that Swinburne did not make his views on the slaughter of the Canaanites public until 2011, but as I shall argue below, he can hardly make the same excuse about not knowing Rabbi Boteach’s views. If he did not know, then he was extraordinarily naive. 4. Professor Dawkins refuses on principle to share a platform with William Lane Craig because of his views on the slaughter of the Canaanites, yet he is perfectly willing to share a platform with atheists whose moral opinions are far more horrendous: Dan Barker, who says that child rape could be moral if it were absolutely necessary in order to save humanity; Dr. Sam Harris, who says that pushing an innocent man into the path of an oncoming train is OK, if it is necessary in order to save a greater number of human lives; and Professor Peter Singer, who believes that sex with animals is not intrinsically wrong, if both parties consent. 5. Professor Dawkins refuses to share a platform with William Lane Craig, who holds that God commanded the Israelites to slaughter Canaanite babies whom He subsequently recompensed with eternal life in the hereafter. However, he is quite happy to share a platform with Professor P. Z. Myers, who doesn’t even regard newborn babies as people with a right to life. (See here for P.Z. Myers’ original post, here for one reader’s comment and here for P. Z. Myers’ reply, in which he makes his own views plain.) Nor does Professor Peter Singer, whom Dawkins interviewed back in 2009, regard newborn babies as people with a right to life. (See this article.) 6. Apparently Professor Dawkins himself does not believe that a newborn human baby is a person with the same right to life that you or I have, and does not believe that the killing of a healthy newborn baby is just as wrong as the act of killing you or me. For he sees nothing intrinsically wrong with the killing of a one- or two-year-old baby suffering from a horrible incurable disease, that meant it was going to die in agony in later life (see this video at 24:12). He also claims in The God Delusion (Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., 2006, p. 293) that the immorality of killing an individual is tied to the degree of suffering it is capable of. By that logic, it must follow that killing a healthy newborn baby, whose nervous system is still not completely developed, is not as bad as killing an adult. 7. In his article in The Guardian (20 October 2011) condemning William Lane Craig, Professor Dawkins fails to explain exactly why it would be wrong under all circumstances for God (if He existed) to take the life of an innocent human baby, if that baby was compensated with eternal life in the hereafter. In fact, as I will demonstrate below, if we look at the most common arguments against killing the innocent, then it is impossible to construct a knock-down case establishing that this act of God would be wrong under all possible circumstances. Strange as it may seem, there are always some possible circumstances we can envisage, in which it might be right for God to act in this way. 8. Professor Dawkins declines to say whether he agrees with some of his fans and followers, who consider the God of the Old Testament to be morally equivalent to Hitler (see here and here for examples). However, the very comparison is odious, for in the same Old Testament books which Dawkins condemns, God exhorts the Israelites: “Do not seek revenge”; “Love your neighbor as yourself” and: “The foreigner residing among you must be treated as your native-born. Love them as yourself, for you were foreigners in Egypt. I am the LORD your God.” (Leviticus 19:18, 33-34, NIV.) That certainly doesn’t sound like Hitler to me – and I’ve personally visited Auschwitz and Birkenau. I wonder if Professor Dawkins has. 9. Dawkins singles out Professor William Lane Craig for condemnation as a “fundamentalist nutbag”, but he fails to realize that Professor William Lane Craig’s views on the slaughter of the Canaanites were shared by St. Augustine, St. Thomas Aquinas, John Calvin, the Bible commentator Matthew Henry, and John Wesley, as well as some modern Christian philosophers of eminent standing, such as Richard Swinburne, whom he appeared on a television panel with in 2006. Is he prepared to call all these people “nutbags” too? That’s a lot of crazy people, I must say. 10. Unlike the late Stephen Jay Gould (who maintained that the experiment would be just about the most unethical thing he could imagine), Professor Dawkins believes that the creation of a hybrid between humans and chimps “might be a very moral thing to do”, so long as it was not exploited or treated like a circus freak (see this video at 40:33), although he later concedes that if only one were created, it might get lonely (perhaps a group of hybrids would be OK, then?) Dawkins has destroyed his own moral credibility by making such a ridiculous statement. How can he possibly expect us to take him seriously when he talks about ethics, from now on? |

Professor Dawkins, I understand that you are a very busy man. Nevertheless, I should warn you that a failure to answer these charges will expose you to charges of apparent lying, character assassination, public hypocrisy, as well as an ethical double-standard on your part. The choice is yours.

Read the rest of the article here.