In a day when first principles of reason are at a steep discount, it is unsurprising to see that inductive reasoning is doubted or dismissed in some quarters.

And yet, there is still a huge cultural investment in science, which is generally understood to pivot on inductive reasoning.

Where, as the Stanford Enc of Phil notes, in the modern sense, Induction ” includes all inferential processes that “expand knowledge in the face of uncertainty” (Holland et al. 1986: 1), including abductive inference.” That is, inductive reasoning is argument by more or less credible but not certain support, especially empirical support.

How could it ever work?

A: Surprise — NOT: by being an application of the principle of (stable) distinct identity. (Which is where all of logic seems to begin!)

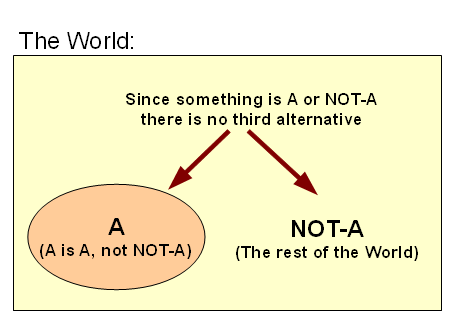

Let’s refresh our thinking, partitioning World W into A and ~A, W = {A|~A}, so that (physically or conceptually) A is A i/l/o its core defining characteristics, and no x in W is A AND also ~A in the same sense and circumstances, likewise any x in W will be A or else ~A, not neither nor both. That is, once a dichotomy of distinct identity occurs, it has consequences:

Where also, we see how scientific models and theories tie to the body of observations that are explained or predicted, with reliable explanations joining the body of credible but not utterly certain knowledge:

As I argued last time:

>>analogical reasoning [–> which is closely connected to inductive reasoning] “is fundamental to human thought” and analogical arguments reason from certain material and acknowledged similarities (say, g1, g2 . . . gn) between objects of interest, say P and Q to further similarities gp, gp+1 . . . gp+k. Also, observe that analogical argument is here a form of inductive reasoning in the modern sense; by which evidence supports and at critical mass warrants a conclusion as knowledge, but does not entail it with logical necessity.

How can this ever work reliably?

By being an application of the principle of identity.

Where, a given thing, P, is itself in light of core defining characteristics. Where that distinctiveness also embraces commonalities. That is, we see that if P and Q come from a common genus or archetype G, they will share certain common characteristics that belong to entities of type G. Indeed, in computing we here speak of inheritance. Men, mice and whales are all mammals and nurture their young with milk, also being warm-blooded etc. Some mammals lay eggs and some are marsupials, but all are vertebrates, as are fish. Fish and guava trees are based on cells and cells use a common genetic code that has about two dozen dialects. All of these are contingent embodied beings, and are part of a common physical cosmos.

This at once points to how an analogy can be strong (or weak).

For, if G has in it common characteristics {g1, g2 . . . gn, | gp, gp+1 . . . gp+k} then if P and Q instantiate G, despite unique differences they must have to be distinct objects, we can reasonably infer that they will both have the onward characteristics gp, gp+1 . . . gp+k. Of course, this is not a deductive demonstration, at first level it is an invitation to explore and test until we are reasonably, responsibly confident that the inference is reliable. That is the sense in which Darwin reasoned from artificial selection by breeding to natural selection. It works, the onward debate is the limits of selection.>>

Consider the world, in situation S0, where we observe a pattern P. Say, a bright, red painted pendulum swinging in a short arc and having a steady period, even as the swings gradually fade away. (And yes, according to the story, this is where Galileo began.) Would anything be materially different in situation S1, where an otherwise identical bob were bright blue instead? (As in, strip the bob and repaint it.)

“Obviously,” no.

Why “obviously”?

We are intuitively recognising that the colour of paint is not core to the aspect of behaviour we are interested in. A bit more surprising, within reason, the mass of the bob makes little difference to the slight swing case we have in view. Length of suspension does make a difference as would the prevailing gravity field — a pendulum on Mars would have a different period.

Where this points, is that the world has a distinct identity and so we understand that certain things (here comes that archetype G again) will be in common between circumstances Si and Sj. So, we can legitimately reason from P to Q once that obtains. And of course, reliability of behaviour patterns or expectations so far is a part of our observational base.

Avi Sion has an interesting principle of [provisional] uniformity:

>>We might . . . ask – can there be a world without any ‘uniformities’? A world of universal difference, with no two things the same in any respect whatever is unthinkable. Why? Because to so characterize the world would itself be an appeal to uniformity. A uniformly non-uniform world is a contradiction in terms.

Therefore, we must admit some uniformity to exist in the world.

The world need not be uniform throughout, for the principle of uniformity to apply. It suffices that some uniformity occurs. Given this degree of uniformity, however small, we logically can and must talk about generalization and particularization. There happens to be some ‘uniformities’; therefore, we have to take them into consideration in our construction of knowledge. The principle of uniformity is thus not a wacky notion, as Hume seems to imply . . . .

The uniformity principle is not a generalization of generalization; it is not a statement guilty of circularity, as some critics contend. So what is it? Simply this: when we come upon some uniformity in our experience or thought, we may readily assume that uniformity to continue onward until and unless we find some evidence or reason that sets a limit to it. Why? Because in such case the assumption of uniformity already has a basis, whereas the contrary assumption of difference has not or not yet been found to have any. The generalization has some justification; whereas the particularization has none at all, it is an arbitrary assertion.

It cannot be argued that we may equally assume the contrary assumption (i.e. the proposed particularization) on the basis that in past events of induction other contrary assumptions have turned out to be true (i.e. for which experiences or reasons have indeed been adduced) – for the simple reason that such a generalization from diverse past inductions is formally excluded by the fact that we know of many cases [of inferred generalisations; try: “we can make mistakes in inductive generalisation . . . “] that have not been found worthy of particularization to date . . . .

If we follow such sober inductive logic, devoid of irrational acts, we can be confident to have the best available conclusions in the present context of knowledge. We generalize when the facts allow it, and particularize when the facts necessitate it. We do not particularize out of context, or generalize against the evidence or when this would give rise to contradictions . . . [Logical and Spiritual Reflections, BK I Hume’s Problems with Induction, Ch 2 The principle of induction.]>>

So, by strict logic, SOME uniformity must exist in the world, the issue is to confidently identify reliable cases, however provisionally. So, even if it is only that “we can make mistakes in generalisations,” we must rely on inductively identified regularities of the world.Where, this is surprisingly strong, as it is in fact an inductive generalisation. It is also a self-referential claim which brings to bear a whole panoply of logic; as, if it is assumed false, it would in fact have exemplified itself as true. It is an undeniably true claim AND it is arrived at by induction so it shows that induction can lead us to discover conclusions that are undeniably true!

Therefore, at minimum, there must be at least one inductive generalisation which is universally true.

But in fact, the world of Science is a world of so-far successful models, the best of which are reliable enough to put to work in Engineering, on potential risk of being found guilty of tort in court.

Illustrating:

How is such the case? Because, observing the reliability of a principle is itself an observation, which lends confidence in the context of a world that shows a stable identity and a coherent, orderly pattern of behaviour. Or, we may quantify. Suppose an individual observation O1 is 99.9% reliable. Now, multiply observations, each as reliable, the odds that all of these are somehow collectively in a consistent error falls as (1 – p)^n. Convergent, multiplied credibly independent observations are mutually, cumulatively reinforcing, much as how the comparatively short, relatively weak fibres in a rope can be twisted and counter-twisted together to form a long, strong, trustworthy rope.

And yes, this is an analogy.

(If you doubt it, show us why it is not cogent.)

So, we have reason to believe there are uniformities in the world that we may observe in action and credibly albeit provisionally infer to. This is the heart of the sciences.

What about the case of things that are not directly observable, such as the micro-world, historical/forensic events [whodunit?], the remote past of origins?

That is where we are well-advised to rely on the uniformity principle and so also the principle of identity. We would be well-advised to control arbitrary speculation and ideological imposition by insisting that if an event or phenomenon V is to be explained on some cause or process E, the causal mechanism at work C should be something we observe as reliably able to produce the like effect. And yes, this is one of Newton’s Rules.

For relevant example, complex, functionally specific alphanumerical text (language used as messages or as statements of algorithms) has but one known cause, intelligently directed configuration. Where, it can be seen that blind chance and/or mechanical necessity cannot plausibly generate such strings beyond 500 – 1,000 bits of complexity. There just are not enough atoms and time in the observed cosmos to make such a blind needle in haystack search a plausible explanation. The ratio of possible search to possible configurations trends to zero.

So, yes, on its face, DNA in life forms is a sign of intelligently directed configuration as most plausible cause. To overturn this, simply provide a few reliable cases of text of the relevant complexity coming about by blind chance and/or mechanical necessity. Unsurprisingly, random text generation exercises [infinite monkeys theorem] fall far short, giving so far 19 – 24 ASCII characters, far short of the 72 – 143 for the threshold. DNA in the genome is far, far beyond that threshold, by any reasonable measure of functional information content.

Similarly, let us consider the fine tuning challenge.

The laws, parameters and initial circumstances of the cosmos turn out to form a complex mathematical structure, with many factors that seem to be quite specific. Where, mathematics is an exploration of logic model worlds, their structures and quantities. So, we can use the power of computers to “run” alternative cosmologies, with similar laws but varying parameters. Surprise, we seem to be at a deeply isolated operating point for a viable cosmos capable of supporting C-Chemistry, cell-based, aqueous medium, terrestrial planet based life. Equally surprising, our home planet seems to be quire privileged too. And, if we instead posit that there are as yet undiscovered super-laws that force the parameters to a life supporting structure, that then raises the issue, where did such super-laws come from; level-two fine tuning, aka front loading.

From Barnes:

That is, the fine tuning observation is robust.

There is a lot of information caught up in the relevant configurations, and so we are looking again at functionally specific complex organisation and associated information.

(Yes, I commonly abbreviate: FSCO/I. Pick any reasonable index of configuration-sensitive function and of information tied to such specific functionality, that is a secondary debate, where it is not plausible that say the amount of information in DNA and proteins or in the cluster of cosmological factors is extremely low. FSCO/I is also a robust phenomenon, and we have an Internet full of cases in point multiplied by a world of technology amounting to trillions of cases that show that it has just one commonly observed cause, intelligently directed configuration. AKA, design.)

So, induction is reasonable, it is foundational to a world of science and technology.

It also points to certain features of our world of life and the wider world of the physical cosmos being best explained on design, not blind chance and mechanical necessity.

Those are inductively arrived at inferences, but induction is not to be discarded at whim, and there is a relevant body of evidence.

Going forward, can we start from this? END

PS: Per aspect (one after the other) Explanatory Filter, adapting Dembski et al: