[This post will remain at the top of the page until 10:00 am EST tomorrow, May 22. For reader convenience, other coverage continues below. – UD News]

|

|

|

|

In a recent interview with The Guardian, Professor Stephen Hawking shared with us his thoughts on death:

I have lived with the prospect of an early death for the last 49 years. I’m not afraid of death, but I’m in no hurry to die. I have so much I want to do first. I regard the brain as a computer which will stop working when its components fail. There is no heaven or afterlife for broken down computers; that is a fairy story for people afraid of the dark.

Now, Stephen Hawking is a physicist, not a biologist, so I can understand why he would compare the brain to a computer. Nevertheless, I was rather surprised that Professor Jerry Coyne, in a recent post on Hawking’s remarks, let the comparison slide without comment. Coyne should know that there are no less than ten major differences between brains and computers, a fact which vitiates Hawking’s analogy. (I’ll say more about these differences below.)

But Professor Coyne goes further: not only does he equate the human mind with the human brain (as Hawking does), but he also regards the evolution of human intelligence as no more remarkable than the evolution of skunk butts, according to a recent report by Faye Flam in The Philadelphia Inquirer:

Many biologists are not religious, and few see any evidence that the human mind is any less a product of evolution than anything else, said Chicago’s Coyne. Other animals have traits that set them apart, he said. A skunk has a special ability to squirt a caustic-smelling chemical from its anal glands.

Our special thing, in contrast, is intelligence, he said, and it came about through the same mechanism as the skunk’s odoriferous defense.

In a recent post, Coyne defiantly reiterated his point, declaring: “I absolutely stand by my words.”

So today, I thought I’d write about three things: why the brain is not like a computer, why the evolution of the brain is not like the evolution of the skunk’s butt, and why the human mind cannot be equated with the human brain. Of course, proving that the mind and the brain are not the same doesn’t establish that there is an afterlife; still, it leaves the door open to that possibility, particularly if you happen to believe in God.

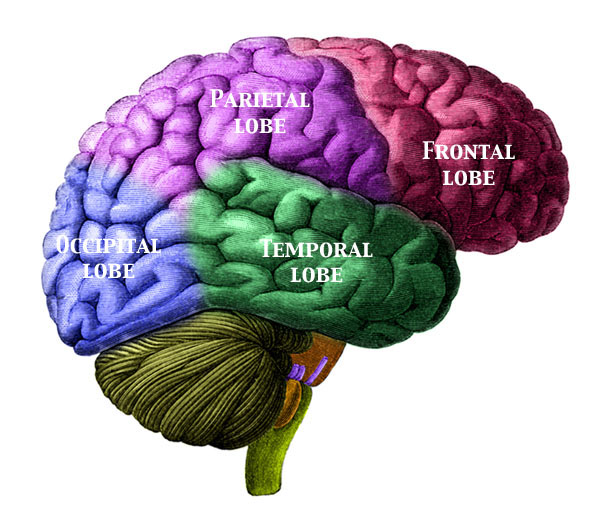

Why the brain is not like a computer

For readers wishing to understand why the human brain is not like a computer, I would highly recommend a 2007 blog article entitled, 10 Important Differences Between Brains and Computers, by Chris Chatham, a 2nd year Grad student pursuing a Ph.D. in Cognitive Neuroscience at the University of Colorado, Boulder, over on his science blog, Developing Intelligence. Let me say at the outset that Chatham is a materialist who believes that the human mind supervenes upon the human brain. Nevertheless, he regards the brain-computer metaphor as being of very limited value, insofar as it obscures the many ways in which the human brain exceeds a computer in flexibility, parallel processing and raw computational power, not to mention the fact that the human brain is part of a living human body.

Anyway, here is a short, non-technical summary of the ten differences between brains and computers which are discussed by Chatham:

1. Brains are analogue; computers are digital.

Digital 0’s and 1’s are binary (“on-off”). However, the brain’s neuronal processing is directly influenced by processes that are continuous and non-linear. Because early computer models of the human brain overlooked this simple point, they severely under-estimated the information processing power of the brain’s neural networks.

2. The brain uses content-addressable memory.

Computers have byte-addressable memory, which relies on information having a precise address. With the brain’s content-addressable memory, on the other hand, information can be accessed by “spreading activation” from closely-related concepts. As Chatham explains, your brain has a built-in Google, allowing an entire memory to be retrieved from just a few cues (key words). Computers can only replicate this feat by using massive indices.

3. The brain is a massively parallel machine; computers are modular and serial.

Instead of having different modules for different capacities or functions, as a computer does, the brain often uses one and the same area for a multitude of functions. Chatham provides an example: the hippocampus is used not only for short-term memory, but also for imagination, for the creation of novel goals and for spatial navigation.

4. Processing speed is not fixed in the brain; there is no system clock.

Unlike a computer, the human brain has no central clock. Time-keeping in the brain is more like ripples on a pond than a standard digital clock. (To be fair, I should add that some CPUs, known as asynchronous processors, don’t use system clocks.)

5. Short-term memory is not like RAM.

As Chatham writes: “Short-term memory seems to hold only ’pointers’ to long term memory whereas RAM holds data that is isomorphic to that being held on the hard disk.” One advantage of this flexibility of the brain’s short-term memory is that its capacity limit is not fixed: it fluctuates over time, depending on the speed of neural processing, and an individual’s expertise and familiarity with the subject.

6. No hardware/software distinction can be made with respect to the brain or mind.

The tired old metaphor of the mind as the software for the brain’s hardware overlooks the important point that the brain’s cognition is not a purely symbolic process: it requires a physical implementation. Some scientists believe that the inadequacy of the software metaphor for the mind was responsible for the embarrassing failure of symbolic AI.

7. Synapses are far more complex than electrical logic gates.

Because the signals which are propagated along axons are actually electrochemical in nature, they can be modulated in countless different ways, enhancing the complexity of the brain’s processing at each synapse. No computer even comes close to matching this feat.

8. Unlike computers, processing and memory are performed by the same components in the brain.

In Chatham’s words: “Computers process information from memory using CPUs, and then write the results of that processing back to memory. No such distinction exists in the brain.” We can make our memories stronger by the simple act of retrieving them.

9. The brain is a self-organizing system.

Chatham explains:

…[E]xperience profoundly and directly shapes the nature of neural information processing in a way that simply does not happen in traditional microprocessors. For example, the brain is a self-repairing circuit – something known as “trauma-induced plasticity” kicks in after injury. This can lead to a variety of interesting changes, including some that seem to unlock unused potential in the brain (known as acquired savantism), and others that can result in profound cognitive dysfunction…

Chatham argues that failure to take into account the brain’s “trauma-induced plasticity” is having an adverse impact on the emerging field of neuropsychology. A whole science is being stunted by a bad metaphor.

10. Brains have bodies.

Embodiment is a marvelous advantage for a brain. For instance, as Chatham points out, it allows the brain to “off-load” many of its memory requirements onto the body.

I would also add that since computers are physical but not embodied, they lack the built-in teleology of an organism.

As a bonus, Chatham adds an eleventh difference between brains and computers:

11. The brain is much, much bigger than any [current] computer.

Chatham writes:

Accurate biological models of the brain would have to include some 225,000,000,000,000,000 (225 million billion) interactions between cell types, neurotransmitters, neuromodulators, axonal branches and dendritic spines, and that doesn’t include the influences of dendritic geometry, or the approximately 1 trillion glial cells which may or may not be important for neural information processing. Because the brain is nonlinear, and because it is so much larger than all current computers, it seems likely that it functions in a completely different fashion.

Readers may ask why I am taking the trouble to point out the many differences between brains and computers, when both are, after all, physical systems with a finite lifespan. But the point I wish to make is that human beings are debased by Professor Stephen Hawking’s comparison of the human brain to a computer. The brain-computer metaphor is, as we have seen, a very poor one; using it as a rhetorical device to take pot shots at people who believe in immortality is a cheap trick. If Professor Hawking thinks that belief in immortality is scientifically or philosophically indefensible, then he should argue his case on its own merits, instead of resorting to vulgar characterizations.

Why the evolution of the brain is not like the evolution of the skunk’s butt

As we saw above, Professor Jerry Coyne maintains that human intelligence came about through the same mechanism as the skunk’s odoriferous defense. I presume he is talking about the human brain. However, there are solid biological grounds for believing that the brain is the outcome of a radically different kind of process from the one that led to the skunk’s defense system. I would argue that the brain is not the product of an undirected natural process, and that some Intelligence must have directed the evolution of the brain.

Skeptical? I’d like to refer readers to an online article by Steve Dorus et al., entitled, Accelerated Evolution of Nervous System Genes in the Origin of Homo sapiens. (Cell, Vol. 119, 1027–1040, December 29, 2004). Here’s an excerpt:

[T]he evolution of the brain in primates and particularly humans is likely contributed to by a large number of mutations in the coding regions of many underlying genes, especially genes with developmentally biased functions.

In summary, our study revealed the following broad themes that characterize the molecular evolution of the nervous system in primates and particularly in humans. First, genes underlying nervous system biology exhibit higher average rate of protein evolution as scaled to neutral divergence in primates than in rodents. Second, such a trend is contributed to by a large number of genes. Third, this trend is most prominent for genes involved a implicated in the development of the nervous system. Fourth, within primates, the evolution of these genes is especially accelerated in the lineage leading to humans. Based on these themes, we argue that accelerated protein evolution in a large cohort of nervous system genes, which is particularly pronounced for genes involved in nervous system development, represents a salient genetic correlate to the profound changes in brain size and complexity during primate evolution, especially along the lineage leading to Homo sapiens. (Emphases mine – VJT.)

Here’s the link to a press release relating to the same article:

Human cognitive abilities resulted from intense evolutionary selection, says Lahn by Catherine Gianaro, in The University of Chicago Chronicle, January 6, 2005, Vol. 24, no. 7.

University researchers have reported new findings that show genes that regulate brain development and function evolved much more rapidly in humans than in nonhuman primates and other mammals because of natural selection processes unique to the human lineage.

The researchers, led by Bruce Lahn, Assistant Professor in Human Genetics and an investigator in the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, reported the findings in the cover article of the Dec. 29, 2004 issue of the journal Cell.

“Humans evolved their cognitive abilities not due to a few accidental mutations, but rather from an enormous number of mutations acquired through exceptionally intense selection favoring more complex cognitive abilities,” said Lahn. “We tend to think of our own species as categorically different – being on the top of the food chain,” Lahn said. “There is some justification for that.”

From a genetic point of view, some scientists thought human evolution might be a recapitulation of the typical molecular evolutionary process, he said. For example, the evolution of the larger brain might be due to the same processes that led to the evolution of a larger antler or a longer tusk.

“We’ve proven that there is a big distinction. Human evolution is, in fact, a privileged process because it involves a large number of mutations in a large number of genes,” Lahn said.

“To accomplish so much in so little evolutionary time – a few tens of millions of years – requires a selective process that is perhaps categorically different from the typical processes of acquiring new biological traits.” (Emphases mine – VJT.)

Professor Lahn’s remarks on elephants’ tusks apply equally to the evolution of skunk butts. Professor Jerry Coyne’s comparison of the evolution to the evolution of the skunk’s defense system therefore misses the mark. The two cases do not parallel one another.

Finally, here’s an excerpt from another recent science article: Gene Expression Differs in Human and Chimp Brains by Dennis Normile, in “Science” (6 April 2001, pp. 44-45):

“I’m not interested in what I share with the mouse; I’m interested in how I differ from our closest relatives, chimpanzees,” says Svante Paabo, a geneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. Such comparisons, he argues, are the only way to understand “the genetic underpinnings of what makes humans human.” With the human genome virtually in hand, many researchers are now beginning to make those comparisons. At a meeting here last month, Paabo presented work by his team based on samples of three kinds of tissue, brain cortex, liver, and blood from humans, chimps, and rhesus macaques. Paabo and his colleagues pooled messenger RNA from individuals within each species to get rid of intraspecies variation and ran the samples through a microarray filter carrying 20,000 human cDNAs to determine the level of gene expression. The researchers identified 165 genes that showed significant differences between at least two of the three species, and in at least one type of tissue. The brain contained the greatest percentage of such genes, about 1.3%. It also produced the clearest evidence of what may separate humans from other primates. Gene expression in liver and blood tissue is very similar in chimps and humans, and markedly different from that in rhesus macaques. But the picture is quite different for the cerebral cortex. “In the brain, the expression profiles of the chimps and macaques are actually more similar to each other than to humans,” Paabo said at the workshop. The analysis shows that the human brain has undergone three to four times the amount of change in genes and expression levels than the chimpanzee brain… “Among these three tissues, it seems that the brain is really special in that humans have accelerated patterns of gene activity,” Paabo says.” (Emphasis mine – VJT.)

I would argue that these changes that have occurred in the human brain are unlikely to be natural, because of the deleterious effects of most mutations and the extensive complexity and integration of the biological systems that make up the human brain. If anything, this hyper-fast evolution should be catastrophic.

We should remember that the human brain is easily the most complex machine known to exist in the universe. If the brain’s evolution did not require intelligent guidance, then nothing did.

As to when the intelligently directed manipulation of the brain’s evolution took place, my guess would be that it started around 30 million years ago when monkeys first appeared, but became much more pronounced after humans split off from apes around 6 million years ago.

Why the human mind cannot be equated with the human brain

The most serious defect of a materialist account of mind is that it fails to explain the most fundamental feature of mind itself: intentionality. Professor Edward Feser, who has written several books on the philosophy of mind, defines intentionality as “the mind’s capacity to represent, refer, or point beyond itself” (Aquinas, 2009, Oneworld, Oxford, p. 50). For example, when we entertain a concept of something, our mind points at a certain class of things, and it points at the conclusion of an argument when we reason, at some state of affairs when we desire something, and at some person (or animal) when we love someone.

Feser points out that our mental acts – especially our thoughts – typically possess an inherent meaning, which lies beyond themselves. However, brain processes cannot possess this kind of meaning, because physical states of affairs have no inherent meaning as such. Hence our thoughts cannot be the same as our brain processes. As Professor Edward Feser puts it in a recent blog post (September 2008):

Now the puzzle intentionality poses for materialism can be summarized this way: Brain processes, like ink marks, sound waves, the motion of water molecules, electrical current, and any other physical phenomenon you can think of, seem clearly devoid of any inherent meaning. By themselves they are simply meaningless patterns of electrochemical activity. Yet our thoughts do have inherent meaning – that’s how they are able to impart it to otherwise meaningless ink marks, sound waves, etc. In that case, though, it seems that our thoughts cannot possibly be identified with any physical processes in the brain. In short: Thoughts and the like possess inherent meaning or intentionality; brain processes, like ink marks, sound waves, and the like, are utterly devoid of any inherent meaning or intentionality; so thoughts and the like cannot possibly be identified with brain processes.

Four points need to be made here, about the foregoing argument. First, Professor Feser’s argument does not apply to all mental states as such, but to mental acts – specifically, those mental acts (such as thoughts) which possess inherent meaning. My seeing a red patch here now would qualify as a mental state, but since it is not inherently meaningful, it is not covered by Feser’s argument. However, if I think to myself, “That red thing is a tomato” while looking at a red patch, then I am thinking something meaningful. (The reader will probably be wondering, “What about an animal which recognizes a tomato but lacks the linguistic wherewithal to say to itself, ‘This is a tomato’?” Is recognition inherently meaningful? The answer, as I shall argue in part (b) below, depends on whether the animal has a concept of a tomato which is governed by a rule or rules, which it considers normative and tries to follow – e.g. “This red thing is juicy but has no seeds on the inside, so it can’t be a tomato but might be a strawberry; however, that green thing with seeds on the inside could be a tomato.”)

Second, Professor Feser’s formulation of the argument from the intentionality of mental acts is very carefully worded. Some philosophers have suggested that the characteristic feature of mental acts is their “aboutness”: thoughts, arguments, desires and passions in general are about something. But this is surely too vague, as DNA is “about” something too: the proteins it codes for. We can even say that DNA possesses functionality, which is certainly a form of “aboutness.” What it does not possess, however, is inherent meaning, which is a distinctive feature of mental acts. DNA is a molecule that does a job, but it does not and cannot “mean” anything, in and of itself. If (as I maintain) DNA was originally designed, then it was meant by its Designer to do something, but this meaning would be something extrinsic to it. Its functionality, on the other hand, would be something intrinsic to it.

Third, it is extremely difficult to disagree with Feser’s premise that thoughts possess inherent meaning. To do that, one would have to either deny that there are any such things as thoughts, or one would need to locate inherent meaning somewhere else, outside the domain of the mental.

There are a few materialists, known as eliminative materialists, who deny the very existence of mental processes such as thoughts, beliefs and desires. The reason why I cannot take eliminative materialism seriously is that any successful attempt to argue for the truth of eliminative materialism – or, indeed, for the truth of any theory – would defeat eliminative materialism, since argument is, by definition, an attempt to change the beliefs of one’s audience, and eliminative materialism says we have none. If eliminative materialism is true, then argumentation of any kind, about any subject, is always a pointless pursuit, as argumentation is defined as an attempt to change people’s beliefs, and neither attempts not beliefs refer to anything, on an eliminative materialist account.

The other way of arguing against the premise that thoughts possess inherent meaning would be to claim that inherent meaning attaches primarily to something outside the domain of the mental, rather than to our innermost thoughts as we have supposed. But what might this “something” be? The best candidate would be public acts, such as wedding vows, the signing of contracts, initiation ceremonies and funerals. Because these acts are public, one might argue that they are meaningful in their own right. But this will not do. We can still ask: what is it about these acts and ceremonies that makes them meaningful? (A visiting alien might find them utterly meaningless.) And in the end, the only satisfactory answer we can give is: the cultural fact that within our community, we all agree that these acts are meaningful (which presupposes an mental act of assent on the part of each and every one of us), coupled with the psychological fact that the participants are capable of the requisite mental acts needed to perform these acts properly (for instance, someone who is getting married must be capable of understanding the nature of the marriage contract, and of publicly affirming that he/she is acting freely). Thus even an account of meaning which ascribes meaning primarily to public acts still presupposes the occurrence of mental acts which possess meaning in their own right.

Fourth, it should be noted that Professor Feser’s argument works against any materialist account of the mind which identifies mental acts with physical processes (no matter what sort of processes they may be) – regardless of whether this identification is made at the generic (“type-type”) level or the individual (“token-token”) level. The reason is that there is a fundamental difference between mental acts and physical processes: the former possess an inherent meaning, while the latter are incapable of doing so.

Of course, the mere fact that mental acts and physical processes possess mutually incompatible properties does not prove that they are fundamentally different. To use a well-worn example, the morning star has the property of appearing only in the east, while the evening star has the property of appearing only in the west, yer they are one and the same object (the planet Venus). Or again: Superman has the property of being loved by Lois Lane, but Clark Kent does not; yet in the comic book story, they are one and the same person.

However, neither of these examples is pertinent to the case we are considering here, since the meaning which attaches to mental acts is inherent. Hence it must be an intrinsic feature of mental acts, rather than an extrinsic one, like the difference between the morning star and the evening star. As for Superman’s property of being loved by Lois Lane: this is not a real property, but a mere Cambridge property, to use a term coined by the philosopher Peter Geach: in this case, the love inheres in Lois Lane, not Superman. (By contrast, if Superman loves Lois, then the same is also true of Clark Kent. This love is an example of a real property, since it inheres in Superman.)

The difference between mental acts and physical processes does not merely depend on one’s perspective or viewpoint; it is an intrinsic difference, not an extrinsic one. Moreover, it is a real difference, since the property of having an inherent meaning is a real property, and not a Cambridge property. Since mental acts possess a real, intrinsic property which physical processes lack, we may legitimately conclude that mental acts are distinct from physical processes. (Of course, “distinct from” does not mean “independent of”.)

A general refutation of materialism

Feser’s argument can be extended to refute all materialistic accounts of mental acts. Any genuinely materialistic account of mental acts must be capable of explaining them in terms of physical processes. There are only three plausible ways to do this: (a) identifying mental acts with physical processes, (b) showing how mental acts are caused by physical processes, and (c) showing how mental acts are logically entailed by physical processes. No other way of explaining mental acts in terms of physical processes seems conceivable.

The first option, as we have seen, is ruled out: as we saw earlier, mental acts cannot be equated with physical processes, because the former possess inherent meaning as a real, intrinsic property, while the latter do not.

The second option is also impossible, for two reasons. Firstly, if the causal law is to count as a genuine explanation of mental acts, then it must account for their intentionality, or inherent meaningfulness. In other words, we would need a causal law that not only links physical processes to mental acts, but a causal law that links physical processes to meanings. However, meaningfulness is a semantic property, whereas the properties picked out by laws of nature are physical properties. To suppose that there are laws linking physical processes and mental acts, one would have to suppose the existence of a new class of laws of nature: physico-semantic laws.

Secondly, we know for a fact that there are some physical processes (e.g. precipitation) which are incapable of generating meaning: they are inadequate for the task at hand. If we are to suppose that certain other physical processes are capable of generating meaning, then we must believe that these processes are causally adequate for the task of generating meaning, while physical processes such as precipitation are not. But this only invites the further question: why? We might be told that causally inadequate processes lack some physical property (call it F) which causally adequate processes possess – but once again, we can ask: why is physical property F relevant to the task of generating meaning, while other physical properties are not?

So much for the first and second options, then. Mental acts which possess inherent meaning are neither identifiable with physical processes, nor caused by them. The third option is to postulate that mental acts are logically entailed by physical processes. This option is even less promising than the first two: for in order to show that physical processes logically entail mental acts, we would have to show that physical properties logically entail semantic properties. But if we cannot even show that they are causally related, then it will surely be impossible for us to show that they are logically connected. Certainly, the fact that an animal (e.g. a human being) has the property of having a large brain with complex inter-connections that can store a lot of information does not logically entail that this animal – or its brain, or its neural processes, or its bodily movements – has the property of having an inherent meaning.

Hence not only are mental acts distinct from brain processes, but they are incapable of being caused by or logically entailed by brain processes. Since these are the only modes of explanation open to us, it follows that mental acts are incapable of being explained in terms of physical processes.

Let us recapitulate. We have argued that eliminative materialism is false, as well as any version of materialism which identifies mental acts with physical processes, and also any version of materialism in which mental acts supervene upon brain processes (either by being caused by these processes or logically entailed by them). Are there any versions of materialism left for us to consider?

It may be objected that some version of monism, in which one and the same entity has both physical and mental properties, remains viable. Quite so; but monism is not materialism.

We may therefore state the case against materialism as follows:

1. Mental acts are real.

(Denial of this premise entails denying that there can be successful arguments, for an argument is an attempt to change the thoughts and beliefs of the listener, and if there are no mental acts then there are no thoughts and beliefs.)

2. At least some mental acts – e.g. thoughts – are have the real, intrinsic property of being inherently meaningful.

(Justification: it is impossible to account for the meaningfulness of any act, event or process without presupposing the existence of inherently meaningful thoughts.)

3. Physical processes are not inherently meaningful.

4. If process X has a real, intrinsic property F which process Y lacks, then X cannot be identified with Y.

5. By 2, 3 and 4, physical processes cannot be identified with inherently meaningful mental acts.

6. Physical processes are only capable of causing other processes if there is some law of nature linking the former to the latter.

7. Laws of nature are only explanatory of the respective properties they invoke, for the processes they link.

(More precisely: if a law of nature links property F of process X with property G of process Y, then the law explains properties F and G, but not property H which also attaches to process Y. To explain that, one would need another law.)

8. The property of having an inherent meaning is a semantic property.

9. There are not, and there cannot be, laws of nature linking physical properties to semantic properties.

(Justification: No such “physico-semantic” laws have ever been observed; and in any case, semantic properties are not reducible to physical ones.)

10. By 6, 7, 8 and 9, physical processes are incapable of causing inherently meaningful mental acts.

11. Physical processes do not logically entail the occurrence of inherently meaningful mental acts.

12. If inherently meaningful mental acts exist, and if physical processes cannot be identified with them and are incapable of causing them or logically entailing all of them, then materialism is false.

(Justification: materialism is an attempt to account for mental states in physical terms. This means that physical processes must be explanatorily prior to, or identical with, the mental events they purport to explain. Unless physical processes are capable of logically or causally generating mental states, then it is hard to see how they can be said to be capable of explaining them.)

13. Hence by 1, 5, 10, 11 and 12, materialism is false.

Why doesn’t the mind remain sober when the body is drunk?

The celebrated author Mark Twain (1835-1910) was an avowed materialist, as is shown by the following witty exchange he penned:

Old man (sarcastically): Being spiritual, the mind cannot be affected by physical influences?

Young man: No.

Old man: Does the mind remain sober when the body is drunk?

Drunkenness does indeed pose a genuine problem for substance dualism, or the view that mind and body are two distinct things. For even if the mind (which thinks) required sensory input from the body, this would only explain why a physical malady or ailment would shut off the flow of thought. What it would not explain is the peculiar, erratic thinking of the drunkard.

However, the view I am defending here is not Cartesian substance dualism, but a kind of “dual-operation monism”: each of us is one being (a human being), who is capable of a whole host of bodily operations (nutrition, growth, reproduction and movement, as well as sensing and feeling), as well as a few special operations (e.g. following rules and making rational choices) which we perform, but not with our bodies. That doesn’t mean that we perform these acts with some spooky non-material thing hovering 10 centimeters above our heads (a Cartesian soul, which is totally distinct from the body). It just means that not every act performed by a human animal is a bodily act. For rule-following acts, the question, “Which agent did that?” is meaningful; but the question, “Which body part performed the act of following the rule?” is not. Body parts don’t follow rules; people do.

Now, it might be objected that the act of following a rule must be a material act, because we are unable to follow rules when our neuronal firing is disrupted: as Twain pointed out, drunks can’t think straight. But this objection merely shows that certain physical processes in the brain are necessary, in order for rational thought to occur. What it does not show is that these neural processes are sufficient to generate rational thought. As the research of the late Wilder Penfield showed, neurologists’ attempts to produce thoughts or decisions by stimulating people’s brains were a total failure: while stimulation could induce flashbacks and vividly evoke old memories, it never generated thoughts or choices. On other occasions, Penfield was able to make a patient’s arm go up by stimulating a region of his/her brain, but the patient always denied responsibility for this movement, saying: “I didn’t do that. You did.” In other words, Penfield was able to induce bodily movements, but not the choices that accompany them when we act freely.

Nevertheless, the reader might reasonably ask: if the rational act of following a rule is not a bodily act, then why are certain bodily processes required in order for it to occur? For instance, why can’t drunks think straight? The reason, I would suggest, is that whenever we follow an abstract rule, a host of subsidiary physical processes need to take place in the brain, which enable us to recall the objects covered by that rule, and also to track our progress in following the rule, if it is a complicated one, involving a sequence of steps. Disruption of neuronal firing interferes with these subsidiary processes. However, while these neural processes are presupposed by the mental act of following a rule, they do not constitute the rule itself. In other words, all that the foregoing objection shows is that for humans, the act of rule-following is extrinsically dependent on physical events such as neuronal firing. What the objection does not show is that the human act of following or attending to a rule is intrinsically or essentially dependent on physical processes occurring in the brain. Indeed, if the arguments against materialism which I put forward above are correct, the mental act of following a rule cannot be intrinsically dependent on brain processes: for the mental act of following a rule is governed by its inherent meaning, which is something that physical processes necessarily lack.

I conclude, then, that attempts to explain rational choices made by human beings in terms of purely material processes taking place in their brains are doomed to failure, and that whenever we follow a rule (e.g. when we engage in rational thought) our mental act of doing so is an immaterial, non-bodily act.

Implications for immortality

The fact that rational choices cannot be identified with, caused by or otherwise explained by material processes does not imply that we will continue to be capable of making these choices after our bodies die. But what it does show is that the death of the body, per se, does not entail the death of the human person it belongs to. We should also remember that it is in God that we live and move and have our being (Acts 17:28). If the same God who made us wishes us to survive bodily death, and wishes to keep our minds functioning after our bodies have cased to do so, then assuredly He can. And if this same God wishes us to partake of the fullness of bodily life once again by resurrecting our old bodies, in some manner which is at present incomprehensible to us, then He can do that too. This is God’s universe, not ours. He wrote the rules; our job as human beings is to discover them and to follow them, insofar as they apply to our own lives.