Also known as the “warfare thesis.” Sometimes real manuscripts are torn up to manufacture this kind of dreck for gullible tourists and museums:

As I prepared to teach my class ‘Science and Islam’ last spring, I noticed something peculiar about the book I was about to assign to my students. It wasn’t the text – a wonderful translation of a medieval Arabic encyclopaedia – but the cover. Its illustration showed scholars in turbans and medieval Middle Eastern dress, examining the starry sky through telescopes. The miniature purported to be from the premodern Middle East, but something was off.

Besides the colours being a bit too vivid, and the brushstrokes a little too clean, what perturbed me were the telescopes. The telescope was known in the Middle East after Galileo developed it in the 17th century, but almost no illustrations or miniatures ever depicted such an object. When I tracked down the full image, two more figures emerged: one also looking through a telescope, while the other jotted down notes while his hand spun a globe – another instrument that was rarely drawn. The starkest contradiction, however, was the quill in the fourth figure’s hand. Middle Eastern scholars had always used reed pens to write. By now there was no denying it: the cover illustration was a modern-day forgery, masquerading as a medieval illustration.Nir Shafir, “Forging Islamic science” at Aeon

The idea seems to be that we wouldn’t think these people had any science history at all unless it looked like what we might expect. So it’s okay to deceive us.

Here’s another example: In “The Alchemical Revolution,” Sara Reardon (Science 20 May 2011) tells us,

Here’s another example: In “The Alchemical Revolution,” Sara Reardon (Science 20 May 2011) tells us,

A growing number of science historians hold that alchemists—”chymists” is their preferred, less-loaded term—were serious scientists who kept careful lab notes and followed the scientific method as well as any modern researcher and are testing that hypothesis by recreating their experiments. If the alchemists saw what they claimed, these researchers say, then it’s high time for an “alchemical revolution” to restore them to scientific respectability. In the view of these advocates, alchemists have been unjustly ranked with witches and mountebank performers, when in fact they were educated men with limited tools for inquiring into the nature of the universe.

Further to the grudging recent admission at Nature that Christians have funded and done modern science for most of its history*, (You have to pay to read the article.)

* An admission evidently made only for the purpose of trashing Christians for refusal to believe in the latest episode of Darwin Follies – for the same reason as we always knew that Fred Flintstone is a fictional character. Oh, and refusal to believe in crackpot cosmologies, too.

(Note: Al-chemy includes the Arabic “al-”, simply meaning “the chemistry” or “the art of mixing metals.” Many early contributors to chemistry were Arabic-speaking Muslims.)

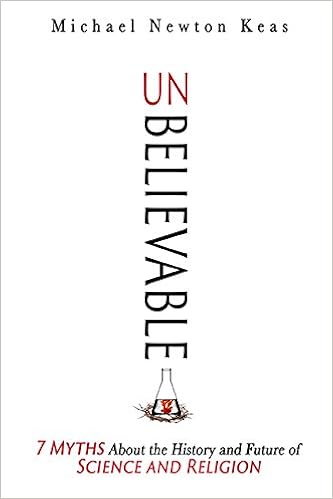

Unbelievable: 7 Myths About the History and Future of Science and Religion by Mike Keas

Of course, fake science history is nothing new and a book has recently been written on it. As David Klinghoffer writes at Evolution News and Science Today:

Praising science as a way to implicitly, or explicitly, club religion over the head is a familiar feature of our culture. It’s not new, either. Mike Keas examines the phenomenon in a forthcoming book, out in November, Unbelievable: Seven Myths About the History and Future of Science and Religion. Rob Crowther chatted with Dr. Keas, a Discovery Institute Senior Fellow, at the recent Insiders Briefing down in Tacoma, a yearly event sponsored by the Center for Science & Culture. More.

But it takes time to get past all the junk.