In a series of recent posts, RDFish has made several penetrating criticisms of the Intelligent Design project, which can be summarized as follows:

(i) the ID project does not currently possess an operational definition of “intelligence” which is genuinely informative and at the same time, suitable for use in scientific research;

(ii) the explanatory filter used by the Intelligent Design community assumes that intelligence is something distinct from law and/or chance – in other words, it commits itself in advance to a belief in contra-casual libertarian free will (the view that when intelligent agents make a decision, they are always capable of acting otherwise), a view which is appealing to “common sense,” but which is highly controversial on both scientific and philosophical grounds;

(iii) the inference to Intelligent Design as an explanation is tantamount to an argument from ignorance: if something cannot be explained by either chance or necessity, it is automatically assumed to be the result of intelligence – a questionable assumption, as there are alternative teleological explanations for the specified complexity that we find in living things, which do not require intelligence;

(iv) any attempt to infer the existence of an Intelligent Designer of the specified complexity that we observe in Nature can be nullified by an equally valid counter-inference: since all of the intelligent designers that we have ever encountered are physical agents which are incapable of thinking in the absence of complex, highly specified, functional interactions between their body parts, we may legitimately conclude that Intelligence can never serve as an Ultimate Explanation for all of the functional specified complexity that we find in Nature. Any Intelligent Designer would have to be a complex, embodied being.

(i) On the definition of “intelligence”

|

The New Caledonian crow is capable of making hooks with its beak, in order to obtain food. Does that make it intelligent? Image courtesy of John Gerrard Keulemans (Catalogue of the Birds in the British Museum) and Wikipedia.

Why it’s not enough to define intelligence in terms of its effects

I put forward a definition of “intelligence” in the final part of my recent post, On not doing one’s homework: A reply to Professor Edward Feser. In that post, I argued that the attempt to define intelligence in terms of the ability to pursue long-term goals, or even to direct suitable means towards those long-term goals, fails to account for one vital feature of intelligence – namely, the fact that it necessarily involves grasping the form, or essential “whatness,” of a thing:

What does it mean for a being to be intelligent? At first, we might attempt to define “intelligence” in terms of one’s ability to pursue goals – especially long-term goals, which require foresight. But the mere ability to pursue goals does not make a being intelligent: even inanimate objects can be said to do that, insofar as they act in certain determinate ways, yet we say that they act blindly and not intelligently. Nor will it do to define “intelligence” as the ability to pursue long-term goals, as such a definition sheds no light on that whereby a being is capable of attaining these goals. One still wants to know: why are some beings capable of pursuing long-term goals, while others are not?

Could we perhaps define intelligence in terms of the ability to direct means towards certain ends? This sounds more promising. In their book, “The Design of Life” (2008, Foundation for Thought and Ethics, Dallas), Professor William Dembski and Dr. Jonathan Wells define “intelligence” as “any cause, agent, or process that achieves and end or goal by employing suitable means or instruments“(page 3), and on page 315, Dembski and Wells define intelligence in more detail, as “A type of cause, process or principle that is able to find, select, adapt, and implement the means needed to effectively bring about ends (or achieve goals or realize purposes). Because intelligence is about matching means to ends, it is inherently teleological.” …

While the attempt to define “intelligence” in terms of means and ends is genuinely illuminating, it still suffers from one defect: it overlooks form… [For example,] a knife is for cutting, but this definition does not tell us whether a knife has only a single handle, or a blade connected to a handle at both ends. Nor does it tell us whether a knife has only a single blade or multiple blades, as a Swiss army knife does. Finally, the cutting function of a knife cannot tell us whether the blade is straight, L-shaped or even D-shaped, as blades with any of these shapes could still cut well enough. The end alone, then, does not determine the form.

Since a thing’s ends do not determine its form, which makes it the kind of thing it is, we must conclude that the ability to grasp a thing’s ends, and even to direct it through various means towards those ends, does not constitute the nature of intelligence as such. For whatever else “intelligence” means, it surely refers to the ability to grasp a thing’s form or its essential “whatness.”

The same criticisms apply to attempts to define “intelligence” as “whatever it is that generates large amounts of functional, complex, specified information.” This definition is at least minimally informative, in that it tells us that something generates the information. But it is, nevertheless, a flawed definition. Defining an activity or process in terms of its effects tells us nothing about what that activity or process is. All it tells us it what the activity or process generates, which isn’t the same thing at all.

Why intelligence cannot be defined in terms of its ability to grasp the forms of natural objects

Accordingly, some philosophers have attempted to define “intelligence” in terms of the mind’s ability to receive or grasp the forms which characterize different kinds of natural objects – a definition which I find unsatisfactory, for reasons that I explained in my recent post:

For the act of understanding a concept cannot simply be defined as the “receiving” of a form – even a universal one. A key feature of concepts is that they are inherently normative. To entertain a concept of a certain kind of thing is to follow a rule which defines how we should think about that kind of thing. For instance, when I refer to a particle as having a positive electric charge, I thereby acknowledge that it has a disposition to attract negatively charged objects and to repel positively charged ones. Those are the rules that define the way we think about positive electric charges, and we agree to follow those rules whenever we talk about electricity. None of the commonly used spatial metaphors for intelligence can capture the act of following a rule.

Thus we cannot define intelligence in terms of an ability to “receive” abstract, universal forms, or to “contain” these forms, or to be in “immediate contact”with these forms, or to “extract” these forms, or to “grasp” these forms. Receiving, containing, touching, extracting and grasping are not rule-following activities as such. They are spatial metaphors for intelligence, but they do not capture its very essence.

Why language is integral to the definition of intelligence

I then argued that any proper definition of “intelligence” has to include the ability to express one’s thoughts in language:

Thirteen years ago, while I was training to be a mathematics teacher, I overheard a teacher explaining to a colleague of hers why she insisted that her students should show their workings when solving a mathematical problem. She remarked: “If they really understand how to solve the problem, then they should be able to explain why they solved the problem in that particular way. If they can’t, then they don’t really understand.” The teacher’s remark struck me as an insightful one. It encapsulates my reasons for being skeptical regarding claims that the much-vaunted tool-making abilities of crows, whose jaw-dropping feats have been in the news lately, demonstrate a capacity for reasoning on their part. It also illustrates that the definition of intelligence is necessarily bound up with the ability to express one’s thoughts in language.

The crucial point here is that the crows are unable to explain the basis of their judgments, as a rational agent should be able to do. The tool-making feats of Betty the crow look impressive, but we cannot ask her: “Why did you make it that way?” as she is incapable of justifying her actions…

What I am proposing in this post is that the act of understanding a natural object can only be characterized by the ability to specify the concept of that object, and the rules that define its form or essence, in language. This specification has to include a complete description of its “whatness” (or substantial form), as well as its built-in “ends” (finality). Not for nothing do we say: “In the beginning was the Word” (John 1:1).

An objection from RDFish: how could we ever be sure that an Intelligent Designer possesses a capacity for language?

|

A diagram illustrating the genetic code, according to the “central dogma”, where DNA ic copied to RNA, which is used to make proteins. Shown here are the first few amino acids for the alpha subunit of hemoglobin. The sixth amino acid (glutamic acid, depicted by the symbol “E”) is mutated in sickle cell anemia versions of the hemoglobin molecule. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

At this point, RDFish raises a very reasonable objection. What scientific evidence could we ever have, he asks, that the Intelligent Designer of life possesses the ability to explain His reasons for acting as he did, using language? The answer, as I wrote in my earlier post, is that we can already find evidence of the Designer’s linguistic abilities within living things themselves: they not only contain a digital code, but programs as well:

If each cell in an organism can be accurately described as running a set of programs, written in various programming languages, then since language is a “signature trait” of intelligent beings, it follows that these phenomena obviously require an Intelligent Being to produce them.

Dr. Stephen Meyer has written extensively about the digital code that we find in living things, in his highly acclaimed book, Signature in the Cell. The existence of digital code in living things points to their having had a Designer Who is capable of using language to describe their essential characteristics. But there’s more.

On April 8, 2010, Dr. Don Johnson, who has both a Ph.D. in chemistry and a Ph.D. in computer and information sciences, gave a presentation entitled Bioinformatics: The Information in Life for the University of North Carolina Wilmington chapter of the Association for Computer Machinery. Dr. Johnson’s presentation is now on-line here. Both the talk and accompanying handout notes can be accessed from Dr. Johnson’s Web page. Dr. Johnson spent 20 years teaching in universities in Wisconsin, Minnesota, California, and Europe. Here’s an excerpt from his presentation blurb:

Each cell of an organism has millions of interacting computers reading and processing digital information using algorithmic digital programs and digital codes to communicate and translate information.

On a slide entitled “Information Systems In Life,” Dr. Johnson points out that:

- the genetic system is a pre-existing operating system;

- the specific genetic program (genome) is an application;

- the native language has a codon-based encryption system;

- the codes are read by enzyme computers with their own operating system;

- each enzyme’s output is to another operating system in a ribosome;

- codes are decrypted and output to tRNA computers;

- each codon-specified amino acid is transported to a protein construction site; and

- in each cell, there are multiple operating systems, multiple programming languages, encoding/decoding hardware and software, specialized communications systems, error detection/correction systems, specialized input/output for organelle control and feedback, and a variety of specialized “devices” to accomplish the tasks of life.

To sum up: the use of the word “program” to describe the workings of the cell is scientifically respectable. It is not just a figure of speech. It is literal.

Intelligent Design theory, then, demonstrates in a striking way how it is possible to speak of the Designer of life and the cosmos as being truly intelligent, in a meaningful sense of the word. Such a Designer can legitimately be described as an Intelligent Being.

Since it is certainly possible for scientists to examine an object and look for evidence that it contains a digital code or a program, I would argue that the foregoing definition of “intelligence” is scientifically workable as well.

Too strong a definition?

|

Chaos Computer Club used a model of the 2001 monolith at the Hackers at Large camp site. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

It might be objected that the definition of “intelligence” which I am proposing is too restrictive, since we can easily identify an object as designed, even in cases when we possess neither a blueprint nor a recipe for the production of that object – which suggests that a demonstration of the Designer’s capacity to use language is not essential to warrant an imputation of design. For example, we can tell that a knife is designed for cutting, just by observing its sharp blade and straight edge, and the oft-cited example of the “monolith on the Moon” in the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey shows that we can confidently identify an object as designed, without knowing anything about the reasons, purposes and intentions of its maker.

In reply, I would point out that the design attribution in the fictional case of the lunar monolith was warranted by virtue of the fact that its dimensions were in the precise ratio of 1 : 4 : 9 (the squares of the first three integers) – an astronomically unlikely outcome for any unguided process. To explain the significance of this ratio, we need to employ the language of mathematics.

As regards the example of the knife: there are mathematical features of a knife blade (e.g. its straightness) which also suggest design. We can then Professor Dembski’s explanatory filter to these features, in order to rule out alternative explanations for these features (law and/or chance). In the case of a knife, the imputation of design is less certain than in the case of the lunar monolith, as there are natural processes which are capable of generating straight edges and sharp blades, whereas there are no known processes which are capable of generating the squares of the first three integers in the dimensions of a block of stone.

“But,” it may be objected, “wouldn’t we still be warranted in ascribing a highly complex arrangement of functional parts to a process of intelligent design, even if we were unable to describe the function of these parts in mathematical terms? Surely we don’t have to know the mathematics behind the optical functioning of the eye, in order to see that it was designed?”

The answer to this objection is that it is the specification that describes the function of the complex system which warrants our imputation of design in instances like these. Because the system possesses specified complexity, its function can be described succinctly, in relatively few words. This linguistic description, when combined with the successful application of Professor Dembski’s explanatory filter, gives us confidence that the system in question was indeed designed. What I would add, however, is that not only the function of the system but also its form (in this case, the arrangement of the parts) must be specifiable in human language, before we can be truly certain that the system was designed. I would also suggest that on some level, the form of an object must be capable of being concisely described, if the object in question is genuinely a designed object.

We can see, then, that the additional “language” requirement which I am proposing is hardly an onerous one, and that systems exhibiting functional specified complexity should be able to satisfy this requirement. A fortiori, we can be all the more certain that an object such as a living cell, whose form can not only be specified in language, but also described in terms of a digital code (encoded in the DNA of all living things) as well as a genetic program (which governs that cell’s development into a mature organism), is indeed a designed object.

(ii) Does Intelligent Design theory commit itself at the outset to a belief in contra-causal libertarian free will?

|

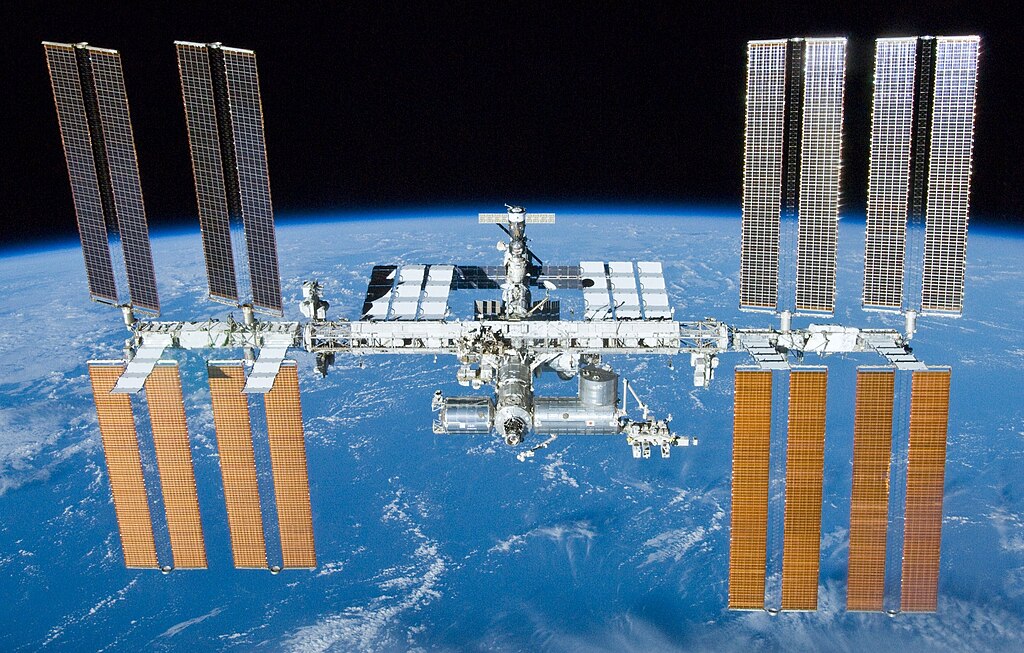

The International Space Station on 23 May 2010, as seen from the departing Space Shuttle Atlantis during space shuttle mission flight STS-132. Barry Arrington has argued, in a post titled, Put Up or Shut Up!, that regardless of whether or not intelligence is reducible to law plus chance, it still possesses certain hallmarks, which enable us to identify it and distinguish it from other processes. He then cited the space station as an example of an object which possesses abundant indicators of having been designed. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

RDFish objects that the explanatory filter used by the Intelligent Design community assumes that intelligence is something distinct from law and/or chance – in other words, it commits itself in advance to a belief in contra-casual libertarian free will. If RDFish had read my 2011 post, The four tiers of Intelligent Design – an ecumenical proposal, he would have seen the solution to his difficulties. In that post, I quoted from an earlier post by Barry Arrington, titled, Put Up or Shut Up!, in which Mr. Arrington argued as follows:

Let us assume for the sake of argument that intelligent agents do NOT have free will, i.e., that the tertium quid does not exist. Let us assume instead, for the sake of argument, that the cause of all activity of all intelligent agents can be reduced to physical causes.

Mr. Arrington contended that even if we make this assumption, for the sake of argument, we can still make legitimate design inferences. As he put it in an earlier post, titled, ID Does Not Posit Supernatural Causes:

For those, such as Aristotle, who believe free will exists, “agency” is a tertium quid (a third thing) beyond chance and necessity. The metaphysical materialist on the other hand must deny the existence of free will. For the materialist, what we perceive as free will or agency is an illusion, the complex interplay of the electro-chemical processes of our brain, which are in turn caused by chance and necessity only.

But the discussion needn’t break down here, because everyone should agree that whether intelligent agents have free will or not, they do in fact leave distinctive indicia of their activities. Did the engineers who designed the space station have free will or where they compelled to design the space station by purely electro-chemical reactions in their brain that can be reduced to the interplay of chance and necessity? For our purposes here it does not matter how one answers this question, because however one answers the question, it is certainly the case that the space station was designed by an intelligent agent. And it is certainly the case that the intelligent agents who designed the space station left indicia of their design by which an observer can distinguish it from asteroids and other satellites of the Earth that were not designed by intelligent agents.

The point is that for our purposes here, we need not argue about whether intelligent agents such as humans have an immaterial free will. Whether free will exists or not, it cannot be reasonably disputed that intelligent agents leave discernible indicia of their activity.

The foregoing passage should suffice to answer RDFish’s objection. Even if one views intelligence as being ultimately the product of law and chance (as materialists do), it still remains the case that intelligent agency has certain distinguishing marks (or indicia) which enable scientists to identify it as such.

In my 2011 post, The four tiers of Intelligent Design – an ecumenical proposal, I also elucidated the role of Professor Dembski’s explanatory filter, by drawing a distinction between proximate and ultimate causes:

At this point, we need to distinguish between proximate and indirect causes, and among indirect causes, we finally need to go back to the ultimate cause. The explanatory filter applies to proximate causes. It can tell us that whatever produced an alien artifact, for instance, must have been an intelligent agent. Likewise, it can tell us that the Being who produced the first living cell in the observable universe must have been intelligent. However, the explanatory filter says nothing about ultimate causes. The explanatory filter alone cannot tell us whether the ultimate cause of a pattern manifesting complex specified information is intelligent or not.

I might observe in passing that as a matter of strict logic, even if “intelligence” were proved to be something distinct from both law and chance, it would not necessarily follow that any entity possessing intelligence would also possess contra-causal free will. For instance, one might view intelligence as some kind of top-down causation, whose activity was determined, but not law-governed. I would like to stress that this is not a view which I take, although I think that animal minds might work in this way. The reason why I mention this possibility is simply to show that the Intelligent Design project does not commit itself at the outset to a particular view of free will – namely, the libertarian view, in which intelligent agents always the possess the power to do otherwise, when they make a choice.

Finally, RDFish may be wondering how one could possibly argue to the existence of a disembodied Intelligence, if Intelligent Design is compatible with materialism. I addressed this objection in my 2011 post, The four tiers of Intelligent Design – an ecumenical proposal:

The claim I am putting forward here is that there are four levels of inquiry in Intelligent Design:

(1) Which patterns in Nature can be identified, through a process of scientific investigation, as the work of intelligent agents? That is, which patterns in Nature can be shown to have intelligent agents as their proximate causes?

(2) Which of the patterns identified in (1) can be shown to have been caused by intelligent agents outside the observable universe?

(3) For which of the patterns identified in (2) as the work of intelligent agents from beyond our universe can scientists rule out chance and/or necessity as the ultimate cause?

(4) Which of the patterns identified in (3) would require an intelligence with an infinite information-generating capacity, and what kind of infinity are we talking about here (aleph-one or higher)?… Now, I would certainly agree … that the laws of physics themselves require an Intelligent Designer, and I have several times argued for [this] view on Uncommon Descent (see here, here and here). This applies to the laws of the multiverse, just as much as it does to the laws of our observable universe. The Designer of these laws would therefore not be constrained by them, and would be able to contravene them if He saw fit to do so. But this is a Level 3 Intelligent Design argument. And it should be clear by now to readers that Barry Arrington’s recent Put Up or Shut Up! post was about Level 1 of Intelligent Design, not Level 2 or 3.

In short: it is only by appealing to the cosmological version of Intelligent Design (i.e. the fine-tuning argument) that we can establish the existence of a disembodied Designer, Who transcends the physical realm, and thereby refute materialism on strictly scientific grounds. I will have more to say below about the legitimacy of the cosmological argument in part (iv) below, where I address RDFish’s argument that any designer must be an embodied agent.

(iii) Are there alternative teleological explanations for the specified complexity we find in living things, apart from intelligent design?

|

The bacterium Proteus mirabilis on an XLD agar plate. Professor James Shapiro, an expert in bacterial genetics who champions a non-Darwinian version of evolution via “natural genetic engineering,” discovered that the gut bacterium Proteus mirabilis forms complex terraced rings, an emergent property of simple rules that the bacterium uses to avoid neighboring cells. Professor Shapiro has also shown that bacteria cooperate in communities which exhibit complex behavior such as hunting, building protective structures and spreading spores, and in which individual bacteria may sacrifice themselves for the benefit of the larger community. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

To his credit, RDFish is no fan of Charles Darwin. Nevertheless, he correctly points out that discrediting Darwin does not suffice to establish the reality of Intelligent Design. Other explanations for the functional specified complexity that we find in living things have also been proposed, and RDFish is particularly impressed with the recent work done by Professor James Shapiro, author of Evolution: A View from the 21st Century (paperback, FT press, 2013). Professor Shapiro summarizes his views in a recent article titled, What Natural Genetic Engineering Does and Does Not Mean (Huffington Post, February 28, 2013):

For me, NGE [Natural Genetic Engineering] is shorthand to summarize all the biochemical mechanisms cells have to cut, splice, copy, polymerize and otherwise manipulate the structure of internal DNA molecules, transport DNA from one cell to another, or acquire DNA from the environment. Totally novel sequences can result from de novo untemplated polymerization or reverse transcription of processed RNA molecules.

NGE describes a toolbox of cell processes capable of generating a virtually endless set of DNA sequence structures in a way that can be compared to erector sets, LEGOs, carpentry, architecture or computer programming…

In summary, NGE encompasses a set of empirically demonstrated cell functions for generating novel DNA structures. These functions operate repeatedly during normal organism life cycles and also in generating evolutionary novelties, as abundantly documented in the genome sequence record.

However, Professor Shapiro was candid enough to admit that the origin of major evolutionary innovations (such as radically new functional arrangements of parts) remains an unsolved problem:

While NGE can help in understanding the molecular details of rapid and widespread genome change, it does not tell us what makes genomic novelties come out to be useful. How natural genetic engineering leads to major new inventions of adaptive use remains a central problem in evolution science.…

To address this problem experimentally, we need to do more ambitious laboratory evolution research looking for complex coordinated changes in the genome.

If we are able to observe cells coordinating NGE functions to make useful complex inventions in real time, major questions arise. How do they perceive what may be useful?… We need to figure out how to do experiments on this.

If experiments show that cells can make distinct appropriate NGE responses to different adaptive challenges, we need to figure out how they do so. This almost certainly would prove to be more than a strictly mechanical process… If such investigations take evolution science into areas that are more than strictly material, so be it. As long as we stay within the realm of natural processes, there are no boundaries on what science can address.

|

The protein hexokinase, as shown in a conventional ball-and-stick molecular model. In its simplest form, which is found in bacteria, this enzyme consists of hundreds of amino acids, which belong to a single domain. The proportion of amino-acid chains with a length of more than 100 units which fold up into a protein that can perform a useful biological function is so low that the odds of finding such a protein via an unguided process, even over billions of years, would be less than the odds of finding a needle in a haystack. To scale in the top right-hand corner are two of the protein’s substrates, ATP and glucose. Image courtesy of Tim Vickers and Wikipedia.

But as Professor William Dembski points out in a critical post titled, Is James Shapiro a Darwinist After All? (Evolution News and Views, January 25, 2012), Shapiro doesn’t go far enough in his questioning of Darwinism. He maintains that non-foresighted processes are sufficient to generate evolutionary novelty. The problem with this view is that non-foresighted processes are by definition incapable of searching for a “needle in a haystack,” which, as Dembski points out, is precisely the kind of search we require, in order to account for the origin of the highly complex proteins which we find in living things, each of which has its own specific function:

Neo-Darwinism essentially localizes the creative potential of evolution in genetic mutations. Shapiro rightly sees that this can’t be the main source of evolutionary variation. So he expands it to include “horizontal DNA transfer, interspecific hybridization, genome doubling and symbiogenesis.” Fine, now you’ve got a richer source of variation. But what is coordinating these variations to bring about the increasing complexity we find in biological systems? Shapiro’s answer is “natural genetic engineering.” Cells, according to Shapiro, are intelligent in that they do their own natural genetic engineering, taking existing structures through horizontal DNA transfer or symbiogenesis, say, and reworking them in new contexts for new uses.

But in making such a claim, has Shapiro really solved anything? Has he truly understood the evolution of any complex biological structures? …

Natural genetic engineering would actually mean something, providing genuine understanding of and solutions for the origin of novel biological structures, if Shapiro could point to actual, identifiable mechanisms and show how they take existing structures and then refashion them into new ones. But Shapiro doesn’t do this…

Shapiro doesn’t know the first thing about how natural genetic engineering itself works. What Shapiro knows is the inputs to evolution. Those inputs are richer than the impoverished inputs of Neo-Darwinism, whose main input is genetic mutation. So Shapiro adds symbiogenesis, lateral gene transfer, etc. We are supposed to be impressed. Okay, it’s great that scientists like Shapiro have been able to discover this enriched set of inputs. And Shapiro claims to have discovered a richer transformative principle for these inputs. Darwin gives us natural selection. Again, this is too impoverished for Shapiro. In its place (or, perhaps, supplementing it), Shapiro gives us natural genetic engineering.

But in fact, natural genetic engineering, in the way Shapiro uses it, is no more enlightening than natural selection, which Shapiro to his credit at least admits is bankrupt. But they’re both magic phrases, mantras that claim to provide insight into how evolutionary transformations occur, but in fact offer no real understanding, nor real solutions. We can see this in Shapiro’s latest reply to Gauger and Axe: “well-documented natural processes are more than adequate to explain how protein evolution for new functionalities can occur in a purely natural and combinatorial fashion.”

Come again? “More than adequate”? Such overblown rhetoric ought immediately to set off warning bells. My colleagues and I would be happy with mere adequacy. The problem is that the natural processes Shapiro cites don’t even rise to that level. To explain protein evolution, it’s not enough to point to some known antecedents (genetic shuffling of one form or another) and then merely invoke the label “natural genetic engineering,” as though this explained anything. Far from explaining what needs to be explained, it sidesteps and misdirects from the real question. This becomes evident when Shapiro cites getting new functionalities in a purely “combinatorial fashion.”

As a probabilist, I’ve had to do my share of combinatorics, a branch of mathematics concerned with counting possibilities. The problem is that in genetics and proteomics, the possible gene and protein products are immense, and so the challenge, always, is to find some biologically meaningful path through these combinatorial spaces. So, when Shapiro invokes natural processes that operate in combinatorial fashion, he is in fact explaining nothing about protein evolution but merely restating the problem.

Intelligent Design: not an argument from ignorance

The problem highlighted by Professor Dembski is not unique to James Shapiro’s theory of natural genetic engineering. It is a problem which besets any account of the origin of astronomically improbable structures with a specified function of their own (such as proteins). Foresight, coupled with an ability to visualize and express to oneself the form of the solution to the problem one is trying to solve, is the only kind of process that is capable of generating structures like these.

Finally, as Dr. Stephen Meyer has pointed out, the argument for an Intelligent Designer is not an argument from ignorance, as RDFish contends, but rather an abductive inference, or an inference to the best explanation. The argument is that we discover certain features in some systems (functional specified complexity) which we know that intelligent beings are capable of generating, by virtue of their ability to conceptualize. By contrast, the unguided processes known to us are extremely unlikely to generate these features within the time available. Given what we know, then, the inference that these features were produced by an intelligent agent is a rational one.

(iv) Is Intelligent Design incapable in principle of taking us to a disembodied Designer?

RDFish’s final objection to ID is that even if Intelligent Design inferences were sometimes warranted, they could never take us to an Intelligent Designer of the cosmos. The reason is that since all of the intelligent designers that we have ever encountered are physical agents which are incapable of thinking in the absence of complex, highly specified, functional interactions between their body parts, it is rational to infer, on the basis of known evidence, that any designer would possess a body instantiating the property of specified complexity. Since this designer would be unable to account for the complexity of its own body, we may conclude that there can, in principle, be no global explanation for functional specified complexity, on the basis of intelligent design. Any Intelligent Design project, then, can, at best, explain only some of the functional specified complexity we find in Nature; there will always be a residue that remains unexplained.

RDFish’s point is that the evidence we have for the proposition that any intelligent designer must be a complex, embodied being is just as powerful as the evidence for the proposition that the functional specified complexity we find in Nature was generated by an intelligent designer. Both propositions are amply confirmed by experience, which teaches us that (i) only intelligent agents are capable of generating highly complex systems which perform a specific function, and that (ii) intelligent agents are incapable of doing anything at all without bodies which function in a complex way. I would like to point out that RDFish is not espousing materialism here: his aim is not to show that mind and body are equivalent, but merely that they are inseparable, in our experience. We have no experience of disembodied minds, just as we have no experience of unguided processes generating highly complex functional systems.

However, I believe that RDFish overlooks a vital point. The evidence that we have for all intelligent agents being embodied is inductive: it is based on a sample of all the intelligent agents known to science – namely, living and dead members of the species Homo sapiens, plus a few species of mammals and birds, if one wishes to be very generous in defining “intelligence.”

By contrast, as I pointed out above, the evidence for Intelligent Design is abductive: it consists in identifying the best explanation for a set of observations which are confirmed by experience and careful testing.

To counter this distinction I have drawn, RDFish would need to formulate an argument, showing that a functioning, complex body constitutes the best possible explanation for an intelligent agent’s ability to think, and to design specified complex systems. That would amount to abductive evidence for RDFish’s claim that intelligent agents require functioning bodies, consisting of multiple parts, in order to be able to think.

The only argument I have seen from RDFish on this point is that many concepts – such as the concept of a protein, or for that matter, the concept of a particular body plan characterizing a certain phylum of complex animals – are inherently complex, and that these concepts require a physical medium of some sort, in order to store the information required to express them.

However, the notion that concepts need to be stored makes sense only for a time-bound designer. A Designer Who is outside space and time would have no need to store His concepts in the first place – and hence, no need to encode them in a physical medium.

In addition, I believe RDFish’s argument makes an illicit slide from the formal complexity of the concepts required by an Intelligent Designer to solve design problems, to the material complexity of the bodily parts possessed by all designers known to us. The formal concepts used by a designer to solve problems are by their nature integral to the design process, whereas the material structures used to represent these concepts are not. There is no reason in principle why a designer would need a complex body in order to solve problems. What a designer really needs are complex concepts. The evidence that all intelligent designers are embodied entities is therefore inductive, rather than abductive.

Nevertheless, RDFish might object that nothing could possibly warrant the claim that the cosmos itself was designed. Put simply, we have no experience of anything outside the cosmos: all of our concepts are derived from objects within the cosmos. If we step outside the very framework which supplies us with our concepts, what hope can we possibly have of reasoning soundly? We should therefore stick to what we do well, and confine ourselves to searching for explanations lying within our own cosmos, rather than beyond it.

The flaw in this argument lies in its Humean assumption that all of our mental concepts are derived from experience. There are, however, certain concepts which the mind constructs and then applies to the objects in our experience – concepts such as “agent,” “explanation,” “cause,” “effect,” “control,” “rule,” “nature,” “capacity” and “goal,” to name just a few. There is nothing illicit in applying these concepts to the cosmos as a whole. For instance, we can meaningfully ask whether the cosmos-as-a-whole had a cause, or whether it requires an explanation. We can also identify rules (laws of Nature) which characterize the cosmos-as-a-whole.

I have argued that we can legitimately infer the existence of a Designer of the cosmos on philosophical grounds from the existence of laws of Nature, in my two posts, Does scientific knowledge presuppose God? A reply to Carroll, Coyne, Dawkins and Loftus and Is God a good theory? A response to Sean Carroll (Part One).

In my post, Is God a good theory? A response to Sean Carroll (Part Two), I explain how the existence of an Intelligent Designer of the cosmos-as-a-whole can be defended on scientific grounds, by appealing to the fine-tuning argument, and why invoking the multiverse fails to undermine this argument. If RDFish wishes to peruse these articles and comment on them, he is welcome to do so.

Finally, I defend the intellectual coherence of a bodiless Designer in my 2011 post, Two pretty good arguments for atheism (courtesy of Dave Mullenix).

I hope this post of mine answers RDFish’s questions, and I would now like to throw the discussion open to readers.