|

|

In February 1987, a supernova appeared in the Southern skies, and remained visible for several months. Giant squid, with their large, powerful eyes, must have seen it, too. But if you believe that the act of perception takes place at the object, as Professor Egnor argues in his perspicacious reply to my last post, then you will have to maintain that the squid’s perception of the stellar explosion took place at the location of the supernova itself: somewhere in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a galaxy about 168,000 light years from Earth. The problem is that the object itself ceased to exist nearly 200 millennia ago, long before the dawn of human history. Even if the squid that witnessed the explosion were capable of having perceptions which are located in intergalactic space, as Egnor contends, they are surely incapable of having perceptions which go back in time.

Before I continue, I would like to compliment Professor Egnor on his latest post, which is nothing less than a literary tour de force. I wish I could write even half as well. The author’s learning and depth of thought are abundantly evident. And although I believe he is wrong, he is at least nobly wrong, for he has succeeded in highlighting a genuine philosophical problem concerning perception: namely, the puzzle of how we can have reliable knowledge of the external world. (Egnor’s original article can be viewed here; see here for my reply.)

Briefly, Egnor contends that even if perception takes place at the location of the sensory organ (a view I defended in my previous post), and not in the subject’s brain, it is still cut off from objects located in the outside world; hence, it can afford us no sure knowledge of the outside world. Additionally, Aristotle’s insistence that perception involves the observer being made like the object she observes, and even possessing this object, only makes sense if the observer makes contact with the object. For these reasons, Egnor holds that his account of perception is the only one which is both true to the teaching of Aristotle and able to explain how we can have genuine knowledge of the external world (bold emphases mine – VJT):

The crux of Aristotle’s theory of perception is that the perceiver “is made like the object and has acquired its quality” (DA II 5)… One is made like an object and acquires its quality by encountering the object, not by watching a movie about the object…

If perception does not occur at the object — if it begins only at the sense organ or the brain — then there is no encounter between perceiver and perceived. If perception begins at the sense organ, and not at the object, then only the sensory stimulus, not the object, is perceived.…

In the Aristotelian view, the perception of an object is the possession of its form. This includes its accidental forms as well as its substantial form. Location is an accidental form (Organon 1b25-2a4). Thus, in my interpretation, possession of an object entails possession of its location — perception of an object occurs at the location of the object.…

There are deeper problems with the notion that perception occurs only at the sense organs and brain. Let us imagine that the Cartesian theater is real and perception occurs only in sense organs and the brain. In this scenario, we only have direct knowledge of our perceptions themselves; we never have direct knowledge of the objects perceived. And in this Cartesian theater, there can be no reliable knowledge of the external world whatsoever, because any attempt at confirmation of knowledge by correlating internal perception with external reality is rendered moot by my inability to perceive the outside world directly. We are trapped inside the theater, and we can’t get out. The Cartesian theater leaves us practically and even theoretically unable to know reality…

And locating perception in the senses, or in the brain and the senses, doesn’t solve the problem, it merely makes the Cartesian theater a little more spacious. Either your knowledge of the world is limited by your skull or it’s limited by your skin. Either way, you’re trapped in solipsism.

Although I made it quite clear in my original post that I reject the notion of a “theater in the brain” where a homunculus views the sensory data which my brain receives, I think it is fair to say that Professor Egnor has exposed a problem with the account I put forward: namely, that it fails to adequately explain how we manage to encounter objects, when we perceive them.

Responding to my objection that the notion of perception occurring at a distance from the observer was simply too bizarre to be true, Professor Egnor proceeds to turn the tables, by pointing out that the Newtonian notion of action at a distance (which scientists came to accept in the seventeenth century) is equally bizarre:

Perception at a distance is no more inconceivable than action at a distance. The notion that a perception of the moon occurs at the moon is “bizarre” (Torley’s word) only if one presumes that perception is constrained by distance and local conditions — perhaps perception would get tired if it had to go to the moon or it wouldn’t be able to go because it’s too cold there. Yet surely the view that the perception of a rose held up to my eye was located at the rose wouldn’t be deemed nearly as bizarre. At what distance does perception of an object at the object become inconceivable?

It is quite true that early theories of gravity and electromagnetism were forced to appeal to the outlandish notion of action at a distance, in order to describe how an object responds to the influence of distant objects. Newton himself had no idea how it could happen, but he famously refused to speculate, writing: “I have not as yet been able to discover the reason for these properties of gravity from phenomena, and I do not feign hypotheses.” Modern physics, however, has dispensed with the need for such a counterintuitive notion, thanks to the development of the concept of a field, which mediates interactions between objects across empty space.

What’s wrong with perception – and action – occurring at a distance from the subject?

In my reply to Egnor’s original article, I did indeed object that the notion of perception taking place at a distance from the observer was a bizarre one; but in addition to that, I put forward a philosophical argument, designed to show that the notion was not only bizarre, but nonsensical. In a nutshell, my argument was that perception is a bodily event, and that an event involving my body cannot take place at a point which is separate from my body. An event involving my body may occur inside my body, or at the surface of my body, but never separately from it. Thus it simply makes no sense to assert that I am here, at point X, but that my perceptions – or for that matter, my actions – are located at an external point Y.

Think of it this way. Suppose that an action or a perception could be spatially divorced from its subject. How could one demonstrate that the action or perception in question – call it A – should be attributed to this subject (Tom), rather than that subject (Mary), who happens to be standing nearby? How would one resolve the matter, if a dispute were to arise as to whose action (or perception) it was?

Again, if we suppose that an action or a perception is capable of being spatially divorced from its subject, then why couldn’t it be temporally divorced as well? Why couldn’t my actions and my perceptions continue, long after I am dead? For that matter, why couldn’t they have taken place before I was even conceived? Professor Egnor’s account of action and perception fails to exclude either of these absurd scenarios.

To my mind, the foregoing objections are absolutely fatal to any philosophical theory which locates the act of perception outside the observer, and at the object itself, even when it is located at some distance from the observer.

Is Professor Egnor’s argument conclusive?

I am a firm believer in the view that when formulating an argument, it is vital to put it forward in the form of a syllogism, so that its validity can be easily assessed. In the absence of a syllogism, the reader is liable to be convinced by the rhetorical force of the argument, rather than its logical force. Accordingly, I have endeavored to reconstruct Professor Egnor’s core argument in logical form, stripping it down to its bare bones:

1. If I am to have direct knowledge of an object when I perceive it, then my perceptions of that object must encounter the object itself – and not an impression, simulation or representation of it.

2. In order for my perceptions to encounter an object, my perceptions must come into immediate contact with it.

3. Some objects which I perceive are spatially distant from my body.

4. Hence, if I am to have direct knowledge of these distant objects when I perceive them, then my perceptions of these objects must (somehow) come into immediate contact with them.

5. But my body does not come into immediate contact with these distant objects, when I perceive them.

6. Hence my perceptions of distant objects cannot be located on or inside my body, but must be located outside my body, at the objects themselves.

At first sight, the argument appears unexceptionable, when couched in this form. However, some of the key terms used in the argument turn out to be rather vague and ill-defined. For instance: I know perfectly well what it means for me to encounter an object, but what does it mean for my perceptions to encounter an object (as stated in premises 1 and 2)? That strikes me as an odd way of talking.

One possible remedy for this problem would be to replace “my perceptions” with “I” in the first two premises. But if we simply say that perception simply requires me to encounter (and come into contact with) the objects I perceive, then we run into trouble in premise 3, which states the rather obvious fact that I don’t come into contact with all of the objects I perceive.

A critic of Egnor’s argument might be inclined to reject premise 2. After all, if Professor Egnor is willing to entertain the thought that the direct perception of an object can be spatially distant from the perceiving subject, then why can’t a direct perception of an object be spatially distant from the perceiving object, as well? If the former is conceivable, then why not the latter?

Or perhaps we should reject premise 1, instead. Why should it be the case that my direct perceptions of an object have to encounter the object? Surely it is I who encounter the object, via my perceptions of it.

At this point, I am reminded of Fred Dretske’s aphorism, “One man’s modus ponens is another man’s modus tollens.”

How the Krakatoa eruption undercuts the corpuscular theory of perception

|

|

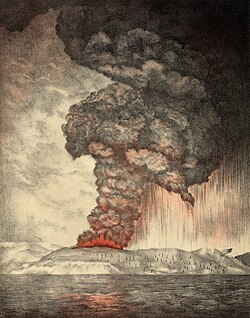

However, in this Christmas season, I do not wish to be accused of being uncharitable in my reading of Professor Egnor’s argument. So I’d like to use another analogy, in order to bring out the point which Egnor wants to make. Most readers will be familiar with the volcanic eruption which took place in Indonesia in 1883, destroying most of the island of Krakatoa as well as its surrounding archipelago.

Now, suppose that I had lived about 100 kilometers from the island, at the time of the eruption. In that case, it would have been too far away for me to have actually seen the island exploding, with my own eyes. However, I would certainly have heard a loud noise – the sound of the explosion was heard even 3,000 miles away, in Alice Springs, Australia – and in addition to that, I would have been inundated with particles of volcanic ash from the eruption. Let’s put aside my perception of the sound of the explosion. The question I’d like to focus on is: does my being inundated with particles of volcanic ash count as a perception of the explosion?

The reason why I am posing this question is that it has bearing on what I’ll call the corpuscular theory of perception, which was defended by Cartesians and by atomists in the seventeenth century, and which is still upheld by modern philosophers. On this account, what happens when I perceive a distant body, such as the supernova which was seen to explode in 1987, is that particles (or corpuscles) travel from that object to my eye – rather like the way in which particles of volcanic ash traveled from the Krakatoa explosion to people living in surrounding areas. In the 21st century, we refer to these “particles” as photons of light, but the basic idea is the same as it was in the seventeenth century.

Getting back to Krakatoa: if I had been inundated with particles of ash from the Krakatoa eruption back in 1883, what could I have concluded from that fact? Nothing much, really. All that I could have said was that something had caused those particles to reach me, but I would have had absolutely no idea what it was. My being rained on with particles of ash could hardly qualify as a perception of the eruption itself: being situated at some distance from the eruption, I would have been unable to conclude that an eruption had even occurred. All I could have concluded was: “Something big happened.”

The above example, I believe, serves to illustrate the point Professor Egnor is making, in his critique of theories of perception which locate the act of perception away from the object itself, and either at or in the body of the observer. For what Egnor is arguing is that if these theories are correct, then I am in a similar quandary when I perceive distant objects: all I can say is that “something I know not what” is causing my perceptions. There is no real encounter between the observer and the observed.

An irenic proposal: it is objects which reach out to us, not we to them

At this point, I’d like to make an irenic proposal to Professor Egnor. He has indeed highlighted a genuine philosophical problem when he argues that any veridical perception of an object requires an encounter between the perceiver and the object itself, and he is also correct in saying that corpuscular theories of perception fail to do justice to this encounter. What I’d like to suggest is that instead of supposing (as Egnor does) that my act of perception of a distant object takes place at the distant object itself, which I somehow “reach out to” when I perceive its form, wouldn’t it be more sensible to suppose that it is the object which reaches out to me, when I perceive it?

In other words, what I am saying is that when I perceive a distant star by means of photons emitted from that star impinging on my eye, something is happening which is very different in character from my getting rained on by particles of volcanic ash from the Krakatoa eruption. The vital difference is that the particles of ash failed to manifest the character of the object itself to me: unless I had been a trained geologist, I would have been in no position to know that they came from a volcano, rather than (say) a meteorite. When I perceive a star, on the other hand, photons emitted by that star (many years ago) enter my eye and modify the organ itself, in a way which literally gives me a picture of their source. Looking at the star, I can determine that it is located in a certain region of the sky, that it is highly luminous, and that it is of a certain color. Looking at it through a telescope, I can further determine that it is roughly round in shape. And if the star in question is sufficiently close to Earth, I can even directly calculate its distance, using the method of parallax, and I can also compute its size.

What makes my perceptions both genuine and reliable in this case is that the star, in its act of emitting photons, does something much more than merely projecting particles: it also projects its own powers – in this case, the power to illuminate observers, in a particular way. And when I am affected by the star’s powers, I am thereby informed (literally, “in-formed”) in a manner which enables me to have a veridical perception of the star itself, and to arrive at a genuine knowledge of what it is.

We can now make sense of Aristotle’s statement that in the act of perception, the observer “is made like the object and has acquired its quality” (De Anima II 5), as well as his claim that the perception of an objection entails having a possession of its form. For when I perceive a distant star, I do indeed receive its form, by virtue of my eye’s being affected by the normal exercise of its powers: the star is the kind of object which has a tendency to emit light of a certain wavelength, which we perceive as “red.” Because the star is exercising its normal, regular powers when it affects me in this way, I am able to recognize that one of its characteristics is to appear red, and that another of its characteristics is to shine. I also perceive its position in the sky, and because “the stars in their courses” appear to follow a regular path in the night sky, I know that the star I perceive is not a phosphorescent flash caused by a random disturbance of my optic nerve, but an object, with a well-defined location, shape, color and size.

But, it will be asked, how can a distant object project its powers to an observer? The notion seems a little mysterious. I would suggest that the modern scientific concept of a field (which I mentioned above) may go some way towards dispelling this mystery. Briefly, the idea is that every material object is surrounded by a field of some sort – gravitational, electromagnetic, strong, weak, or what have you. We can never divorce an object from its surrounding field: the two go together like hand and glove. What I am saying is that the field serves to project the object itself: when the object’s field interacts with another body (such as the body of an observer), that body is then subjected to (and affected by) the powers of the object. The effect is not instantaneous; it takes a certain interval of time. But that is unimportant. What matters is that to perceive an object is to fall under its powers, in some way, and to thereby be informed by it, when one’s sensory organs are altered by the normal exercise of those powers.

The key difference between Egnor’s account of perception and mine, then, is that in his account, it is we who reach out to the object, when we perceive it; whereas on my account, it is the object which reaches out to us. And in the case of an exploding star, the object is capable of reaching out to us even after it has ceased to exist, because the photons it projects continue traveling in space, long after it is gone. Objects can thus exercise their powers in remote locations, even when they are no more.

One might ask: is this a case of the star’s actions being temporally divorced from the star itself – a notion which I rejected as absurd in my philosophical argument against the possibility of actions or perceptions being either spatially or temporally divorced from their subject? There is indeed a temporal delay between the action and its effect – just as there would be if a fiend were to plot a murder by enclosing a bomb inside his last will and testament, which was designed to detonate only when it was opened, some time after his death. But even in this case, the dastardly deed of enclosing the bomb inside the will is performed during the lifetime of the fiend – and similarly, the action of emitting light is performed during the lifetime of the star, even its effects are only felt by us much later. Thus there is no “temporal divorce” between the entity and its actions, but only between the actions and their effects.

It seems to me that the account of perception which I am defending here is a lot less odd, metaphysically speaking, than the account put forward by Professor Egnor. It also appears to accord better with common sense. But at this point, I shall lay down my pen, and let my readers judge the matter for themselves. I am also happy to let Professor Egnor have the last word in this exchange, and I would like to wish him a merry Christmas.

What do readers think?

UPDATE: Over at ENV, Professor Egnor has written a reply to my post, on which I have briefly commented below (see here).