This is a very complex subject, so as usual I will try to stick to the essentials to make things as clear as possible, while details can be dealt with in the discussion.

It is difficult to define exactly the role of the Ubiquitin System. It is usually considered mainly a pathway which regulates protein degradation, but in reality its functions are much wider than that.

In essence, the US is a complex biological system which targets many different types of proteins for different final fates.

The most common “fate” is degradation of the protein. In that sense, the Ubiquitin System works together with another extremely complex cellular system, the proteasome. In brief, the Ubiquitin System “marks” proteins for degradation, and the proteasome degrades them.

It seems simple. It is not.

Ubiquitination is essentially one of many Post-Translational modifications (PTMs): modifications of proteins after their synthesis by the ribosome (translation). But, while most PTMs use simpler biochemical groups that are usually added to the target protein (for example, acetylation), in ubiquitination a whole protein (ubiquitin) is used as a modifier of the target protein.

The tool: Ubiquitin

Ubiquitin is a small protein (76 AAs). Its name derives from the simple fact that it is found in most tissues of eukaryotic organisms.

Here is its aminoacid sequence:

MQIFVKTLTGKTITLEVEPSDTIENVKAKIQDKEGIPPD

QQRLIFAGKQLEDGRTLSDYNIQKESTLHLVLRLRGG

Essentially, it has two important properties:

- As said, it is ubiquitous in eukaryotes

- It is also extremely conserved in eukaryotes

In mammals, ubiquitin is not present as a single gene. It is encoded by 4 different genes: UBB, a poliubiquitin (3 Ub sequences); UBC, a poliubiquitin (9 Ub sequences); UBA52, a mixed gene (1 Ub sequence + the ribosomal protein L40); and RPS27A, again a mixed gene (1 Ub sequence + the ribosomal protein S27A). However, the basic ubiquitin sequence is always the same in all those genes.

Its conservation is one of the highest in eukaryotes. The human sequence shows, in single celled eukaryotes:

Naegleria: 96% conservation; Alveolata: 100% conservation; Cellular slime molds: 99% conservation; Green algae: 100% conservation; Fungi: best hit 100% conservation (96% in yeast).

Ubiquitin and Ubiquitin like proteins (see later) are characterized by a special fold, called β-grasp fold.

The semiosis: the ubiquitin code

The title of this OP makes explicit reference to semiosis. Let’s try to see why.

The simplest way to say it is: ubiquitin is a tag. The addition of ubiquitin to a substrate protein marks that protein for specific fates, the most common being degradation by the proteasome.

But not only that. See, for example, the following review:

Nonproteolytic Functions of Ubiquitin in Cell Signaling

Abstract:

The small protein ubiquitin is a central regulator of a cell’s life and death. Ubiquitin is best known for targeting protein destruction by the 26S proteasome. In the past few years, however, nonproteolytic functions of ubiquitin have been uncovered at a rapid pace. These functions include membrane trafficking, protein kinase activation, DNA repair, and chromatin dynamics. A common mechanism underlying these functions is that ubiquitin, or polyubiquitin chains, serves as a signal to recruit proteins harboring ubiquitin-binding domains, thereby bringing together ubiquitinated proteins and ubiquitin receptors to execute specific biological functions. Recent advances in understanding ubiquitination in protein kinase activation and DNA repair are discussed to illustrate the nonproteolytic functions of ubiquitin in cell signaling.

Another important aspect is that ubiquitin is not one tag, but rather a collection of different tags. IOWs, a tag based code.

See, for example, here:

The Ubiquitin Code in the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System and Autophagy

(Paywall).

Abstract:

The conjugation of the 76 amino acid protein ubiquitin to other proteins can alter the metabolic stability or non-proteolytic functions of the substrate. Once attached to a substrate (monoubiquitination), ubiquitin can itself be ubiquitinated on any of its seven lysine (Lys) residues or its N-terminal methionine (Met1). A single ubiquitin polymer may contain mixed linkages and/or two or more branches. In addition, ubiquitin can be conjugated with ubiquitin-like modifiers such as SUMO or small molecules such as phosphate. The diverse ways to assemble ubiquitin chains provide countless means to modulate biological processes. We overview here the complexity of the ubiquitin code, with an emphasis on the emerging role of linkage-specific degradation signals (degrons) in the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and the autophagy-lysosome system (hereafter autophagy).

A good review of the basics of the ubiquitin code can be found here:

(Paywall)

It is particularly relevant, from an ID point of view, to quote the starting paragraph of that paper:

When in 1532 Spanish conquistadores set foot on the Inca Empire, they found a highly organized society that did not utilize a system of writing. Instead, the Incas recorded tax payments or mythology with quipus, devices in which pieces of thread were connected through specific knots. Although the quipus have not been fully deciphered, it is thought that the knots between threads encode most of the quipus’ content. Intriguingly, cells use a regulatory mechanism—ubiquitylation—that is reminiscent of quipus: During this reaction, proteins are modified with polymeric chains in which the linkage between ubiquitin molecules encodes information about the substrate’s fate in the cell.

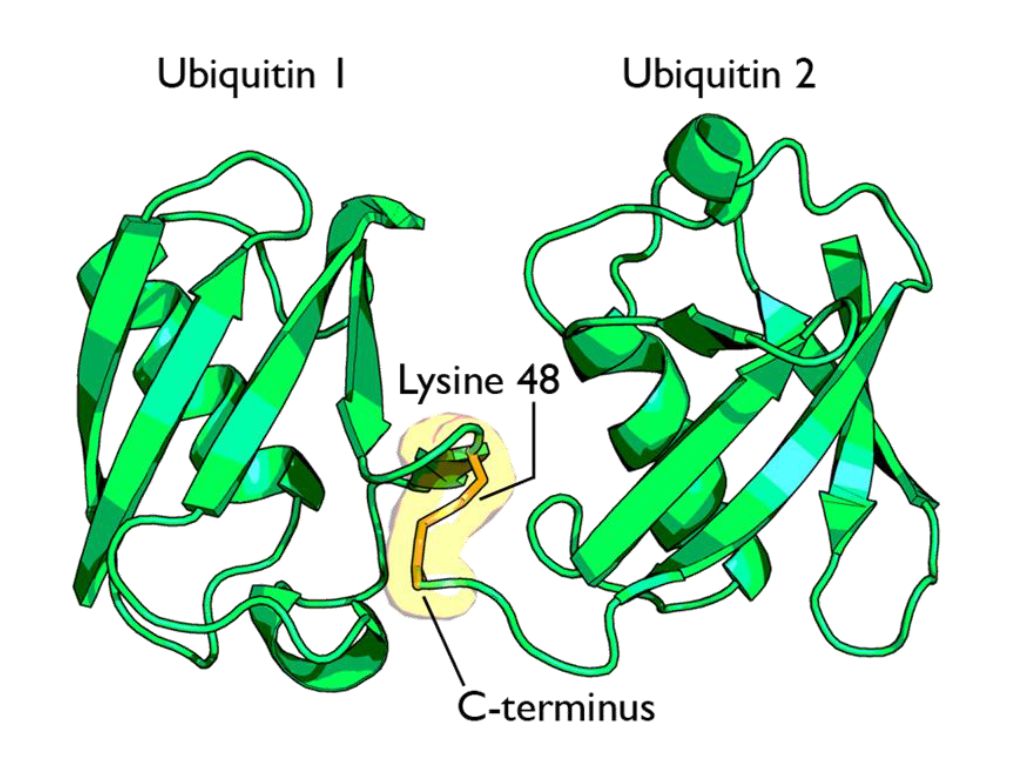

Now, ubiquitin is usually linked to the target protein in chains. The first ubiquitin molecule is covalently bound through its C-terminal carboxylate group to a particular lysine, cysteine, serine, threonine or N-terminus of the target protein.

Then, additional ubiquitins are added to form a chain, and the C-terminus of the new ubiquitin is linked to one of seven lysine residues or the first methionine residue on the previously added ubiquitin.

IOWs, each ubiquitin molecule has seven lysine residues:

K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63

And one N terminal methionine residue:

M1

And a new ubiquitin molecule can be added at each of those 8 sites in the previous ubiquitin molecule. IOWs, those 8 sites in the molecule are configurable switches that can be used to build ubiquitin chains.

Her are the 8 sites, in red, in the ubiquitin molecule:

MQIFVKTLTGKTITLEVEPSDTIENVKAKIQDKEGIPPD

QQRLIFAGKQLEDGRTLSDYNIQKESTLHLVLRLRGG

Fig 1 shows two ubiquitin molecules joined at K48.

The simplest type of chain is homogeneous (IOWs, ubiquitins are linked always at the same site). But many types of mixed and branched chains can also be found.

Let’s start with the most common situation: a poli-ubiquitination of (at least) 4 ubiqutins, linearly linked at K48. This is the common signal for proteasome degradation.

By the way, the 26S proteasome is another molecular machine of incredible complexity, made of more than 30 different proteins. However, its structure and function are not the object of this OP, and therefore I will not deal with them here.

The ubiquitin code is not completely understood, at present, but a few aspects have been well elucidated. Table 1 sums up the most important and well known modes:

Code |

Meaning |

| Polyubiquitination (4 or more) with links at K48 or at K11 | Proteasomal degradation |

| Monoubiqutination (single or multiple) | Protein interactions, membrane trafficking, endocytosis |

| Polyubiquitination with links at K63 | Endocytic trafficking, inflammation, translation, DNA repair. |

| Polyubiquitination with links at K63 (other links) | Autophagic degradation of protein substrates |

| Polyubiquitination with links at K27, K29, K33 | Non proteolytic processes |

| Rarer chain types (K6, K11) | Under investigation |

However, this is only a very partial approach. A recent bioinformatics paper:

An Interaction Landscape of Ubiquitin Signaling

(Paywall)

Has attempted for the first time a systematic approach to deciphering the whole code, using synthetic diubiquitins (all 8 possible variants) to identify the different interactors with those signals, and they identified, with two different methodologies, 111 and 53 selective interactors for linear polyUb chains, respectively. 46 of those interactors were identified by both methodologies.

The translation

But what “translates” the complex ubiquitin code, allowing ubiquinated proteins to met the right specific destiny? Again, we can refer to the diubiquitin paper quoted above.

How do cells decode this ubiquitin code into proper cellular responses? Recent studies have indicated that members of a protein family, ubiquitin-binding proteins (UBPs), mediate the recognition of ubiquitinated substrates. UBPs contain at least one of 20 ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) functioning as a signal adaptor to transmit the signal from ubiquitinated substrates to downstream effectors

But what are those “interactors” identified by the paper (at least 46 of them)? They are, indeed, complex proteins which recognize specific configurations of the “tag” (the ubiquitin chain), and link the tagged (ubiquinated) protein to other effector proteins which implement its final fate, or anyway contribute in deffrent forms to that final outcome.

The basic control of the procedure: the complexity of the ubiquitination process.

So, we have seen that ubiquitin chains work as tags, and that their coded signals are translated by specific interactors, so that the target protein may be linked to its final destiny, or contribute to the desired outcome. But we must still address one question: how is the ubiquitination of the different target proteins implemented? IOWs, what is the procedure that “writes” the specific codes associated to specific target proteins?

This is indeed the first step in the whole process. But it is also the most complex, and that’s why I have left it for the final part of the discussion.

Indeed, the ubiquitination process needs to realize the following aims:

- Identify the specific protein to be ubiquitinated

- Recognize the specific context in which that protein needs to be ubiquitinated

- Mark the target protein with the correct tag for the required fate or outcome

We have already seen that the ubiquitin system is involved in practically all different cellular paths and activities, and therefore we can expect that the implementation of the above functions must be a very complex thing.

And it is.

Now, we can certainly imagine that there are many different layers of regulation that may contribute to the general control of the procedure, specifically epigenetic levels, which are at present poorly understood. But there is one level that we can more easily explore and understand, and it is , as usual, the functional complexity of the proteins involved.

And, even at a first gross analysis, it is really easy to see that the functional complexity implied by this process is mind blowing.

Why? It is more than enough to consider the huge number of different proteins involved. Let’s see.

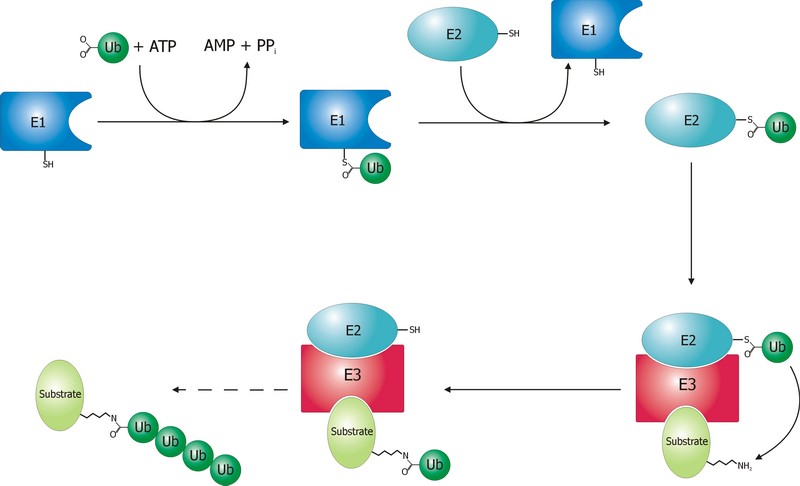

The ubiquitination process is well studied. It can be divided into three phases, each of which is implemented by a different kind of protein. The three steps, and the three kinds of proteins that implement them, take the name of E1, E2 and E3.

The E1 step of ubiquitination.

This is the first thing that happens, and it is also the simplest.

E1 is the process of activation of ubiquitin, and the E1 proteins is called E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme. To put it simply, this enzyme “activates” the ubiquitin molecule in an ATP dependent process, preparing it for the following phases and attaching it to its active site cysteine residue. It is not really so simple, but for our purposes that can be enough.

This is a rather straightforward enzymatic reaction. In humans there are essentially two forms of E1 enzymes, UBA1 and UBA6, each of them about 1000 AAs long, and partially related at sequence level (42%).

The E2 step of ubiquitination.

The second step is ubiquitin conjugation. The activated ubiquitin is transferred from the E1 enzyme to the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, or E2 enzyme, where it is attached to a cysteine residue.

This apparently simple “transfer” is indeed a complex intermediate phase. Humans have about 40 different E2 molecules. The following paper:

E2 enzymes: more than just middle men

details some of the functional complexity existing at this level.

Abstract:

Ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2s) are the central players in the trio of enzymes responsible for the attachment of ubiquitin (Ub) to cellular proteins. Humans have ∼40 E2s that are involved in the transfer of Ub or Ub-like (Ubl) proteins (e.g., SUMO and NEDD8). Although the majority of E2s are only twice the size of Ub, this remarkable family of enzymes performs a variety of functional roles. In this review, we summarize common functional and structural features that define unifying themes among E2s and highlight emerging concepts in the mechanism and regulation of E2s.

However, I will not go into details about these aspects, because we have better things to do: we still have to discuss the E3 phase!

The E3 step of ubiquitination.

This is the last phase of ubiquitination, where the ubiquitin tag is finally transferred to the target protein, as initial mono-ubiquitination, or to build an ubiquitin chain by following ubiqutination events. The proteins which implement this final passage are call E3 ubiquitin ligases. Here is the definition from Wikipedia:

A ubiquitin ligase (also called an E3 ubiquitin ligase) is a protein that recruits an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme that has been loaded with ubiquitin, recognizes a protein substrate, and assists or directly catalyzes the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to the protein substrate.

It is rather obvious that the role of the E3 protein is very important and delicate. Indeed it:

- Recognizes and links the E2-ubiquitin complex

- Recognizes and links some specific target protein

- Builds the appropriate tag for that protein (Monoubiquitination, mulptiple monoubiquitination, or poliubiquitination with the appropriate type of ubiquitin chain).

- And it does all those things at the right moment, in the right context, and for the right protein.

IOWs, the E3 protein writes the coded tag. It is, by all means, the central actor in our complex story.

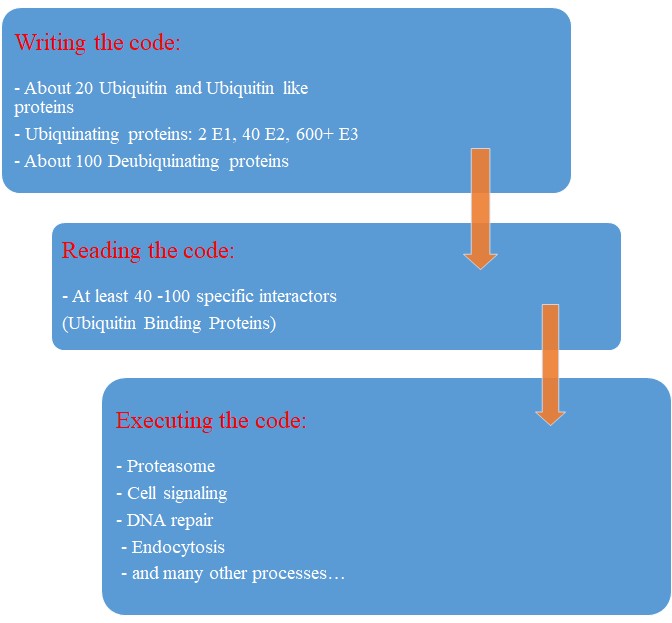

So, here comes the really important point: how many different E3 ubiquitin ligases do we find in eukaryotic organisms? And the simple answer is: quite a lot!

Humans are supposed to have more than 600 different E3 ubiquitin ligases!

So, the human machinery for ubiquitination is about:

2 E1 proteins – 40 E2 proteins – >600 E3 proteins

A real cascade of complexity!

OK, but even if we look at single celled eukaryotes we can already find an amazing level of complexity. In yeast, for example, we have:

1 or 2 E1 proteins – 11 E2 proteins – 60-100 E3 proteins

See here:

The Ubiquitin–Proteasome System of Saccharomyces cerevisiae

Now, a very important point. Those 600+ E3 proteins that we find in humans are really different proteins. Of course, they have something in common: a specific domain.

From that point of view, they can be roughly classified in three groups according to the specific E3 domain:

- RING group: the RING finger domain ((Really Interesting New Gene) is a short domain of zinc finger type, usually 40 to 60 amino acids. This is the biggest group of E3s (about 600)

- HECT domain (homologous to the E6AP carboxyl terminus): this is a bigger domain (about 350 AAs). Located at the C terminus of the protein. It has a specific ligase activity, different from the RING In humans we have approximately 30 proteins of this type.

- RBR domain (ring between ring fingers): this is a common domain (about 150 AAs) where two RING fingers are separated by a region called IBR, a cysteine-rich zinc finger. Only a subset of these proteins are E3 ligases, in humans we have about 12 of them.

See also here.

OK, so these proteins have one of these three domains in common, usually the RING domain. The function of the domain is specifically to interact with the E2-ubiquitin complex to implement the ligase activity. But the domain is only a part of the molecule, indeed a small part of it. E3 ligases are usually big proteins (hundreds, and up to thousands of AAs). Each of these proteins has a very specific non domain sequence, which is probably responsible for the most important part of the function: the recognition of the specific proteins that each E3 ligase processes.

This is a huge complexity, in terms of functional information at sequence level.

Our map of the ubiquinating system in humans could now be summarized as follows:

2 E1 proteins – 40 E2 proteins – 600+ E3 proteins + thousands of specific substrates

IOWs, each of hundreds of different complex proteins recognizes its specific substrates, and marks them with a shared symbolic code based on uniquitin and its many possible chains. And the result of that process is that proteins are destined to degradation by the proteasome or other mechanisms, and that protein interactions and protein signaling are regulated and made possible, and that practically all cellular functions are allowed to flow correctly and smoothly.

Finally, here are two further compoments of the ubuquitination system, which I will barely mention, to avoid making this OP too long.

Ubiquitin like proteins (Ubl):

A number of ubiquitin like proteins add to the complexity of the system. Here is the abstract from a review:

The eukaryotic ubiquitin family encompasses nearly 20 proteins that are involved in the posttranslational modification of various macromolecules. The ubiquitin-like proteins (UBLs) that are part of this family adopt the β-grasp fold that is characteristic of its founding member ubiquitin (Ub). Although structurally related, UBLs regulate a strikingly diverse set of cellular processes, including nuclear transport, proteolysis, translation, autophagy, and antiviral pathways. New UBL substrates continue to be identified and further expand the functional diversity of UBL pathways in cellular homeostasis and physiology. Here, we review recent findings on such novel substrates, mechanisms, and functions of UBLs.

These proteins include SUMO, Nedd8, ISB15, and many others.

Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs):

The process of ubiquitination, complex as it already is, is additionally regulated by these enzymes which can cleave ubiquitin from proteins and other molecules. Doing so, they can reverse the effects of ubiquitination, creating a delicately balanced regulatory network. In humans there are nearly 100 DUB genes, which can be classified into two main classes: cysteine proteases and metalloproteases.

By the way, here is a beautiful animation of the basic working of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in degrading damaged proteins:

A summary:

So, let’s try a final graphic summary of the whole ubiquitin system in humans:

Evolution of the Ubiquitin system?

The Ubiqutin system is essentially an eukaryotic tool. Of course, distant precursors for some of the main components have been “found” in prokaryotes. Here is the abstract from a paper that sums up what is known about the prokaryotic “origins” of the system:

Structure and evolution of ubiquitin and ubiquitin-related domains.

(Paywall)

Abstract:

Since its discovery over three decades ago, it has become abundantly clear that the ubiquitin (Ub) system is a quintessential feature of all aspects of eukaryotic biology. At the heart of the system lies the conjugation and deconjugation of Ub and Ub-like (Ubls) proteins to proteins or lipids drastically altering the biochemistry of the targeted molecules. In particular, it represents the primary mechanism by which protein stability is regulated in eukaryotes. Ub/Ubls are typified by the β-grasp fold (β-GF) that has additionally been recruited for a strikingly diverse range of biochemical functions. These include catalytic roles (e.g., NUDIX phosphohydrolases), scaffolding of iron-sulfur clusters, binding of RNA and other biomolecules such as co-factors, sulfur transfer in biosynthesis of diverse metabolites, and as mediators of key protein-protein interactions in practically every conceivable cellular context. In this chapter, we present a synthetic overview of the structure, evolution, and natural classification of Ub, Ubls, and other members of the β-GF. The β-GF appears to have differentiated into at least seven clades by the time of the last universal common ancestor of all extant organisms, encompassing much of the structural diversity observed in extant versions. The β-GF appears to have first emerged in the context of translation-related RNA-interactions and subsequently exploded to occupy various functional niches. Most biochemical diversification of the fold occurred in prokaryotes, with the eukaryotic phase of its evolution mainly marked by the expansion of the Ubl clade of the β-GF. Consequently, at least 70 distinct Ubl families are distributed across eukaryotes, of which nearly 20 families were already present in the eukaryotic common ancestor. These included multiple protein and one lipid conjugated forms and versions that functions as adapter domains in multimodule polypeptides. The early diversification of the Ubl families in eukaryotes played a major role in the emergence of characteristic eukaryotic cellular substructures and systems pertaining to nucleo-cytoplasmic compartmentalization, vesicular trafficking, lysosomal targeting, protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum, and chromatin dynamics. Recent results from comparative genomics indicate that precursors of the eukaryotic Ub-system were already present in prokaryotes. The most basic versions are those combining an Ubl and an E1-like enzyme involved in metabolic pathways related to metallopterin, thiamine, cysteine, siderophore and perhaps modified base biosynthesis. Some of these versions also appear to have given rise to simple protein-tagging systems such as Sampylation in archaea and Urmylation in eukaryotes. However, other prokaryotic systems with Ubls of the YukD and other families, including one very close to Ub itself, developed additional elements that more closely resemble the eukaryotic state in possessing an E2, a RING-type E3, or both of these components. Additionally, prokaryotes have evolved conjugation systems that are independent of Ub ligases, such as the Pup system.

As usual, we are dealing here with distant similarities, but there is no doubt that the ubiquitin system as we know it appears in eukaryotes.

But what about its evolutionary history in eukaryotes?

We have already mentioned the extremely high conservation of ubiquitin itself.

UBA1, the main E1 enzyme, is rather well conserved from fungi to humans: 60% identity, 1282 bits, 1.21 bits per aminoacid (baa).

E2s are small enzymes, extremely conserved from fungi to humans: 86% identity, for example, for UB2D2, a 147 AAs molecule.

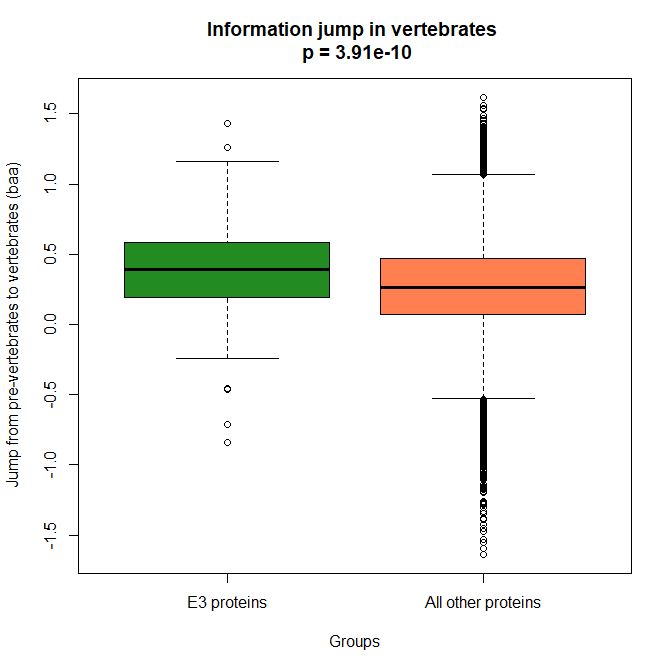

E3s, of course, are the most interesting issue. This big family of proteins behaves in different ways, consistently with its highly specific functions.

It is difficult to build a complete list of E3 proteins. I have downloaded from Uniprot a list of reviewed human proteins including “E3 ubiquitun ligase” in their name: a total of 223 proteins.

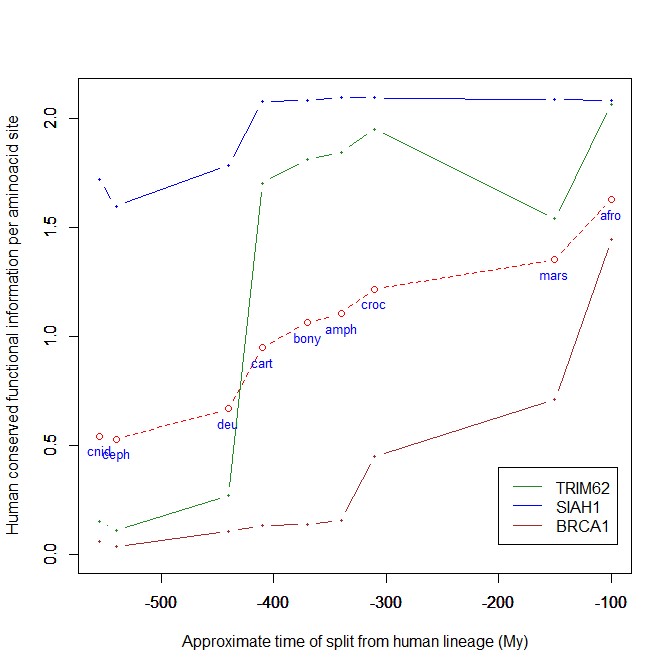

The mean evolutionary behavior of this group in metazoa is rather different from protein to protein. However, as a group these proteins exhibit an information jump in vertebrates which is significantly higher than the jump in all other proteins:

As we already know, this is evidence that this class of proteins is highly engineered in the transition to vertebrates. That is consistent with the need to finely regulate many cellular processes, most of which are certainly highly specific for different groups of organisms.

The highest vertebrate jump, in terms of bits per aminoacid, is shown in my group by the E3 ligase TRIM62. also known as DEAR1 (Q9BVG3), a 475 AAs long protein almost absent in pre-vertebrates (best hit 129 bits, 0.27 baa in Branchiostoma belcheri) and which flaunts an amazing jump of 1.433684 baa in cartilaginous fish (810 bits, 1.705263 baa).

But what is this protein? It is a master regulator tumor suppressor gene, implied in immunity, inflammation, tumor genesis.

See here:

and here:

This is just to show what a single E3 ligase can be involved in!

An opposite example, from the point of view of evolutionary history, is SIAH1, an E3 ligase implied in proteosomal degradation of proteins. It is a 282 AAs long protein, which already exhibits 1.787234 baa (504 bits) of homology in deuterostomes, indeed already 1.719858 baa in cnidaria. However, in fungi the best hit is only 50.8 bits (0.18 baa). So, this is a protein whose engineering takes place at the start of metazoa, and which exhibits only a minor further jump in vertebrates (0.29 baa), which brings the protein practically to its human form already in cartilaginous fish (280 identities out of 282, 99%). Practically a record.

So, we can see that E3 ligases are a good example of a class of proteins which perform different specific functions, and therefore exhibit different evolutionary histories: some, like TRIM62, are vertebrate quasi-novelties, others, like SIAH1, are metazoan quasi-novelties. And, of course, there are other behaviours, like for example BRCA1, Breast cancer type 1 susceptibility protein, a protein 1863 AAs long which only in mammals acquires part of its final sequence configuration in humans.

The following figure shows the evolutionary history of the three proteins mentioned above.

An interesting example: NF-kB signaling

I will discuss briefly an example of how the Ubiquitin system interacts with some specific and complex final effector system. One of the best models for that is the NF-kB signaling.

NK-kB is a transcription factor family that is the final effector of a complex signaling pathway. I will rely mainly on the following recent free paper:

The Ubiquitination of NF-κB Subunits in the Control of Transcription

Here is the abstract:

Nuclear factor (NF)-κB has evolved as a latent, inducible family of transcription factors fundamental in the control of the inflammatory response. The transcription of hundreds of genes involved in inflammation and immune homeostasis require NF-κB, necessitating the need for its strict control. The inducible ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of the cytoplasmic inhibitor of κB (IκB) proteins promotes the nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity of NF-κB. More recently, an additional role for ubiquitination in the regulation of NF-κB activity has been identified. In this case, the ubiquitination and degradation of the NF-κB subunits themselves plays a critical role in the termination of NF-κB activity and the associated transcriptional response. While there is still much to discover, a number of NF-κB ubiquitin ligases and deubiquitinases have now been identified which coordinate to regulate the NF-κB transcriptional response. This review will focus the regulation of NF-κB subunits by ubiquitination, the key regulatory components and their impact on NF-κB directed transcription.

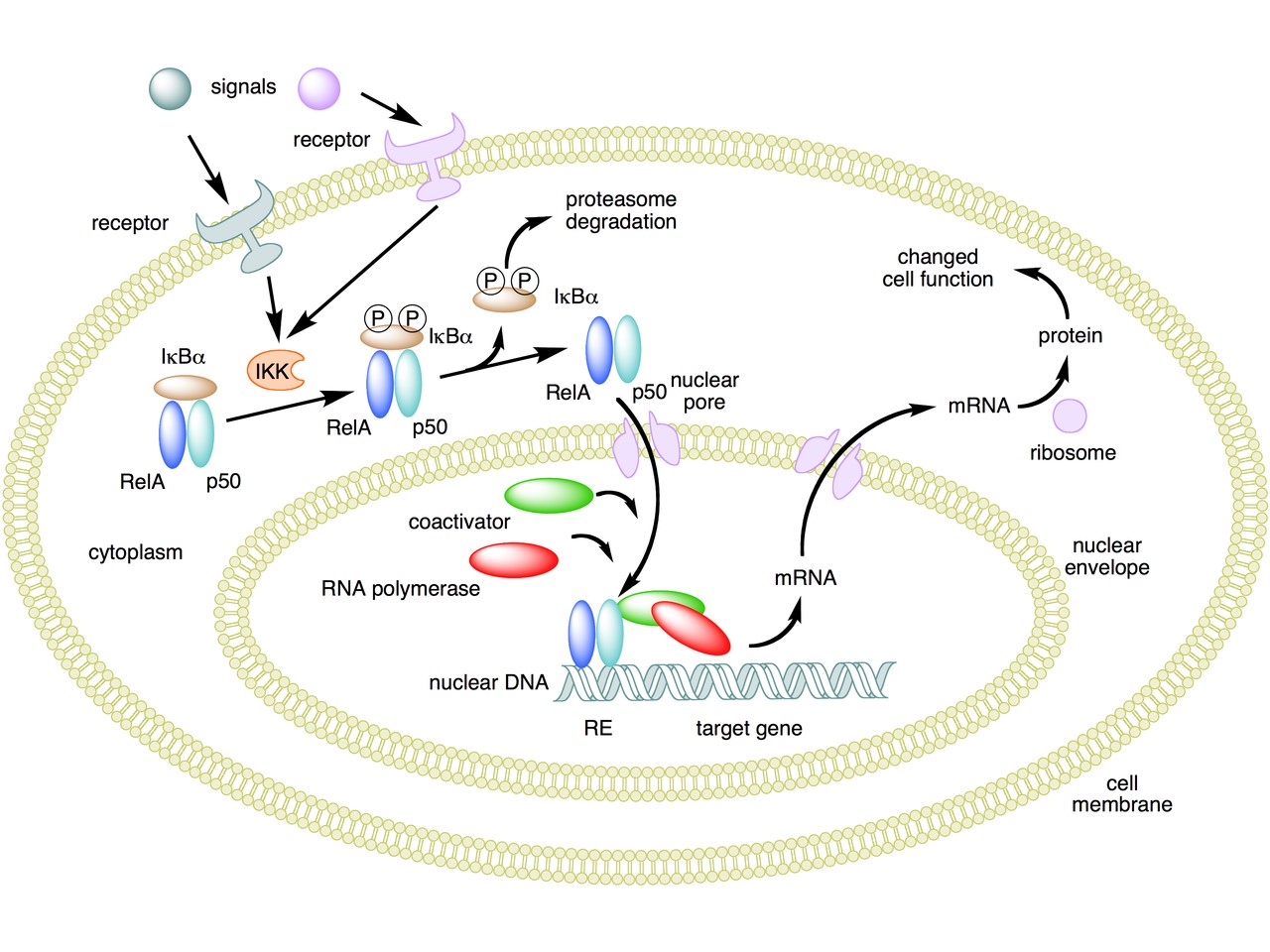

The following figure sums up the main features of the canonical activation pathway:

Here the NF-κB TF is essentially the heterodimer RelA – p50. Before activation, the NF-κB (RelA – p50) dimer is kept in an inactive state and remains in the cytoplasm because it is linked to the IkB alpha protein, an inhibitor of its function.

Activation is mediated by a signal-receptor interaction, which starts the whole pathway. A lot of different signals can do that, adding to the complexity, but we will not discuss this part here.

As a consequence of receptor activation, another protein complex, IκB kinase (IKK), accomplishes the Phosphorylation of IκBα at serines 32 and 36. This is the signal for the ubiquitination of the IkB alpha inhibitor.

This ubiqutination targets IkB alpha for proteosomal degradation. But how is it achieved?

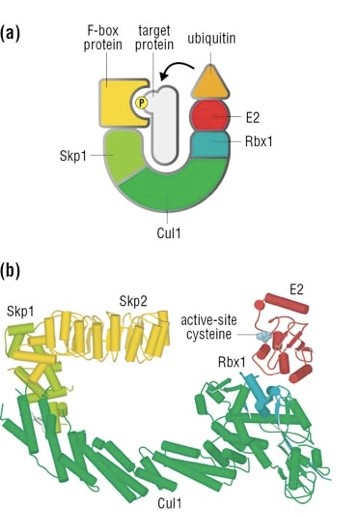

Well, things are not so simple. A whole protein complex is necessary, a complex which implements many different ubiquitinations in different contexts, including this one.

The complex is made by 3 basic proteins:

- Cul1 (a scaffold protein, 776 AAs)

- SKP1 (an adaptor protein, 163 AAs)

- Rbx1 (a RING finger protein with E3 ligase activity, 108 AAs)

Plus:

- An F-box protein (FBP) which changes in the different context, and confers specificity.

In our context, the F box protein is called beta TRC (605 AAs).

Once the IkB alpha inhibitor is ubiquinated and degraded in the proteasome, the NF-κB dimer is free to translocate to the nucleus, and implement its function as a transcription factor (which is another complex issue, that we will not discuss).

OK, this is only the canonical activation of the pathway.

In the non canonical pathway (not shown in the figure) a different set of signals, receptors and activators acts on a different NF-κB dimer (RelB – p100). This dimer is not linked to any inhibitor, but is itself inactive in the cytoplasm. As a result of the signal, p100 is phosphorylated at serines 866 and 870. Again, this is the signal for ubiquitination.

This ubiquitination is performed by the same complex described above, but the result is different. P100 is only partially degraded in the proteasome, and is transformed into a smaller protein, p52, which remains linked to RelB. The RelB – p52 dimer is now an active NF-κB Transcription Factor, and it can relocate to the nucleus and act there.

But that’s not all.

- You may remember that RelA (also called p 65) is one of the two components of NF-kB TF in the canonical pathway (the other being p 50). Well, RelA is heavily controlled by ubiquitination after it binds DNA in the nucleus to implement its TF activity. Ubiquitination (a very complex form of it) helps detachment of the TF from DNA, and its controlled degradation, avoiding sustained expression of NF-κB-dependent genes. For more details, see section 4 in the above quoted paper: “Ubiquitination of NF-κB”.

- The activation of IKK in both the canonical and non canonical pathway after signal – receptor interaction is not so simple as depicted in Fig. 6. For more details, look at Fig. 1 in this paper: Ubiquitin Signaling in the NF-κB Pathway. You can see that, in the canonical pathway, the activation of IKK is mediated by many proteins, including TRAF2, TRAF6, TAK1, NEMO.

- TRAF2 is a key regulator on many signaling pathways, including NF-kB. It is an E3 ubiquitin ligase. From Uniprot: “Has E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase activity and promotes ‘Lys-63’-linked ubiquitination of target proteins, such as BIRC3, RIPK1 and TICAM1. Is an essential constituent of several E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase complexes, where it promotes the ubiquitination of target proteins by bringing them into contact with other E3 ubiquitin ligases.”

- The same is true of TRAF6.

- NEMO (NF-kappa-B essential modulator ) is also a key regulator. It is not an ubiquinating enzyme, but it is rather heavily regulated by ubiquitination. From Uniprot: “Regulatory subunit of the IKK core complex which phosphorylates inhibitors of NF-kappa-B thus leading to the dissociation of the inhibitor/NF-kappa-B complex and ultimately the degradation of the inhibitor. Its binding to scaffolding polyubiquitin seems to play a role in IKK activation by multiple signaling receptor pathways. However, the specific type of polyubiquitin recognized upon cell stimulation (either ‘Lys-63’-linked or linear polyubiquitin) and its functional importance is reported conflictingly.”

- In the non canonical pathway, the activation of IKK alpha after signal – receptor interaction is mediated by other proteins, in particular one protein called NIK (see again Fig. 1 quoted above). Well, NIK is regulated by two different types of E3 ligases, with two different types of polyubiquitination:

- cIAP E3 ligase inactivates it by constant degradation using a K48 chain

- ZFP91 E3 ligase stabilizes it using a K63 chain

See here:

Non-canonical NF-κB signaling pathway.

In particular, Fig. 3

These are only some of the ways the ubiquitin system interacts with the very complex NF-kB signaling system. I hope that’s enough to show how two completely different and complex biological systems manage to cooperate by intricate multiple connections, and how the ubiquitin system can intervene at all levels of another process. What is true for the NF-kB signaling pathway is equally true for a lot of other biological systems, indeed for almost all basic cellular processes.

But this OP is already too long, and I have to stop here.

As usual, I want to close with a brief summary of the main points:

- The Ubiquitin system is a very important regulation network that shows two different signatures of design: amazing complexity and an articulated semiotic structure.

- The complexity is obvious at all levels of the network, but is especially amazing at the level of the hundreds of E3 ligases, that can recognize thousands of different substrates in different contexts.

- The semiosis is obvious in the Ubiquitin Code, a symbolic code of different ubiquitin configurations which serve as specific “tags” that point to different outcomes.

- The code is universally implemented and shared in eukaryotes, and allows control on almost all most important cellular processes.

- The code is written by the hundreds of E3 ligases. It is read by the many interactors with ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs).

- The final outcome is of different types, including degradation, endocytosis, protein signaling, and so on.

- The interaction of the Ubiquitin System with other complex cellular pathways, like signaling pathways, is extremely complex and various, and happens at many different levels and by many different interacting proteins for each single pathway.

PS:

Thanks to DATCG for pointing to this video in three parts by Dr. Raymond Deshaies, was Professor of Biology at the California Institute of Technology and an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. On iBiology Youtube page:

A primer on the ubiquitin-proteasome system

Cullin-RING ubiquitin ligases: structure, structure, mechanism, and regulation

Targeting the ubiquitin-proteasome system in cancer