It’s time to start delivering on a promise to address “warrant, knowledge, logic and first duties of reason as a cluster,” even at risk of being thought pedantic. Our civilisation is going through a crisis of confidence, down to the roots. If it is to be restored, that is where we have to start, and in the face of rampant hyperskepticism, relativism, subjectivism, emotivism, outright nihilism and irrationality, we need to have confidence regarding knowledge.

Doing my penance, I suppose: these are key issues and so here I stand, in good conscience, I can do no other, God help me.

For a start, from the days of Plato, knowledge has classically been defined as “justified, true belief.” However, in 1963, the late Mr Gettier put the cat in among the pigeons, with Gettier counter-examples; which have since been multiplied. In effect, there are circumstances (and yes, sometimes seemingly contrived, but these are instructive thought exercises) in which someone or a circle may be justified to hold a belief but on taking a wider view such cannot reasonably be held to be a case of knowledge.

As a typical thought exercise, consider a circle of soldiers and sailors on some remote Pacific island, who are eagerly awaiting a tape of a championship match sent out by the usual morale units. They get it, play it and rejoice that team A has won over team B (and the few who thought otherwise have to cough up on their bets to the contrary). Unbeknownst to them, through clerical error, it was last year’s match, which had the same A vs B match-up and more or less the same outcome. They are justified — have a right — to believe, what they believe is so, but somehow the two fail to connect leading to accidental, not reliable arrival at truth.

Knowledge must be built of sterner stuff.

Ever since, epistemology as a discipline, has struggled to rebuild a solid consensus on what knowledge is.

Plantinga weighed in with a multi-volume study, championing warrant, which(as we just noted) is at first defined by bill of requisites. That is, we start with what it must do. So, warrant — this builds on the dictionary/legal/commercial sense of a reliable guarantee of performance “as advertised” — will be whatever reliably converts beliefs we have a right to into knowledge.

The challenge being, to fill in the blank, “Warrant is: __________ .”

Plantinga then summarises, in his third volume:

The question is as old as Plato’s Theaetetus: what is it that distinguishes knowledge from mere true belief? What further quality or quantity must a true belief have, if it is to constitute knowledge? This is one of the main questions of epistemology. (No doubt that is why it is called ‘theory of knowledge’.) Along with nearly all subsequent thinkers, Plato takes it for granted that knowledge is at least true belief: you know a proposition p only if you believe it, and only if it is true. [–> I would soften to credibly, true as we often use knowledge in that softer, defeat-able sense cf Science] But Plato goes on to point out that true belief, while necessary for knowledge, is clearly not sufficient: it is entirely possible to believe something that is true without knowing it . . .

[Skipping over internalism vs externalism, Gettier, blue vs grue or bleen etc etc] Suppose we use the term ‘warrant’ to denote that further quality or quantity (perhaps it comes in degrees), whatever precisely it may be, enough of which distinguishes knowledge from mere true belief. Then our question (the subject of W[arrant and] P[roper] F[unction]): what is warrant?

My suggestion (WPF, chapters 1 and 2) begins with the idea that a belief has warrant only if it is produced by cognitive faculties that are functioning properly, subject to no disorder or dysfunction—construed as including absence of impedance as well as pathology. The notion of proper function is fundamental to our central ways of thinking about knowledge. But that notion is inextricably bound with another: that of a design plan.37

Human beings and their organs are so constructed that there is a way they should work, a way they are supposed to work, a way they work when they work right; this is the way they work when there is no malfunction . . . We needn’t initially take the notions of design plan and way in which a thing is supposed to work to entail conscious design or purpose [–> design, often is naturally evident, e.g. eyes are to see and ears to hear, both, reasonably accurately] . . .

Accordingly, the first element in our conception of warrant (so I say) is that a belief has warrant for someone only if her faculties are functioning properly, are subject to no dysfunction, in producing that belief.39 But that’s not enough.

Many systems of your body, obviously, are designed to work in a certain kind of environment . . . . this is still not enough. It is clearly possible that a belief be produced by cognitive faculties that are functioning properly in an environment for which they were designed, but nonetheless lack warrant; the above two conditions are not sufficient. We think that the purpose or function of our belief-producing faculties is to furnish us with true (or verisimilitudinous) belief. As we saw above in connection with the F&M complaint [= Freud and Marx], however, it is clearly possible that the purpose or function of some belief-producing faculties or mechanisms is the production of beliefs with some other virtue—perhaps that of enabling us to get along in this cold, cruel, threatening world, or of enabling us to survive a dangerous situation or a life-threatening disease.

So we must add that the belief in question is produced by cognitive faculties such that the purpose of those faculties is that of producing true belief.

More exactly, we must add that the portion of the design plan governing the production of the belief in question is aimed at the production of true belief (rather than survival, or psychological comfort, or the possibility of loyalty, or something else) . . . .

[W]hat must be added is that the design plan in question is a good one, one that is successfully aimed at truth, one such that there is a high (objective) probability that a belief produced according to that plan will be true (or nearly true). Put in a nutshell, then, a belief has warrant for a person S only if that belief is produced in S by cognitive faculties functioning properly (subject to no dysfunction) in a cognitive environment [both macro and micro . . . ] that is appropriate for S’s kind of cognitive faculties, according to a design plan that is successfully aimed at truth. We must add, furthermore, that when a belief meets these conditions and does enjoy warrant, the degree of warrant it enjoys depends on the strength of the belief, the firmness with which S holds it. This is intended as an account of the central core of our concept of warrant; there is a penumbral area surrounding the central core where there are many analogical extensions of that central core; and beyond the penumbral area, still another belt of vagueness and imprecision, a host of possible cases and circumstances where there is really no answer to the question whether a given case is or isn’t a case of warrant.41 [Warranted Christian Belief (NY/Oxford: OUP, 2000), pp 153 ff. See onward, Warrant, the Current Debate and Warrant and Proper Function; also, by Plantinga.]

So, we may profitably distinguish [a] Plantinga’s specification (bill of requisites) for warrant and [b] his theory of warrant. The latter, being (for the hard core):

a belief has warrant for a person S only if that belief is produced in S by cognitive faculties functioning properly (subject to no dysfunction) in a cognitive environment [both macro and micro . . . ] that is appropriate for S’s kind of cognitive faculties, according to a design plan that is successfully aimed at truth.

Obviously, warrant comes in degrees, which is just what we need to have. Certain things are known to utterly unchangeable certainty, others are to moral certainty, others for good reason are held to be reasonably reliable though not certain enough to trust when the stakes are high, other things are in doubt as to whether they are knowledge, some things outright fail any responsible test.

That’s why I have taken up and commend a modified form, recognising that what we think is credibly, reliably true today may oftentimes be corrected for cause tomorrow. (Back in High School Chemistry class, I used to imagine a courier arriving at the door to deliver the latest updates to our teacher.)

Yes, I accept that many knowledge claims are defeat-able, so open-ended and provisional.

Indeed, that is part of what distinguishes the prudence and fair-mindedness of sober knowledge claims hard won and held or even stoutly defended in the face of uncertainty and challenge from the false certitude of blind ideologies. Especially, where deductive logical schemes can have no stronger warrant than their underlying axioms and assumptions and where inductive warrant provides support, not utterly certain, incorrigible, absolute demonstration.

That said, we must recognise that some few things are self-evident, e.g.:

While self-evident truths cannot amount to enough to build a worldview, they can provide plumb line tests relevant to the reliability of warrant for what we accept as knowledge:

Such, of course, bring to the fore Ciceronian first duties of reason:

Marcus [in de Legibus, introductory remarks, C1 BC, being Cicero himself]: . . . we shall have to explain the true nature of moral justice, which is congenial and correspondent with the true nature of man [–> we are seeing the root vision of natural law, coeval with our humanity] . . . . “Law (say [“many learned men”]) is the highest reason, implanted in nature, which prescribes those things which ought to be done, and forbids the contrary” . . . . They therefore conceive that the voice of conscience is a law, that moral prudence is a law [–> a key remark] , whose operation is to urge us to good actions, and restrain us from evil ones . . . . the origin of justice is to be sought in the divine law of eternal and immutable morality. This indeed is the true energy of nature, the very soul and essence of wisdom, the test of virtue and vice.

We may readily expand such first duties of reason: to truth, to right reason, to prudence, to sound conscience, to neighbour, so also to fairness and justice. Where, it may readily be seen that the would-be objector invariably appeals to the said duties. Does s/he object, false, or doubtfully so, or errors of reason, or failure to warrant, or unfairness or the like, alike, s/he appeals to the very same duties, collapsing in self-referentiality. So, instead, let us acknowledge that these are inescapable, true, self-evident.

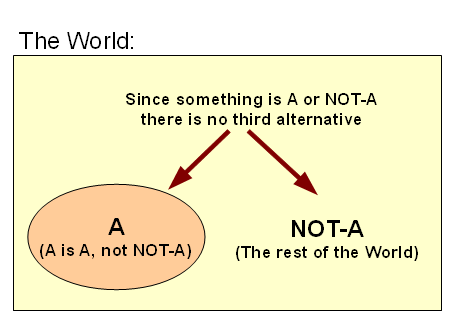

It may help, too to bring out first principles of right reason, such as:

Expanding as a first list:

Such enable us to better use our senses and faculties to build knowledge. END

U/D May 16, regarding the Overton window, first, just an outline:

Next, as applied:

Backgrounder, on the political spectrum: