The latest flare-ups in the debates over design theory in and around UD have pivoted on the Law of non-contradiction; one of the most debated classical principles of logic.

Why on earth is that so?

The simple short answer is: if we are to make progress in debates and discussions, we must be at minimum agreed on being reasonable and rational.

In more details, LNC is one of a cluster of first principles of right reason that are pivotal to core rationality, and for years now, debates over design theory issues have often tracked back to a peculiar characteristic of the evolutionary materialist worldview: it tends strongly to reject the key laws of thought, especially, identity, excluded middle and non-contradiction, with the principle of sufficient reason (the root of the principle of causality) coming up close behind.

What is sadly ironic about all of this, is that hose who would overthrow such first principles of right reason do not see that they are sawing off the branch on which we must all sit, if we are to be rational.

Why do I say this?

Let me first excerpt a discussion on building worldviews, as I recently appended to a discussion on quantum mechanics used to try to dismiss the law of non-contradiction:

____________

>>. . . though it is quite unfashionable to seriously say such nowadays (an indictment of our times . . .), to try to deny the classic three basic principles of right reason — the law of identity, that of non-contradiction, and that of the excluded middle — inevitably ends up in absurdity.

For, to think at all, we must be able to distinguish things (or else all would be confusion and chaos), and these laws immediately follow from that first act of thought.

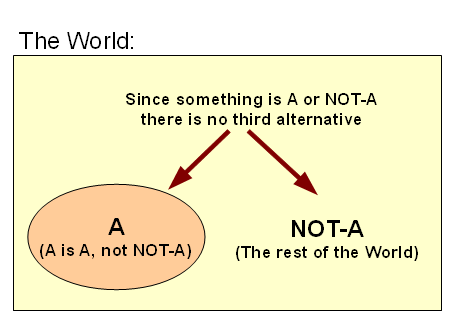

A diagram showing the world split into two distinct labelled parts, A and NOT-A, will help us see how naturally this happens:

If at a given moment we distinctly identify and label some thing, A — say, a bright red ball on a table — we mark a mental border-line and also necessarily identify NOT-A as “the rest of the World.” We thus have a definite separation of the World into two parts, and it immediately and undeniably holds that:

(a) the part labelled A will be A (symbolically, [A => A] = 1),

(b) A will not be the same as NOT-A ( [A AND NOT-A] = 0); and

(c) there is no third option to being A or NOT-A ( [A OR NOT-A] = 1).

So, we see how naturally the laws of (a) identity, (b) non-contradiction (or, non-confusion!), and (c) the excluded middle swing into action. This naturalness also extends to the world of statements that assert that something is true or false, as we may see from Aristotle’s classic remark in his Metaphysics 1011b (loading the 1933 English translation):

. . . if it is impossible at the same time to affirm and deny a thing truly, it is also impossible for contraries to apply to a thing at the same time; either both must apply in a modified sense, or one in a modified sense and the other absolutely.

Nor indeed can there be any intermediate between contrary statements, but of one thing we must either assert or deny one thing, whatever it may be. This will be plain if we first define truth and falsehood. To say that what is is not, or that what is not is, is false; but to say that what is is, and what is not is not, is true; and therefore also he who says that a thing is or is not will say either what is true or what is false. [Emphases added]

So, we can state the laws in more or less traditional terms:

[a] A thing, A, is what it is (the law of identity);

[b] A thing, A, cannot at once be and not-be (the law of non-contradiction);

[c] A thing, A, is or it is not, but not both or neither (the law of the excluded middle).

Public domain

Public domainFor a fire to begin or to continue, we need (1) fuel, (2) heat, (3) an oxidiser [usually oxygen] and (4) an un- interfered- with heat-generating chain reaction mechanism. (For, Halon fire extinguishers work by breaking up the chain reaction.) Each of the four factors is necessary for, and the set of four are jointly sufficient to begin and sustain a fire. We thus see four contributory factors, each of which is necessary [knock it out and you block or kill the fire], and together they are sufficient for the fire.

We thus see the principle of cause and effect. That is,

[d] if something has a beginning or may cease from being — i.e. it is contingent — it has a cause.

Common-sense rationality, decision-making and science alike are founded on this principle of right reason: if an event happens, why — and, how? If something begins or ceases to exist, why and how? If something is sustained in existence, what factors contribute to, promote or constrain that effect or process, how? The answers to these questions are causes.

Without the reality behind the concept of cause the very idea of laws of nature would make no sense: events would happen anywhere, anytime, with no intelligible reason or constraint.

As a direct result, neither rationality nor responsibility would be possible; all would be a confused, unintelligible, unpredictable, uncontrollable chaos. Also, since it often comes up, yes: a necessary causal factor is a causal factor — if there is no fuel, the car cannot go because there is no energy source for the engine. Similarly, without an unstable nucleus or particle, there can be no radioactive decay and without a photon of sufficient energy, there can be no photo-electric emission of electrons: that is, contrary to a common error, quantum mechanical events or effects, strictly speaking, are not cause-less.

(By the way, the concept of a miracle — something out of the ordinary that is a sign that points to a cause beyond the natural order — in fact depends on there being such a general order in the world. In an unintelligible chaos, there can be no extra-ordinary signposts, as nothing will be ordinary or regular!)

However, there is a subtle facet to this, one that brings out the other side of the principle of sufficient reason. Namely, that there is a possible class of being that does not have a beginning, and cannot go out of existence; such are self-sufficient, have no external necessary causal factors, and as such cannot be blocked from existing. And it is commonly held that once there is a serious candidate to be such a necessary being, if the candidate is not contradictory in itself [i.e. if it is not impossible], it will be actual.

Or, we could arrive at effectively the same point another way, one which brings out what it means to be a serious candidate to be a necessary being:

If a thing does not exist it is either that it could, but just doesn’t happen to exist, or that it cannot exist because it is a conceptual contradiction, such as square circles, or round triangles and so on. Therefore, if it does exist, it is either that it exists contingently or that it is not contingent but exists necessarily (that is it could not fail to exist without contradiction). [–> The truth reported in “2 + 3 = 5” is a simple case in point; it could not fail without self-contradiction.] These are the four most basic modes of being and cannot be denied . . . the four modes are the basic logical deductions about the nature of existence.

That is, since there is no external necessary causal factor, such a being — if it is so — will exist without a beginning, and cannot cease from existing as one cannot “switch off” a sustaining external factor. Another possibility of course is that such a being is impossible: it cannot be so as there is the sort of contradiction involved in being a proposed square circle. So, we have candidates to be necessary beings that may not be possible on pain of contradiction, or else that may not be impossible, equally on pain of contradiction.

In addition, since matter as we know it is contingent, such a being will not be material. The likely candidates are: abstract, necessarily true propositions and an eternal mind, often brought together by suggesting that such truths are held in such a mind.

Strange thoughts, perhaps, but not absurd ones.

So also, if we live in a cosmos that (as the cosmologists tell us) seems — on the cumulative balance of evidence — to have had a beginning, then it too is credibly caused. The sheer undeniable actuality of our cosmos then points to the principle that from a genuine nothing — not matter, not energy, not space, not time, not mind etc. — nothing will come. So then, if we can see things that credibly have had a beginning or may come to an end; in a cosmos of like character, we reasonably and even confidently infer that a necessary being is the ultimate, root-cause of our world; even through suggestions such as a multiverse (which would simply multiply the contingent beings) . . . >>

____________

[Added, Feb 21:] Let us boil this down to a summary list of six first principles of right reason in a form we could write out on the back of the proverbial envelope, with a little help from SB:

{{Consider the world:

|| . . . ||

Identify some definite A in it:

|| . . . (A) . . . NOT-A (the rest of the world) . . . ||

Now, let us analyse:

[1] A thing, A, is what it is (the law of identity);

[2] A thing, A, cannot at once be and not-be (the law of non-contradiction). It is worth clipping Wiki’s cites against known interest from Aristotle in Metaphysics, as SB has done above:

1. ontological*: “It is impossible that the same thing belong and not belong to the same thing at the same time and in the same respect.” (1005b19-20)

[*NB: Ontology, per Am HD etc, is “The branch of metaphysics that deals with the nature of being,” and the ontological form of the claim is talking about that which really exists or may really exist. Truth is the bridge between the world of thoughts and perceptions and that of external reality: truth says that what is is, and what is not is not.]

2. psychological: “No one can believe that the same thing can (at the same time) be and not be.” (1005b23-24)

3. logical: “The most certain of all basic principles is that contradictory propositions are not true simultaneously.” (1011b13-14)

[3] A thing, A, is or it is not, but not both or neither (the law of the excluded middle).

[4] “to say that what is is, and what is not is not, is true.” (Aristotle, on what truth is)

[5] “Of everything that is, it can be found why it is.” (Principle of sufficient Reason, per Schopenhauer.)

[6] If something has a beginning or may cease from being — i.e. it is contingent — it has a cause.* (Principle of causality, a direct derivative of 5)

_________*F/N: Principles 5 & 6 point to the possibility of necessary, non contingent beings, e.g. the truth in 2 + 3 = 5 did not have a beginning, cannot come to an end, and is not the product of a cause, it is an eternal reality. The most significant candidate necessary being is an eternal Mind. Indeed, down this road lies a path to inferring and arguably warranting the existence of God as architect, designer and maker — thus, creator — of the cosmos. (Cf Plato’s early argument along such lines, here.)}}

It would seem that the matter is obvious at this point.

Indeed, as UD’s blog owner cited yesterday from Wikipedia, testifying against known predominant ideological interest:

The law of non-contradiction and the law of excluded middle are not separate laws per se, but correlates of the law of identity. That is to say, they are two interdependent and complementary principles that inhere naturally (implicitly) within the law of identity, as its essential nature. To understand how these supplementary laws relate to the law of identity, one must recognize the dichotomizing nature of the law of identity. By this I mean that whenever we ‘identify’ a thing as belonging to a certain class or instance of a class, we intellectually set that thing apart from all the other things in existence which are ‘not’ of that same class or instance of a class. In other words, the proposition, “A is A and A is not ~A” (law of identity) intellectually partitions a universe of discourse (the domain of all things) into exactly two subsets, A and ~A, and thus gives rise to a dichotomy. As with all dichotomies, A and ~A must then be ‘mutually exclusive’ and ‘jointly exhaustive’ with respect to that universe of discourse. In other words, ‘no one thing can simultaneously be a member of both A and ~A’ (law of non-contradiction), whilst ‘every single thing must be a member of either A or ~A’ (law of excluded middle).

The article (which seems to have been around since about 2004) goes on to say:

What’s more, since we cannot think without that we make use of some form of language (symbolic communication), for thinking entails the manipulation and amalgamation of simpler concepts in order to form more complex ones, and therefore, we must have a means of distinguishing these different concepts. It follows then that the first principle of language (law of identity) is also rightfully called the first principle of thought, and by extension, the first principle reason (rational thought).

Schopenhauer sums up aptly:

The laws of thought can be most intelligibly expressed thus:

- Everything that is, exists.

- Nothing can simultaneously be and not be.

- Each and every thing either is or is not.

- Of everything that is, it can be found why it is.

There would then have to be added only the fact that once for all in logic the question is about what is thought and hence about concepts and not about real things. [Manuscript Remains, Vol. 4, “Pandectae II,” §163. NB: Of course, the bridge from the world of thought to the world of experienced reality is that we do live in a real world that we can think truly about. Going further, there are things about that world that are self-evidently true, starting with Josiah Royce’s “Error exists.”]

And again:

Through a reflection, which I might call a self-examination of the faculty of reason, we know that these judgments are the expression of the conditions of all thought and therefore have these as their ground. Thus by making vain attempts to think in opposition to these laws, the faculty of reason recognizes them as the conditions of the possibility of all thought. We then find that it is just as impossible to think in opposition to them as it is to move our limbs in a direction contrary to their joints. If the subject could know itself, we should know those laws immediately, and not first through experiments on objects, that is, representations (mental images). [On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason, §33.]

Similarly, Lord Russell states:

1. Law of identity: “Whatever is, is.”

2. Law of noncontradiction: “Nothing can both be and not be.”

3. Law of excluded middle: “Everything must either be or not be.”

(The Problems of Philosophy, p. 72)

The matter should be clear enough, and simple enough.

Sadly, it is not. There are some who would now say, of course you can define a logical world in which this is an axiom and by definition be true but that has nothing to do with reality.

That is why I had to further respond this morning:

____________

>>Let us start with a basic point, as can be seen in the discussion here on in context: the first step in serious thinking about anything, is to make relevant distinctions, so for each such case we divide the world into A and not-A.

(Notice the example of a bright red ball on a table. Or, you can take: Me and not-Me, etc etc. It helps to start with the concrete and obvious so keep that nice red ball you got when you were say 6 months old in mind.)

Once there is a clear distinction, the relevant laws of thought follow directly, let’s illustrate:

World: || . . . ||

On identifying a distinct thing, (A), we distinguish:

|| (A) . . . NOT-A . . . ||

From this seemingly simple and commonsensical act of marking a distinction with a sharp border so to speak, the following follows, once A is indeed identifiably distinct at a given time and place under given circumstances:

(a) the part labelled A will be A (symbolically, [A => A] = 1),

(b) A will not be the same as NOT-A ( [A AND NOT-A] = 0); and

(c) there is no third option to being A or NOT-A ( [A OR NOT-A] = 1).

Or, in broader terms:

[a] A thing, A, is what it is (the law of identity);

[b] A thing, A, cannot at once be and not-be (the law of non-contradiction);

[c] A thing, A, is or it is not, but not both or neither (the law of the excluded middle).

And since there is a tendency to use classical quotes, let me cite one, from Paul of Tarsus, on the significance of all this, even for the very act of speech, the basis for reasoned, verbalised thought:

1 Cor 14:6 Now, brothers, if I come to you and speak in tongues, what good will I be to you, unless I bring you some revelation or knowledge or prophecy or word of instruction? 7 Even in the case of lifeless things that make sounds, such as the flute or harp, how will anyone know what tune is being played unless there is a distinction in the notes? 8 Again, if the trumpet does not sound a clear call, who will get ready for battle? 9 So it is with you. Unless you speak intelligible words with your tongue, how will anyone know what you are saying? You will just be speaking into the air. 10 Undoubtedly there are all sorts of languages in the world, yet none of them is without meaning. 11 If then I do not grasp the meaning of what someone is saying, I am a foreigner to the speaker, and he is a foreigner to me. 12 So it is with you. Since you are eager to have spiritual gifts, try to excel in gifts that build up the church . . .

In short, the very act of intelligible communication pivots on precisely the ability to mark relevant distinctions. Indeed, the ASCII code we use for text tells us one English language alphanumeric character encodes answers to seven yes/no questions, why it takes up seven bits. (The eighth is a check-sum, useful to say reasonably confident that this is accurately transmitted, but that is secondary.)

So, let us get it deep into our bones: so soon as we are communicating or calculating using symbols, textual or aural, we are relying on the oh so often spoken against laws of thought. This BTW, is why I have repeatedly pointed out how when theoretical physicists make the traditional scratches on the proverbial chalk board, these principles are deeply embedded in the whole process.

These are not arbitrary mathematical conventions that can be made into axioms as we please, they are foundational to the very act of communication involved in writing or speaking about such things.

Beyond that all the attempts to wander over this and that result of science in a desperate attempt to deny or dismiss actually rely on what they would dismiss. They refute themselves through self-referential incoherence.

For instance, just now, someone has trotted out virtual particles.

Is this a distinct concept? Can something be and not be a virtual particle under the same circumstances?

If so, the suggested concept is simply confused (try, a square circle or a triangle with six corners); back to the drawing-board.

(But of course there are effects that are traced to their action, so they seem to have reality as entities acting in our world below the Einstein energy-time threshold of uncertainty. The process that leads us to that conclusion is riddled with the need to mark distinctions, and to recognise that distinctions mark distinct things.)

And, BTW, we can extend to the next level. The number represented by the numeral, 2, is real, but it is not itself a physical entity; it just constrains physical entities such that something with twoness in it can be split exactly by the half into equal piles.

Similarly, the truth asserted in the symbolised statement: 2 + 3 = 5 constrains physical reality, but is not itself a material reality built up of atoms or the like. All the way on to 1 + e^pi*i = 0, etc; thence the “unreasonable: effectiveness of ever so much of mathematics in understanding how the physical world works. That is, we have a real, abstract world that can even specify mathematical laws that specify what happens and what will not happen. Even, reliably.

All of this pivots on the significance of marking distinctions.

So, those who seek so desperately to dismiss the first principles of right reason, saw off the branch on which they must sit.

It is a sad reflection on our times, that we so often find it hard to see this.

I know, I know: “But, that’s DIFFERENT!” (I am quoting someone caught up in a cultic system, in response to correcting a logical error.)

No. It is NOT actually different, but if we are enmeshed in systems that make us think errors are true, the truth will — to us — seem to be wrong.

Which is part of why en-darkening errors are ever so entangling.

It takes time and effort for a critical mass of corrections to reach breaking point and suddenly we see things another way. In that process, empirical cases are crucial.

But, there is another relevant saying: experience is a very good teacher, but his fees are very dear. Alas for fools, they will learn from no other.

Sadly, there are yet worse fools who will not even learn from experience, no matter how painful.

But then; it is ever so for those bewitched by clever, but unsound, schemes.

I hope that a light is beginning to dawn.>>

____________

Now, it will come as no surprise to see that I come down on the therapeutic side not the litmus test side of the issue of using the LNC as a test of rationality and fitness to discuss matters.

That is, I hold that this particular confusion is so commonplace that the key issue is to help those enmeshed, recognising that this is going to take time and effort. In that context, it is the specifically, persistently and willfully disruptive, disrespectful, deceitful and uncivil who should face disciplinary action for cause; in defence of a civil forum where important ideas can be discussed civilly. For contrasts on why that is necessary, cf YouTube and the penumbra of anti-ID sites.

Having said that, what is on the table now is rationality itself.

That is how bad things are with our civilisation at the hands of its own intellectual elites.

Do you see why I speak of a civilisation facing mortal danger and all but fatally confused in the face of such peril?

And of course the weapon of choice for the willful confus-ers is to get us to swallow an absurdity. That guarantees loss of ability to discern true from false, sound from unsound, right from wrong. Then, also, when we are told the truth, because we have been led to believe a lie, we will often resist the truth for it will seem to be obviously false.

No wonder, the prophet Isaiah thundered out, nigh on 2800 years ago:

Isa 5:20 Woe to those who call evil good

and good evil,

who put darkness for light

and light for darkness,

who put bitter for sweet

and sweet for bitter.

21 Woe to those who are wise in their own eyes

and clever in their own sight . . .

We would do well to heed these grim words of warning, before it is too late for our civilisation. END

F/N: For those puzzling over issues raised in the name of quantum theory or the like, I suggest you go here for a first examination.