Heidegger famously posed this question, giving it redoubled force as a first question on critical analysis of worldviews:

To philosophize is to ask “Why are there essents rather than nothing?” Really to ask this question signifies: a daring attempt to fathom this unfathomable question by disclosing what it summons us to ask, to push our questioning to the very end. Where such an attempt occurs there is philosophy. [ M. Heidegger, An Introduction to Metaphysics, Yale University Press, New Haven and London (1959), pp. 7-8.]

Let’s explore, first pausing to see Prof Dawkins (dean of the notoriously unphilosophical new atheists) making needlessly heavy weather of the matter:

Clearly, the pivot of the matter is — again — logic of being: No-thing is non-being, which contrasts with being and as non-being can have no causal powers, were there ever utter no-thing [i.e., no reality whatsoever] such would forever obtain. Therefore if a world is, SOMETHING has always existed. And yes, eternity knocks at our doorstep, welcome or not.

However, logic of being is one of the many gaps in our dumbed down education systems and is not exactly a popular talking heads topic. So, let us again summarise for those needing (or needing to at last heed) a 101 in a nutshell:

So, the debate on origins of the world and of ourselves in it must be shaped by this prior question.

Where, we need a world root — and yes, this OP is about world roots: why is there at least one actual world, instead of utter non-being? — causally adequate to account for a fine tuned cosmos with information rich C-chemistry aqueous medium cell based life. Further, one with many complex body plans, and with freely rational [not merely computational] morally governed creatures in it — us.

Where, obviously, a claimed beginningless causal-temporal succession of finite duration prior stages [“years” for convenience] has to account for — not, beg the question of — traversal of an implicitly transfinite span in finite steps; a supertask. For, at any finitely remote past stage k on such a claim, k-1, k-2 . . . were already traversed, i.e. once one is claimed to have already reached k from the beginningless prior set of stages, one is implying that the traverse has already happened. But how? And no, a Russell-like declaration that one sees no problem or a similar [equivalent?] declaration of alleged inexplicable brute fact are nowhere near good enough. Those simply beg the question of implicit prior transfinite traverse.

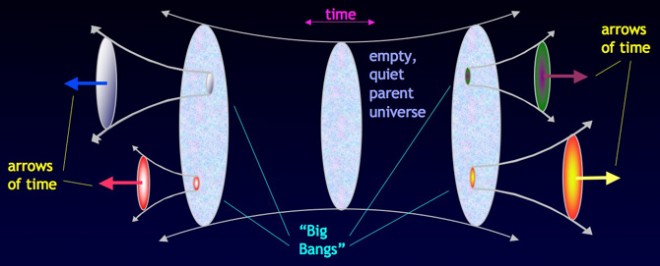

Where, no, if something is said to be the case, we have an epistemic right to ask why and how so. A mechanical and/pr stochastic explanatory candidate is one thing (here, facing the issue of heat death as concentrations of energy dissipate). A Fluctuation of the quantum foam view:

. . . faces the question, why is this not a Boltzmann brain world (a much more probable though vastly improbable fluctuation), and fails to account for the parent sub-universe, given the transfinite traverse challenge.

In passing, I note that the volitional action of a capable, choosing agent is a responsible explanation. One, we are quite familiar with from day to day.

So, again: why is there something, rather than nothing? END