In recent days, the issue of an infinite temporal past as a step by step causal succession has come up at UD. For, it seems the evolutionary materialist faces the unwelcome choice of a cosmos from a true nothing — non-being or else an actually completed infinite past succession of finite causal steps.

Durston:

>>To avoid the theological and philosophical implications of a beginning for the universe, some naturalists such as Sean Carroll suggest that all we need to do is build a successful mathematical model of the universe where time t runs from minus infinity to positive infinity. Although there is no problem in having t run from minus infinity to plus infinity with a mathematical model, the real past history of the universe cannot be a completed infinity of seconds that elapsed, one second at a time. There are at least two problems. First, an infinite real past requires a completed infinity, which is a single object and does not describe how history actually unfolds. Second, it is impossible to count down from negative infinity without encountering the problem of a potential infinity that never actually reaches infinity. For the real world, therefore, there must be a first event that occurred a finite amount of time ago in the past . . . [More] >>

Craig:

>Strictly speaking, I wouldn’t say, as you put it, that a “beginningless causal chain would be (or form) an actually infinite set.” Sets, if they exist, are abstract objects and so should not be identified with the series of events in time. Using what I would regard as the useful fiction of a set, I suppose we could say that the set of past events is an infinite set if the series of past events is beginningless. But I prefer simply to say that if the temporal series of events is beginningless, then the number of past events is infinite or that there has occurred an infinite number of past events . . . .

It might be said that at least there have been past events, and so they can be numbered. But by the same token there will be future events, so why can they not be numbered? Accordingly, one might be tempted to say that in an endless future there will be an actually infinite number of events, just as in a beginningless past there have been an actually infinite number of events. But in a sense that assertion is false; for there never will be an actually infinite number of events, since it is impossible to count to infinity. The only sense in which there will be an infinite number of events is that the series of events will go toward infinity as a limit.

But that is the concept of a potential infinite, not an actual infinite. Here the objectivity of temporal becoming makes itself felt. For as a result of the arrow of time, the series of events later than any arbitrarily selected past event is properly to be regarded as potentially infinite, that is to say, finite but indefinitely increasing toward infinity as a limit. The situation, significantly, is not symmetrical: as we have seen, the series of events earlier than any arbitrarily selected future event cannot properly be regarded as potentially infinite. So when we say that the number of past events is infinite, we mean that prior to today ℵ0 events have elapsed. But when we say that the number of future events is infinite, we do not mean that ℵ0 events will elapse, for that is false. [More]>>

Food for further thought. END

PS: As issues on numbers etc have become a major focus for discussion, HT DS here is a presentation of the overview:

Where also, this continuum result is useful:

PPS: As a blue vs pink punched paper tape example is used below, cf the real world machines

and the abstraction for mathematical operations:

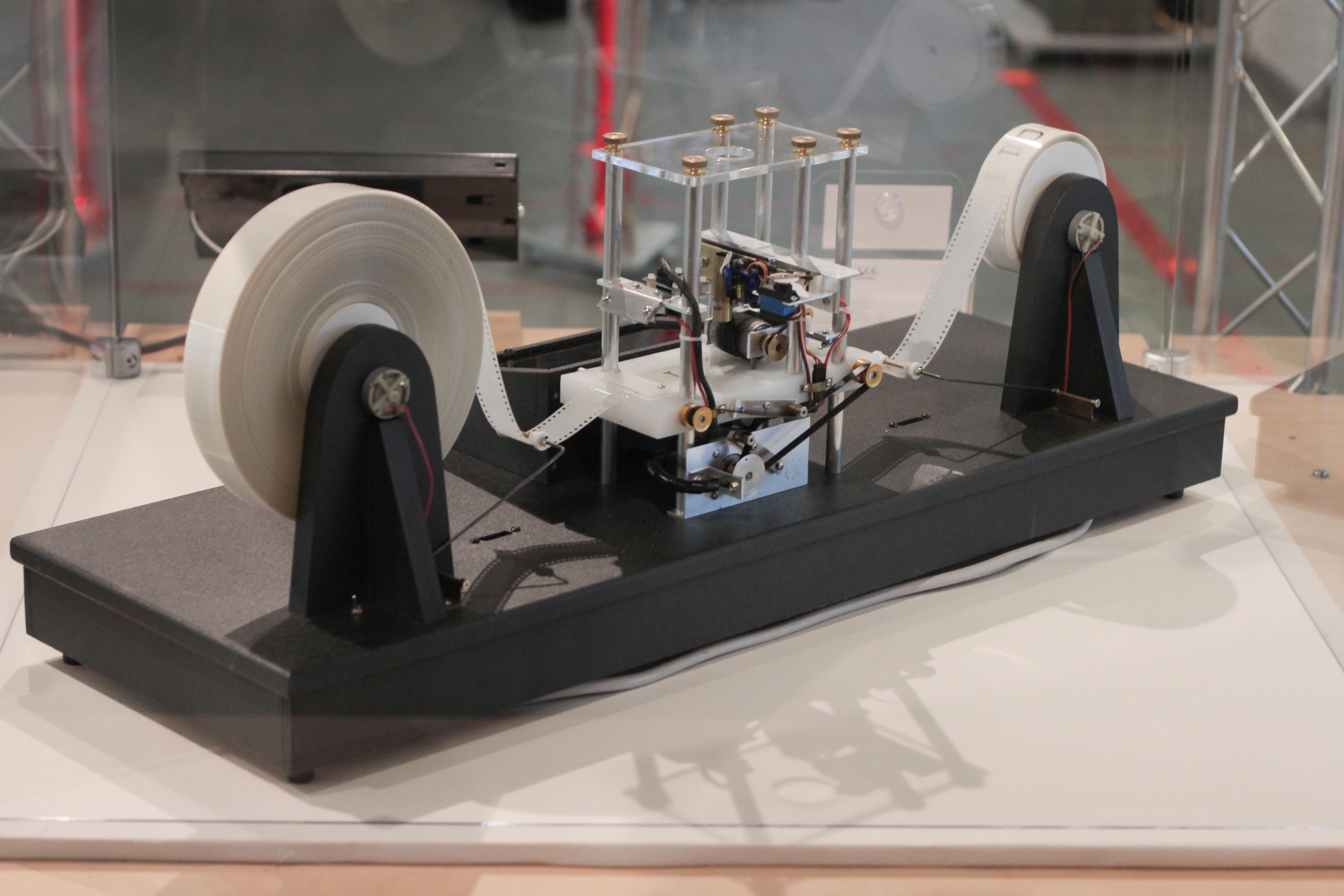

Note as well a Turing Machine physical model:

and its abstracted operational form for Mathematical analysis:

F/N: HT BA77, let us try to embed a video: XXXX nope, fails XXXX so instead let us instead link the vid page.