As this is my first OP, I thought it would be good to start with something really basic. And as I like explicit definitions in discussions, what could be better than discussing the definition of design in a place dedicated to the theory of Intelligent Design?

Maybe it is too basic to be interesting, but I believe that is not the case. Indeed, an explicit definition of design is rarely discussed, even here, and when it is discussed it seems to be very controversial, not only with our opponents, but even among those who are in the field of ID.

I have tried many times to give my personal definition of design, in the course of different discussions here. I am offering it again in this post, with some further detail, hoping to encourage the discussion on this important issue. All comments are welcome, and alternative definitions will be appreciated.

One point, IMO, cannot be denied: there is no sense in debating theories about Intelligent Design and its inference, if we have no clear idea of what we mean with the word design.

After giving my definition of design, I will give some brief definitions of what a design system, and a non design system are, with some examples of the application of those concepts to our biological issues about OOL and the evolution of life.

My definition

Let’s start with a few premises. “Design” is a process, well described by the verb “to design”, a transitive verb which implies a subject and an object. So, our definition will have to clearly identify:

a) What a designer is

b) What a designed object is

c) What the design process is

Moreover, what we are looking for here is a definition, not an interpretation or an explanation. IOWs, we must remain in the field of description of facts, and avoid as much as possible theories or specific worldviews. The only purpose of our definition is to be able to correctly use our words in our theories, not to imply our theories. In particular, in ID theory we need to be clear about what design is, because our theory is about recognizing and inferring design. Therefore, our definition must be an empirical description, and nothing else.

Now, to understand well the scenario of what “design” means in common language, let’s look at some very broad definitions from the Internet. Just to be original, let’s start with Wikipedia:

“Design is the creation of a plan or convention for the construction of an object or a system…

More formally design has been defined as follows.

(noun) a specification of an object, manifested by an agent, intended to accomplish goals, in a particular environment, using a set of primitive components, satisfying a set of requirements, subject to constraints;

(verb, transitive) to create a design, in an environment (where the designer operates)[2]

Another definition for design is a roadmap or a strategic approach for someone to achieve a unique expectation.”

Not bad, I would say!

Now, dictionary.com:

“de·sign

verb (used with object)

1. to prepare the preliminary sketch or the plans for (a work to be executed), especially to plan the formand structure of: to design a new bridge.

2. to plan and fashion artistically or skillfully.

3. to intend for a definite purpose: a scholarship designed for foreign students.

4. to form or conceive in the mind; contrive; plan: The prisoner designed an intricate escape.

5. to assign in thought or intention; purpose: He designed to be a doctor.”

(First five definitions. It goes on with others.)

And, finally, the Free Online Dictionary:

“de·sign

v. de·signed, de·sign·ing, de·signs

v.tr.

1.

a. To conceive or fashion in the mind; invent: design a good excuse for not attending the conference.

b. To formulate a plan for; devise: designed a marketing strategy for the new product.

2. To plan out in systematic, usually graphic form: design a building; design a computer program.

3. To create or contrive for a particular purpose or effect: a game designed to appeal to all ages.

4. To have as a goal or purpose; intend.

5. To create or execute in an artistic or highly skilled manner.

So, these are important premises, because it is highly desirable that our definition be truly compatible with the common meaning of the word.

At this point, I will give my explicit definition:

Design is a process where a conscious agent subjectively represents in his own consciousness some form and then purposefully outputs that form, more or less efficiently, to some material object.

We call the process “design”. We call the conscious agent who subjectively represents the initial form “designer”. We call the material object, after the process has taken place, “designed object”.

It looks simple, doesn’it? Well, it is simple. And I believe that it satisfies all our right expectations.

The above image of a girl in the act of drawing is a very good illustration of that. The girl is the designer, the paper with the drawing of a bird is the designed object. The photo has captured the empirical process of design.

Obviously, we are assuming here that the girl has subjectively represented the bird in her consciousness before designing it (is anyone objecting to that assumption?).

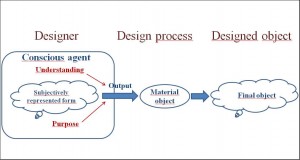

The following diagram sums up the main concepts in the definition.

Now, just a few clarifications, to anticipate inevitable objections:

1) I imply no special theory of what consciousness is, and no particular worldview. The only thing required is the recognition that conscious agents exist, and that they have conscious, subjective representations.

2) No explicit inference about causality is necessary here. Although it seems quite reasonable that the represented form is, at least in part, the cause of the form in the designed object, that assumption is not really necessary. The important point is that the final form must arise in the subjective representation first, and then in the designed object.

3) Nothing is stated in the definition about complexity. The designed form can be simple or complex, functional or not. The important point is that it is represented, and that the designer has the purpose of outputting it.

4) Nothing is stated here about intelligence. That is to simplify this post. The problem of intelligence can be dealt with separately.

5) Nothing is implied here about free will. While free will is a natural integration of a design theory, it is not necessary to assume its existence to define design.

Design systems

We can define a system “a design system” if, given an initial state A (which can be designed or not designed, indifferently), the evolution of the system in time, starting form A and up to another state A1, includes one or more design processes.

Conversely, we can define a system “a non design system” if, given an initial state A (which can be designed or not designed, indifferently), the evolution of the system in time, starting form A and up to another state A1, does not include any design process.

To exemplify, let’s take the problem of OOL. Here, the initial state A could be our planet at the beginning of its existence, and A1 our planet at a time when life in a specific form we know, for example prokaryotes, already exists. So, in this case the problem is simply: can the transition from A to A1 be satisfactorily explained as a non design system, or is it best explained as a design system?

If, on the other hand, our problem is the evolution of life after OOL, then our initial state A will be our planet with its prokaryotic life only, and our final state A1 can be our planet as it is today, with all the life forms we know. Again, the problem is: can the transition from A to A1 be satisfactorily explained as a non design system, or is it best explained as a design system? If we express the problem in this way, the existence of prokaryotic life is no more part of what we have to explain, because the problem we are considering for the moment is only the transition from A to A1, and in A that kind of life is already present.

Well, that’s all for the moment.