Cf follow up on laws of thought including cause, here

In our day, it is common to see the so-called Laws of Thought or First Principles of Right Reason challenged or dismissed. As a rule, design thinkers strongly tend to reject this common trend, including when it is claimed to be anchored in quantum theory.

Going beyond, here at UD it is common to see design thinkers saying that rejection of the laws of thought is tantamount to rejection of rationality, and is a key source of endless going in evasive rhetorical circles and refusal to come to grips with the most patent facts; often bogging down attempted discussions of ID issues.

The debate has hotted up over the past several days, and so it is back on the front burner.

But, why are design thinkers today inclined to swim so strongly against a cultural tide that may often seem to be overwhelming?

Perhaps, Wikipedia, speaking against known ideological inclination on the Law of Thought, may help us begin to see why:

That everything be ‘the same with itself and different from another’ (law of identity) is the self-evident first principle upon which all symbolic communication systems (languages) are founded, for it governs the use of those symbols (names, words, pictograms, etc.) which denote the various individual concepts within a language, so as to eliminate ambiguity in the conveyance of those concepts between the users of the language. Such a principle (law) is necessary because symbolic designators have no inherent meaning of their own, but derive their meaning from the language users themselves, who associate each symbol with an individual concept in a manner that has been conventionally prescribed within their linguistic group . . . .

we cannot think without making use of some form of language (symbolic communication), for thinking entails the manipulation and amalgamation of simpler concepts in order to form more complex ones, and therefore, we must have a means of distinguishing these different concepts. It follows then that the first principle of language (law of identity) is also rightfully called the first principle of thought, and by extension, the first principle reason (rational thought).

In short, to think reasonably about the world, we must mentally dichotomise, and once that is done, the first principles of right reason apply.

For instance (to connect to reality not just words), consider say a bright red ball on a table:

Where Jupiter (seen here in IR some days after the Shoemaker-Levy 9 multiple comet impact) is the ultimate “red ball” — but one — in our solar system:

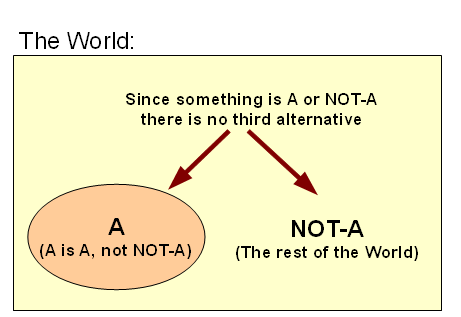

Or, analysing in terms of an abstraction of this observational/experiential situation that brings out the laws of thought and the issue of warrant against accuracy to experiential reality:

Okay, you may say: that addresses the world of thinking. In cases where we mark distinctions, then the distinction obtains, but that does not bridge to reality.

Or, does it?

So long as there is a distinction between the red ball on the table and the rest of the world, and so long as it is inevitable that we do know something about the world, on pain of absurdity, these will also apply to external reality. The laws are objective not just subjective.

Take, one who suggests there is an ugly gulch between our inner world of appearances and thoughts, and the outer one of things in themselves, so that we can never bridge the gap.

But, to make such a claim is to make a claim to know something about external reality, its alleged un-knowable nature.

Self-referential incoherence leading to confusion, in short.

(That will not faze some, but that only tells the rest of us, that such are beyond the reach of reason. Pray for them, that is their only hope.)

So, we are back at the objectivity of these first principles of right reason.

Let me now clip a comment just made in the KN thread:

This, from Wiki speaking against known ideological inclination, on the Laws of Thought c. Feb 2012 [cf Rationale], may help in understanding how the three key first principles of right reason are inextricably linked:

The law of non-contradiction and the law of excluded middle are not separate laws per se, but correlates of the law of identity. That is to say, they are two interdependent and complementary principles that inhere naturally (implicitly) within the law of identity, as its essential nature . . . whenever we ‘identify’ a thing as belonging to a certain class or instance of a class, we intellectually set that thing apart from all the other things in existence which are ‘not’ of that same class or instance of a class. In other words, the proposition, “A is A and A is not ~A” (law of identity) intellectually partitions a universe of discourse (the domain of all things) into exactly two subsets, A and ~A, and thus gives rise to a dichotomy. As with all dichotomies, A and ~A must then be ‘mutually exclusive’ and ‘jointly exhaustive’ with respect to that universe of discourse. In other words, ‘no one thing can simultaneously be a member of both A and ~A’ (law of non-contradiction), whilst ‘every single thing must be a member of either A or ~A’ (law of excluded middle).

See what happens so soon as we make a clear and crisp distinction?

Therefore, why I highlight how we are using glyphs, characters, words, sentences, symbols, relations, expressions etc in trying to make all of these novel “logics” or Quantum speculations, etc?

That is, we inescapably are marking distinctions and are dichotomising reality, into (T|NOT-T) . . . (H|NOT_H) . . . (A|NOT_A) . . . (T|NOT_T) etc. just to type out a sentence. The stability of identity of T, H, A, T then leads straight to the correlates, that we have marked a distinction that is “‘mutually exclusive’ and ‘jointly exhaustive’ with respect to that universe of discourse.”

The implication is, that so soon as we make sharp distinctions and identify things on the one side thereof, we are facing the underlying significance of such distinctions: A is A, A is not NOT_A, and there is not a fuzzy thing out there other than A and NOT_A. of course, there are spectra or trends or timelines that credibly have a smooth gradation along a continuum, there are superpositions and there are trichotomies etc [which can be reduced to structured sets of dichotomies). But so soon as we are even just talking of this, we are inescapably back to the business of making (A|NOT_A) distinctions.

That is where I find myself standing this morning.

What about you? END