As a follow-up to my previous post:

I am presenting here some results obtained by a general application, expanded to the whole human proteome, of the procedure already introduced in that post.

Main assumptions.

The aim of the procedure is to measure a well defined equivalent of functional information in proteins: the information that is conserved throughout long evolutionary times, in a well specified evolutionary line.

The simple assumption is that such information, which is not modified by neutral variation in a time span of hundreds of million years, is certainly highly functionally constrained, and is therefore a very good empirical approximation of the value of functional information in a protein.

In particular, I will use the proteins in the human proteome as “probes” to measure the information that is conserved from different evolutionary timepoints.

The assumption here is very simple. Let’s say that the line that includes humans (let’s call it A) splits from some different line (let’s call it B) at some evolutionary timepoint T. Then, the homology that we observe in a protein when we compare organisms derived from B and humans (derived from A) must have survived neutral variation throughout the timespan from T to now. If the timespan is long enough, we can very safely assume that the measured homology is a measure of some specific functional information conserved from the time of the split to now.

Procedure.

I downloaded a list of the basic human proteome (in FASTA form). In particular, I downloaded it from UNIPROT selecting all human reviewed sequences, for a total of 20171 sequences. That is a good approximation of the basic human proteome as known at present.

I used NCBI’s blast tool in local form to blast the whole human proteome against known protein sequences from specific groups of organisms, using the nr (non redundant) NCBI database of protein sequences, and selecting, for each human protein, the alignment with the highest homology bitscore from that group of organisms.

Homology values:

I have used two different measures of homology for each protein alignment:

- The total bitscore from the BLAST alignment (from now on: “bits”)

- The ratio of the total bitscore to the length in aminoacids of the human protein, that I have called “bits per aminoacid” (from now on, “baa”). This is a measure of the mean “density” of functional information in that protein, which corrects for the protein length.

The values of homology in bits have a very wide range of variation in each specific comparison with a group of organisms. For example, in the comparison between human proteins and the proteins in cartilaginous fish, the range of bit homology per protein is 21.6 – 34368, with a mean of 541.4 and a median of 376 bits.

The vlaues of homology in baa , instead, are necessarily confined between 0 and about 2.2. 2.2, indeed, is (approximately) the highest homology bitscore (per aminoacid) that we get when we blast a protein against itself (total identity). I use the BLAST bitscore because it is a widely used and accepted way to measure homology and to derive probabilities from it (the E values).

So, for example, in the same human – cartilaginous fish comparison, the range of the baa values is: 0.012 – 2.126, with a mean of 0.95 and a median of 0.97 baas.

For each comparison, a small number of proteins (usually about 1-2%) did not result in any significant alignment, and were not included in the specific analysis for that comparison.

Organism categories and split times:

The analysis includes the following groups of organisms:

- Cnidaria

- Cephalopoda (as a representative sample of Mollusca, and more in general Protostomia: cephalopoda and more generally Mollusca, are, among Protostomia, a group with highest homology to deuterostomia, and therefore can be a good sample to evaluate conservation from the protostomia – deuterostomia split).

- Deuterostomia (excluding vertebrates): this includes echinoderms, hemichordates and chordates (excluding vertebrates).

- Cartilaginous fish

- Bony fish

- Amphibians

- Crocodylia, including crocodiles and alligators (as a representative sample of reptiles, excluding birds. Here again, crocodylia have usually the highest homology with human proteins among reptiles, together maybe with turtles).

- Marsupials (an infraclass of mammals representing Metatheria, a clade which split early enough from the human lineage)

- Afrotheria, including elephants and other groups (representing a group of mammals relatively distant from the human lineage, in the Eutheria clade)

There are reasons for these choices, but I will not discuss them in detail for the moment. The main purpose is always to detect the functional information (in form of homology) that was present at specific split times, and has been therefore conserved in both lines after the split. In a couple of cases (Protostomia, Reptiles), I have used a smaller group (Cephalopoda, Crocodylia) which could reasonably represent the wider group, because using very big groups of sequences (like all protostomia, for example) was too time consuming for my resources.

So what are the split times we are considering? This is a very difficult question, because split times are not well known, and very often you can get very different values for them from different sources. Moreover, I am not at all an expert of these issues.

So, the best I can do is to give here some reasonable proposal, from what I have found, but I am completely open to any suggestions to improve my judgements. In each split, humans derive from the second line:

- Cnidaria – Bilateria. Let’s say at least 555 My ago.

- Protostomia – deuterostomia. Let’s say about 530 My ago.

- Pre-vertebrate deuterostomia (including chordates like cephalocordata and Tunicates) – Vertebrates (Cartilaginous fish). Let’s say 440 My ago.

- Cartilaginous fish – Bony fish. Let’s say about 410 My ago.

- Bony fish – Tetrapods (Amphibians). Let’s say 370 My ago, more or less.

- Amphibians – Amniota (Sauropsida, Crocodylia): about 340 My ago

- Sauropsida (Crocodylia) – Synapsida (Metatheria, Marsupialia): about 310 My ago

- Metatheria – Eutheria (Afrotheria): about 150 My ago

- Atlantogenata (Afrotheria) – Boreoeutheria: probably about 100 My ago.

The simple rule is: for each split, the second member of each split is the line to humans, and the human conserved information present in the first member of each couple must have been conserved in both lines at least from the time of the split to present day.

So, for example, the human-conserved information in Cnidaria has been conserved for at least 555 MY, the human-conserved information in Crocodylia has been conserved for at least 310 My, and so on.

The problem of redundancy (repeated information).

However, there is an important problem that requires attention. Not all the information in the human proteome is unique, in the sense of “present only once”. Many sequences, especially domains, are repeated many times, in more or less similar way, in many different proteins. Let’s call this “the problem of redundancy”.

So, all the results that we obtain about homologies of the human proteome to some other organism or group of organisms should be corrected for that factor, if we want to draw conclusions about the real amount of new functional information in a transition. Of course, repeated information will inflate the apparent amount of new functional information.

Therefore, I computed a “coefficient of correction for redundancy” for each protein in the human proteome. For the moment, for the sake of simplicity, I will not go into the details of that computation, but I am ready to discuss it in depth if anyone is interested.

The interesting result is that the mean coefficient of correction is, according to my computations, 0.497. IOWs, we can say that about half of the potential information present in the human proteome can be considered unique, while about half can be considered as repeated information. This correction takes into account, for each protein in the human proteome, the number of proteins in the human proteome that have significant homologies to that protein and their mean homology.

So, when I give the results “corrected for redundancy” what I mean is that the homology values for each protein have been corrected multiplying them for the coefficient of that specific protein. Of course, in general, the results will be approximately halved.

Results

Table 1 shows the means of the values of total homology (bitscore) with human proteins in bits and in bits per aminoacid for the various groups of organisms.

| Group of organisms | Homology bitscore

(mean) |

Total homology

bitscore |

Bits per aminoacid (mean) |

| Cnidaria | 276.9 | 5465491 | 0.543 |

| Cephalopoda | 275.6 | 5324040 | 0.530 |

| Deuterostomia (non vertebrates) | 357.6 | 7041769 | 0.671 |

| Cartilaginous fish | 541.4 | 10773387 | 0.949 |

| Bony fish | 601.5 | 11853443 | 1.064 |

| Amphibians | 630.4 | 12479403 | 1.107 |

| Crocodylia | 706.2 | 13910052 | 1.217 |

| Marsupialia | 777.5 | 15515530 | 1.354 |

| Afrotheria | 936.2 | 18751656 | 1.629 |

| Maximum possible value (for identity) | 24905793 | 2.2 | |

Figure 1 shows a plot of the mean bits-per-aminoacid score in the various groups of organisms, according to the mentioned approximate times of split.

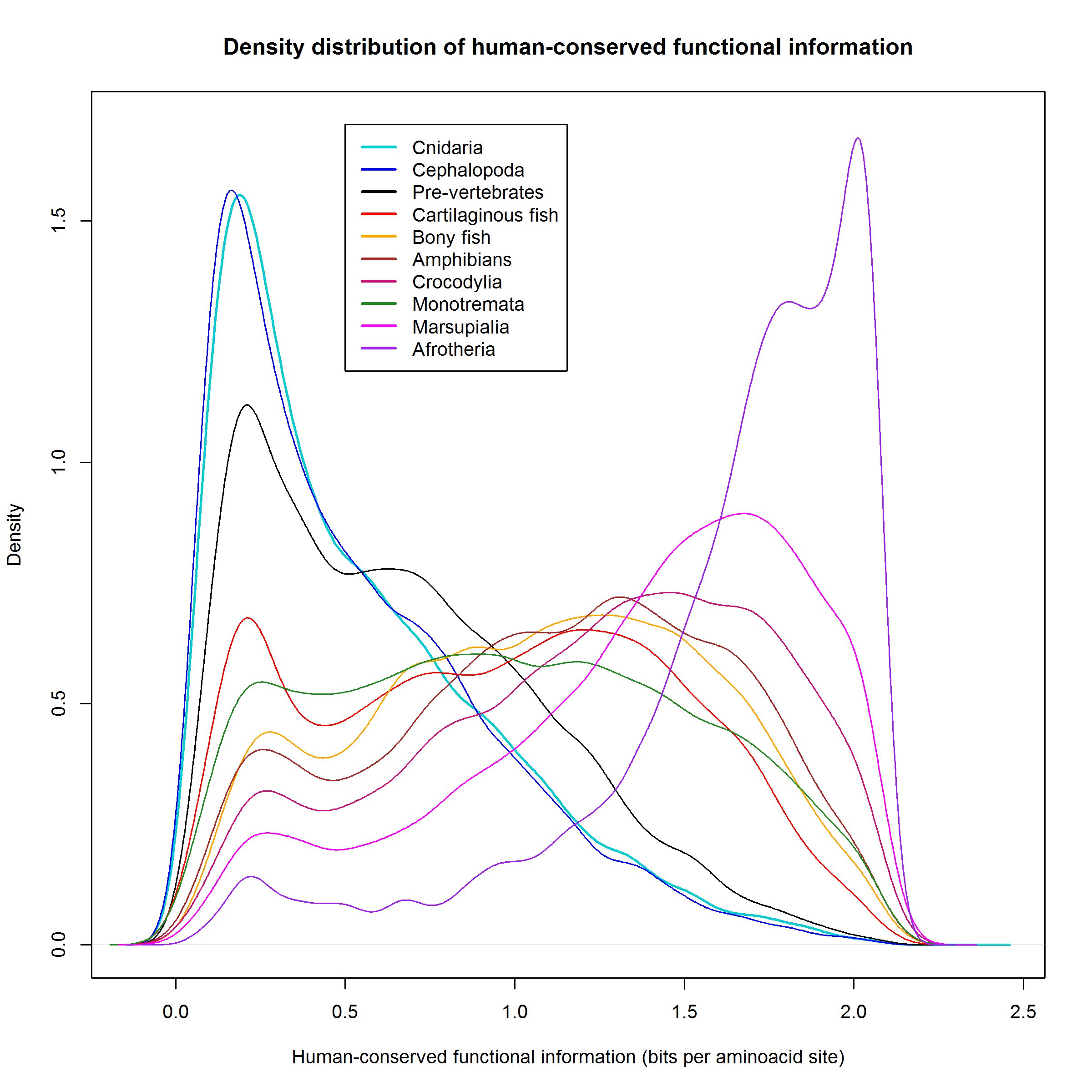

Figure 2 shows a plot of the density distribution of human-conserved functional information in the various groups of organisms.

The jump to vertebrates.

Now, let’s see how big are the informational jumps for each split, always in relation to human conserved information.

The following table sums up the size of each jump:

| Split | Homology bitscore jump (mean) | Total homology bitscore jump | Bits per aminoacid (mean) |

| Homology bits in Cnidaria | 5465491 | 0.54 | |

| Cnidaria – Bilateria (cephalopoda) | -6.3 | -121252 | -0.02 |

| Protostomia (Cephalopoda)- Deuterostomia | 87.9 | 1685550 | 0.15 |

| Deuterostomia (non vert.) – Vertebrates (Cartilaginous fish) | 189.6 | 3708977 | 0.29 |

| Cartilaginous fish-Bony fish | 54.9 | 1073964 | 0.11 |

| Bony fish-Tetrapoda (Amphibians) | 31.9 | 624344 | 0.05 |

| Amphibians-Amniota (Crocodylia) | 73.3 | 1430963 | 0.11 |

| Sauropsida (Crocodylia)-Synapsida (Marsupialia) | 80.8 | 1585361 | 0.15 |

| Metatheria (Marsupialia) – Eutheria (Afrotheria) | 162.2 | 3226932 | 0.28 |

| Total bits of homology in Afrotheria | 18751656 | 1.63 | |

| Total bits of maximum information in humans | 24905793 | 2.20 | |

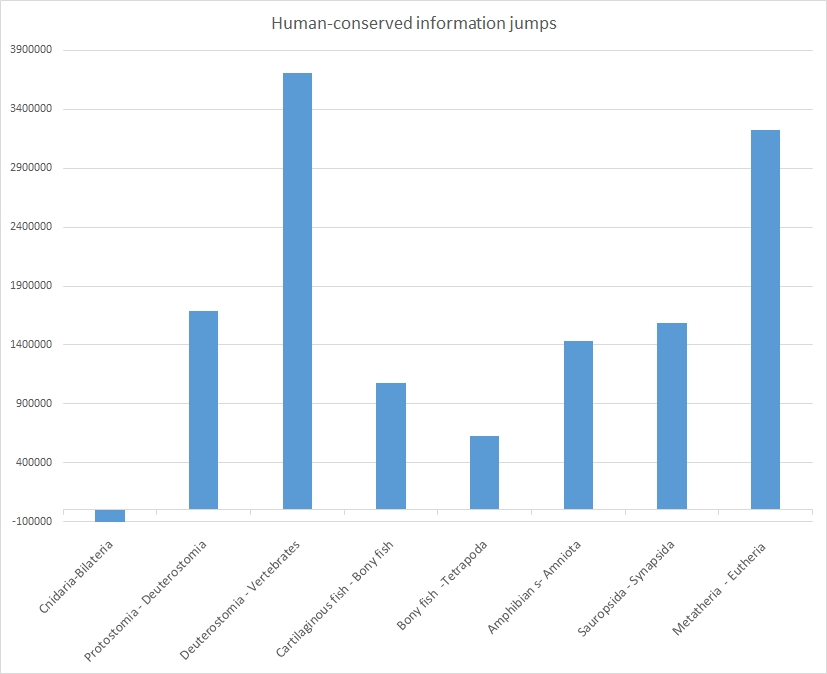

The same jumps are shown graphically in Figure 3:

As everyone can see, each of these splits, except the first one (Cnidaria-Bilateria) is characterized by a very relevant informational jumps in terms of human-conserved information. The split is in general of the order of 0.5 – 1.5 million bits.

However, two splits are characterized by a much bigger jump: the prevertebrate-vertebrate split reaches 3.7 million bits, while the Methateria-Eutheria split is very near, with 3.2 million bits.

For the moment I will discuss only the prevertebrate-vertebrate jump.

This is where a great part of the functional information present in humans seems to have been generated: 3.7 million bits, and about 0.29 bits per aminoacid of new functional information.

Let’s see that jump also in terms of information density, looking again at Figure 2, but only with the first 4 groups of organisms:

Where is the jump here?

We can see that the density distribution is almost identical for Cnidaria and Cephalopoda. Deuterostomia (non vertebrates) have a definite gain in human-conserved information, as we know, it is about 1.68 million bits, and it corresponds to the grey area (and, obviously, to the lower peak of low-homology proteins).

But the real big jump is in vertebrates (cartilaginous fish). The pink area and the lower peak in the low homology zone correspond to the amazing acquisition of about 3.7 million bits of human-conserved functional information.

That means that a significant percentage of proteins in cartilaginous fish had a high homology, higher than 1 bit per aminoacid, with the corresponding human protein. Indeed, that is true for 9574 proteins out of 19898, 48.12% of the proteome. For comparison, these high homology proteins are “only” 4459 out of 19689, 22.65% of the proteome in pre-vertebrates.

So, in the transition from pre-vertebrates to vertebrates, the following amazing events took place:

- About 3,7 million bits of human-conserved functional information were generated

- A mean increase of about 190 bits per proteins of that information took place

- The number of high human homology proteins more than doubled

Correcting for redundancy

However, we must still correct for redundancy if we want to know how much really new functional information was generated in the transition to vertebrates. As I have explained, we should expect that about half of the total information can be considered unique information.

Making the correction for each single protein, the final result is that the total number of new unique functional bits that appear for the first time in the transition to vertebrates, and are then conserved up to humans, is:

1,764,427 bits

IOWs, more than 1.7 million bits of unique new human-conserved functional information are generated in the proteome with the transition to vertebrates.

But what does 1.7 million bits really mean?

I would like to remind that we are dealing with exponential values here. A functional complexity of 1.7 million bits means a probability (in a random search) of:

1:2^1.7 million

A quite amazing number indeed!

Just remember that Dembski’s Universal Probability Bound is 500 bits, a complexity of 2^500. Our number (2^1764427) is so much bigger that the UPB seems almost a joke, in comparison.

Moreover, this huge modification in the proteome seems to be strongly constrained and definitely necessary for the new vertebrate bodily system, so much so that it is conserved for hundreds of millions of years after its appearance.

Well, that is enough for the moment. The analysis tools I have presented here can be used for many other interesting purposes, for example to compare the evolutionary history of proteins or groups of proteins. But that will probably be the object of further posts.